From The CRPG Addict

|

| Yes, I’m as surprised as you to see this screen on my blog. |

Nintendo (developer and publisher)

Glad I’m not the only one. They look . . . cute. Since when is “cute” “cool”? Aren’t things like dragons and ninjas cool? When I was a kid, I played with robots that changed into trucks. These kids play with . . . little yellow mice or something.

If I’m going to play a racing game, I want to race race cars, not goofy little go-karts piloted by mustachioed plumbers. If I’m going to pit monsters against each other in gladiatorial matches, I want them to look like monsters, not characters from the Island of Misfit Toys. And if I’m going to play an action-adventure, I want to play a classic hero, not an effete little elf with bare legs and a pointy hat.

I’m sucking up these prejudices to give The Legend of Zelda a try. Yes, we agreed several times that it’s not an RPG. But it’s RPG-ish, and its own sequel is an RPG, and had an influence on RPGs. I’ve always seen that influence as an infantilization–infantilization in character, in complexity, and in controls. But if I’m going to hold such an opinion, it ought to at least be an opinion informed by actual gameplay. At the worst, perhaps it will habituate me a bit, so if I ever deign to play your precious Chrono Trigger–which from videos looks to me like a bunch of children scurrying around–perhaps I’ll be inoculated to some of its conventions.

|

| Neither the complexity of controls nor the depiction of the “hero” fill me with interest to play this game. |

|

| I’m beginning to worry that it’s not really eight. |

As everyone but me knows until now, the Zelda games are set in a kingdom called Hyrule, ruled by Princess Zelda (reportedly named after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wife). Magic in this realm concentrates in golden triangles known as “triforces.” As the first game opens, a Prince of Darkness named Gannon has sacked Hyrule and pilfered the Triforce of Power. Zelda also had the Triforce of Wisdom, but she broke it into eight pieces and hid them around the realm to prevent its theft. Meanwhile, Zelda’s “nursemaid,” Impa, fled the castle to find someone to help. (The fact that the heroine of the title is young enough to still have a nursemaid is another strike against it.) She was rescued from Gannon’s soldiers by a “young lad” named Link, who vowed to assemble the Triforce of Wisdom and destroy Gannon.

(I gather that the name “Link” is meant to be taken somewhat literally, as in the character is the “link” between the player and the game world. As such, it’s not much different than “avatar,” although that was a title rather than a name.)

|

| The manual provides a map of most of the overworld, which helps greatly. |

Hyrule takes up 16 x 8 screens, with the character starting along the south edge in the center. On 9 of those screens are entrances to dungeons, numbered 1 to 9 in rough order of difficulty. The first eight have pieces of the Triforce, and the ninth has the confrontation with Gannon. There are also numerous entrances to caves where old men and women give hints, offer gems, and sell items. Many of these entrances (including the final dungeon entrance) are hidden and require bombs or other mechanisms to reveal.

|

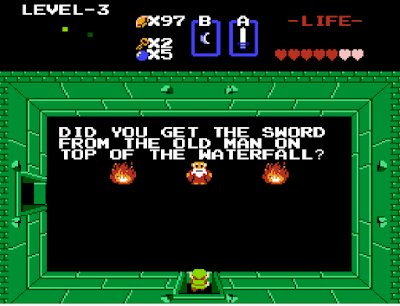

| An old man in a dungeon gives me a hint. |

On just about every screen is a collection of various enemies, the creators did an admirable job giving each enemy has its own strengths, weaknesses, and movement and attack patterns. We saw something of this in Deadly Towers, but Zelda carries it to an apex. So you have “ropes” (I had to look up the official names in the manual since they appear nowhere in the game), which are snakes who move around randomly until they get to your column or row, at which they make a sudden and swift attack directly at your character. There are “darknuts,” knight-like characters whose shields make them immune from forward attacks. “Peahats” look like chickens, and they can’t be damaged while flying; you have to wait for them to land. “Dodongos” are immune to just about everything except that they’ll eat any bombs that you leave in their path. There are at least a few dozen enemy types, and you have to learn each one.

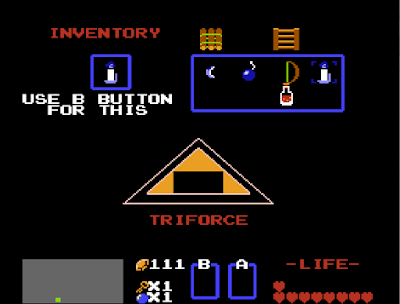

Helping you out are a variety of inventory items that Link can find and buy, starting with a wooden sword, found in the cave on the starting screen. Failure swiftly followed any player who didn’t go into that cave first. Later, you find a “white sword” and then a magical sword. Once you equip a sword, it is always activated by the “A” button, but the “B” button can cycle through a variety of other things that you can acquire, including boomerangs (regular and magic), bombs, candles, and bows and arrows. There are also artifact items used to solve particular puzzles. For instance, you need a whistle to defeat a particular enemy, a ladder to cross one-square water, and keys to open doors. Shields and rings reduce damage done to the character and potions heal it.

|

| Link gets a magic sword. Note that he has three keys, eight bombs, and eight gems. |

Life force is represented by “hearts,” of which you have a maximum of three at the beginning. As you explore, you find more “max health” hearts. I suspect there are 13 in the game (plus the original three), but I only ever found 12. Regular hearts, which heal, are dropped randomly by slain enemies, which puts Zelda in that odd genre of games in which when your health gets low, you need to head out and find something to fight.

The game does an interesting thing where when your health is at its maximum, you can fling your sword across the screen like a missile weapon–a weird idea that we seem to find in a lot of Japanese titles–but if you take any advantage, you can only swing at the square in front of you. Thus, you have a lot of incentive to keep Link at his maximum. This is pretty hard.

|

| Link’s inventory screen about halfway through. |

In fact, I was surprised at how hard the game was in general. I had originally thought to explore the world in some kind of systematic order, but that went out the window within the first few minutes, as I got my ass handed to me by enemies only two screens from the starting screen. (I particularly hate “zolas,” which live in the water and pop up every few seconds from a random location to spit a missile at you with unerring accuracy. There is no time in the game in which these things aren’t a menace.) I tend not to be good at games that require a lot of fast reaction anyway, and Zelda really put me through my paces. Earlier, I had a line that said something like, “If it’s a child’s game in content, it certainly isn’t in difficulty,” but on reflection, I suspect children are better equipped to handle the swift reactions that the game requires. It made me feel old.

Balancing the difficulty is a somewhat charitable approach to reloading. When Link “dies,” the player need only “Continue” from the starting square of the wilderness or dungeon that he’s in, with no loss of items. (In fact, saving requires you to die, then choose the “Save” option.) I “continued” to more du dungeon entrances than I cared to count. I deliberately died a lot in the outdoors just to make navigation easier, as most of the shops are more convenient to the starting area than the far-flung dungeon locations.

|

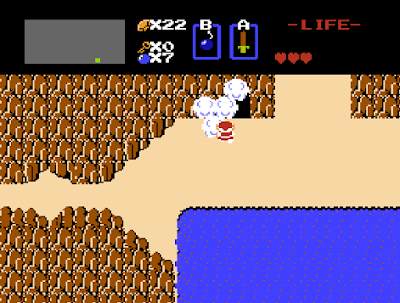

| Confronting the first dungeon boss. |

Some commenters have questioned what RPG credentials Zelda lacks, but only a few hours with the game illustrates it perfectly. The character never really gets any better, excepting increases in maximum health. But even that only prolongs death. No matter how many hearts you possess, you have to try to avoid damage as much as possible. Upgrades in weapons and armor make killing enemies faster but don’t fundamentally change the tactics that the player has to employ. Winning the game becomes possible when the player improves, not the character.

|

| One of the game’s “stores.” |

No amount of time killing low-level mooks puts Link in a better position to take on the dungeon bosses. Even “grinding” for money to buy things like potions is mostly a hopeless undertaking, since enemies drop money so slowly and rarely. I probably only bought and used five potions in the entire game. Oh, and some action games would allow the player to advance ever-so-slowly by focusing on one enemy at a time, a worthless tactic here since screens respawn.

|

| A bow is the artifact in the first dungeon. |

Another aspect of difficulty is found in simple navigation. Each dungeon is a fairly large labyrinth. Eventually, you find a compass, which shows the location of the piece of the Triforce on a little mini-map. Then you find the dungeon map, which fills in the mini-map with rooms. At some point, you find that dungeon’s artifact item–I think each one has one–and the whole thing is capped with the dungeon boss and then the piece of the Triforce. Picking up the Triforce piece restores all your health and warps you out of the dungeon.

But getting through all of the dungeon rooms is a huge pain. If you don’t find keys in the right order, you could end up facing a locked door with no way through it. Some navigation requires planting bombs against the walls and blowing open secret holes. (You can only carry a maximum of eight bombs at a time, and these go fast, so I was constantly running around, in and out of the dungeons, looking for enemies that dropped bombs.) Other times, you have to push blocks on the floor to reveal secret stairways. Sometimes, you have to kill every enemy in a room before a door will open or a key will drop.

|

| Typical dungeon room swarming with various enemies. One I kill them all, I’ll have to push the west block out of the way to reach the stairway. |

In the outdoors, it’s almost as bad. You also need bombs there to explore caves, but they’re much more sensitive to specific locations, and you can easily miss the secret entrance if you’re a pixel off. Basically, you have to bomb every inch of cliff face to make sure you’re not missing anything. Trees disguise other entrances, but they can’t be bombed. You have to toss a candle on them–a process that works only once per screen until you find the “red candle” late in the game. So to make sure you haven’t missed anything, you have to run on and off the screen multiple times, testing the candle on each tree. Some screens have dozens of trees.

|

| Blowing up a wall to find a secret cave. |

To be fair, there are hints in the manual and throughout the game that help with this process, but I never found any hint that would have led me to the secret entrance to Death Mountain, the final dungeon, nor to many of the in-dungeon secret areas, and especially not to the dungeon entrance where I had to blow a whistle to drain a lake. Then again, I don’t think Zelda was meant to be a 12-hour game. I think it was meant to be a 120-hour game in which the player was meant to explore every inch of every screen, to become so familiar with the landscape that he could have thrown away the map that came with the game, and to trade findings with friends. There are RPGs that require such investments of time, too, but at least you’re earning levels and experience points in those.

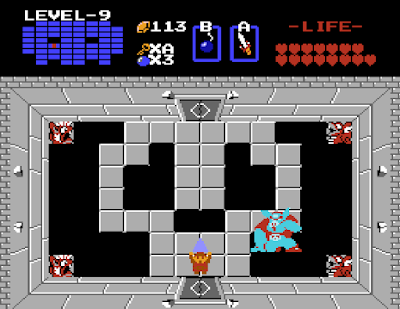

If you sort it all out, you make it through the final dungeon and confront Gannon in a room where unkillable things in the corner shoot fireballs at you. He turns invisible after the first hit, but you can kind of figure out where he is from where his missiles are coming from. You keep running around, attacking, throwing bombs, whatever, until he turns brown, at which point you have to shoot him with a silver arrow (there’s a hint to this somewhere), at which point he explodes and drops the Triforce of Power. The final screens show Link presenting the Triforce to Princess Zelda, and the two kids present their respective Triforces while a text screen talks about peace returning to Hyrule.

|

| Gannon is apparently some kind of ape with a Mercedes hood ornament for a belt buckle. |

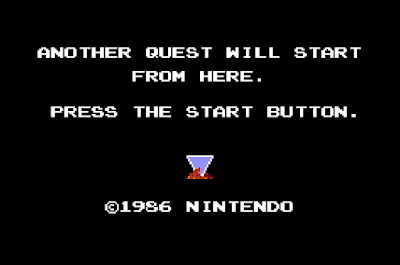

And then something terrifying happens. The screen says: “Another quest will start from here.” You’re dumped back onto the game map with three hearts, no equipment, and apparently a second mandate to find the pieces of the Triforce and to defeat Gannon, only with the maps changed and items in different locations. I trust a player doesn’t have to complete both quests to have “won” the game.

|

| No! What kind of reward is this?! |

In any event, I was less interested in “winning” Zelda than experiencing and documenting it. I have to confess to some cheating. Nestopia is about the easiest emulator in the world for save states, requiring you to only hit SHIFT and a number to save, and then just the number to reload. I used these gingerly at first, much more liberally towards the end. I particularly remember one room with three dodongos in which I had six bombs–exactly enough to kill them if none was wasted. I saved after every successful bomb. I also looked up locations of secret areas when I got stuck. The final battle with Gannon took me so many tries that I was motivated to look up an invincibility cheat code, and found one, but I couldn’t get it to work, so I defeated him with just regular save-state cheating.

Nonetheless, I got the experience I was looking for, which was mostly negative. I admit there is a natural addictive property with just about every action game. If RPGs pull you along for “just one more screen” with the promise of the next upgrade, action games have a way of propelling you from screen to screen with sheer momentum.

I also like the idea of the occasional “boss enemy” who fights by his own rules and requires the player to discern patterns and test tactics to defeat him. These are common even in RPGs today, but in the 1980s and early 1990s, developers were too concerned with consistency and following an established monster manual. You never meet a formidable warrior with 200 hit points in a Gold Box game who shoots lighting from his swords because there are rules about “hit dice” and there are no Swords of Lightning.

|

| A dragon with multiple heads serves as a dungeon boss. |

But overall, Zelda still represents to me a malevolent influence on RPGs: reduction of tactics to a couple of buttons, the kawaii character style, character development via found items rather than earned ones, limited inventories and economies, and ridiculous swarms of floating, flying, spitting, belching enemies on every screen. I’d be more upset about it, but it’s not like people stopped making more traditional RPGs. Heck, even if I limited my list to games that I actively wanted to play, I doubt I’d be much further than 1996 by now. The point is, there are plenty of games for everyone’s tastes.

|

| This doesn’t come anywhere close to ending the story. |

And Zelda was clearly to a lot of players’ tastes. As with Final Fantasy, I’m not sure it’s possible to pin an actual number on the titles in the series, what with all the sequels, spinoffs, expansions, and remakes. The series doesn’t show any signs of ending, even in 35 years later. There have been cartoons, comics, albums, a television series . . . a freaking cereal. Why doesn’t The Witcher have a cereal?

I remain mystified. In their best depictions, Princess Zelda and Link look like pre-teens, and their best games (I based this on reading descriptions of the major sequels), they approach the level of complexity that you find a good RPG. I don’t quite understand what motivates people, let alone full-grown adults, to want to play these titles.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/game-353-legend-of-zelda-1986.html