In one of the last interviews he gave before his death, shareware pioneer Jim Button said that he “had written off the idea of shareware games” prior to the beginning of the 1990s. At the time, it seemed a reasonable position to take, one based on quite a bit of evidence. While any number of people had tried to sell their games this way, there had been no shareware success stories in games to rival those of Andrew Fluegelman, Jim Button, or Bob Wallace.

Naturally, many pondered why this should be so. The answers they came up with were often shot through with the prejudices of the period, which held that programming or playing frivolous games was a less upstanding endeavor than that of making or using stolid business software. Still, even the prejudiced answers often had a ring of truth. You had a long-term relationship with your telecommunications program, database, or word processor, such that sending its author a check in order to join the mailing list, acquire a printed manual, and be assured of access to updates felt as much like a wise investment as merely “the honest thing to do.” But you had a more transient relationship with games; you played a game only until you beat it or got tired of it, then moved on to the next one. Updates and other forms of long-term support just weren’t a factor at all. No one could seem to figure out how to untangle this knot of motivation and contingency and make shareware work for games.

Luckily, there was an alternative to the shareware model for those game programmers who lacked the right combination of connections, ambitions, and talents to go the traditional commercial route — an alternative that offered a better prospect than shareware during the 1980s of getting paid at least a little something for one’s efforts. It was the odd little ghetto of the disk magazines, and so it’s there that we must start our story today.

The core idea behind the disk magazines is almost as old as personal computing itself. In February of 1978, Ralph McElroy of Goleta, California, published the first issue of CLOAD, a monthly collection of software for the Radio Shack TRS-80, the first pre-assembled microcomputer to rack up really impressive sales numbers. “To join the somewhat elite club of computer users,” wrote McElroy in his introductory editorial, “one [previously] had to learn the mysterious art of speaking in a rather obscure tongue” — i.e., one had to learn to program. Before any commercial software industry to speak of existed, CLOAD proposed to change that by offering “vast quantities of software to be shared.” It was actually distributed on cassette tape rather than floppy disk — a disk drive was still a very exotic piece of hardware in 1978 — but otherwise it put all the pieces into place.

By 1981, the TRS-80’s early momentum was beginning to flag and the more capable Apple II was coming on strong. Jim Mangham, a programmer at the Louisiana State University Medical Center in Shreveport, decided that the market was ready for a CLOAD equivalent for the Apple II — albeit published not on cassettes but on floppy disks, which were now steadily gaining traction. He recruited a buddy named Al Vekovius to join him in the venture, and the two prepared the first issue of something they called The Harbinger. They called up Softalk magazine, the journal of record for early Apple II users, to discuss placing an advertisement, whereupon said magazine’s founder and editor Al Tommervik got so excited by their project that he asked to become an investor and official marketing partner. Thus The Harbinger acquired the rather less highfalutin name of Softdisk to connote its link with the print magazine.

Starting with just 50 subscribers, Mangham and Vekovius built Softdisk into a real force in Apple II computing. Well aware that they couldn’t possibly write enough software themselves to fill a disk every single month, they worked hard from the beginning to foster a symbiotic relationship with their readership; most of the programs they published came from the readers themselves. In the early days, the spirit of reciprocity extended to the point of expecting readers to mail their disks back each month; this both allowed Mangham and Vekovius to save money on media and provided a handy way for readers to send in their programs and comments. Even after this practice was abandoned in the wake of falling disk prices, Softdisk subscribers felt themselves to be part of a real digital community, long before the rise of modern social media made such things par for the course. At a time when telecommunications was a slow, difficult, complicated endeavor, Softdisk provided an alternative way of feeling connected with a larger community of people who were as passionate as oneself about a hobby which one’s physical neighbors might still regard as hopelessly esoteric.

Thus Mangham and Vekovius’s little company Softdisk Publishing slowly turned into a veritable disk-magazine empire. In time, Mangham stepped back from day-to-day operations, becoming a nearly silent partner to Vekovius, always the more business-focused of the pair. He expanded Softdisk to two disks per issue in August of 1983; started reaching retail stores by January of 1984; launched a companion disk magazine called Loadstar for the Commodore 64 in June of 1984. Softdisk survived the great home-computer bust of the second half of 1984, which took down Softalk among many other pioneering contemporaries, then got right back to expanding. In November of 1986, Vekovius launched a third disk magazine by the name of Big Blue Disk, for MS-DOS-based computers; it soon had a monthly circulation of 15,000, comparable to that of Softdisk and Loadstar. A fourth disk magazine, for the Apple Macintosh this time, followed in 1988. At least a dozen competitors sprang up at one time or another with their own disk magazines, but none seriously challenged the cross-platform supremacy of the Softdisk lineup.

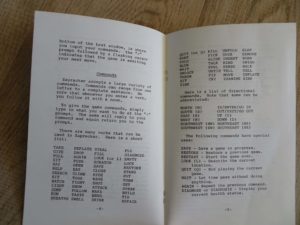

In order to encourage software submissions, all of the Softdisk magazines ran a periodic programming competition called CodeQuest. Readers were encouraged to send in programs of any type, competing for prizes of $1000 for the top submission, $500 for second place, and $250 for third place, on top of the money Softdisk would pay upon eventually publishing the winning software. Big Blue Disk‘s second incarnation of the contest ended on January 31, 1988, yielding two winners that were fairly typical disk-magazine fare: the gold-winning The Compleat Filer was a file-management program to replace the notoriously unfriendly MS-DOS command line, while the bronze-winning Western was a sort of rudimentary text-based CRPG set in, you guessed it, the Old West. But it was the silver winner — a game called Kingdom of Kroz, submitted by one Scott Miller from a suburb of Dallas, Texas — that interests us today.

At the time of the contest, Miller didn’t seem to be going much of anywhere in life. In his late twenties, he was still attending junior college in a rather desultory fashion whilst working dead-end gigs at the lower end of the data-processing totem pole, such as babysitting his college’s computer lab. His acquaintances hardly expected him to ever move out of his parents’ house, much less change an industry. Yet this seeming slacker had reserves of ambition, persistence, marketing acumen, and sheer dogged self-belief that would in the end prove a stick in the eye to every one of his doubters. Scott Miller, you see, wanted to make money from videogames — make a lot of money. And by God, he was going to find a way to do it.

Before entering the CodeQuest contest, he’d written a column on games for the local newspaper, written a book on how to beat popular arcade games, and, last but not least, tested the early shareware market for games: he’d written and distributed a couple of shareware text adventures under the name of Apogee Software — a name which would later become very, very famous among a certain segment of gamers. But on this occasion he was disappointed by the response, just like everyone else making shareware games at the time. Unlike most of those others, though, Miller didn’t give up. If shareware text adventures wouldn’t do the trick, he’d just try something else.

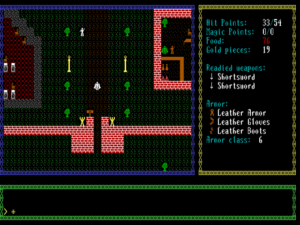

Put crudely, Kingdom of Kroz was a mash-up of the old mainframe classic Rogue and the arcade game Gauntlet — or, if you like, a version of Rogue that played in real time and had handcrafted levels instead of procedurally-generated ones. It wasn’t much to look at — like classic Rogue, it was rendered entirely in ASCII graphics — but many people found it surprisingly addictive once they got into it. It went over very well indeed with Big Blue Disk‘s subscribers when it appeared in the issue dated June 1988 — went over so well that Miller provided two sequels, called Dungeons of Kroz and Caverns of Kroz, almost immediately, although the magazine wouldn’t find an opening for them in its editorial calendar until the issues dated March and September of 1989.

While he waited on Big Blue Disk to release those sequels, Miller started to explore a new idea for marketing games outside the traditional publishing framework. In fact, this latest idea would eventually prove his greatest single stroke of marketing genius, even if its full importance would take some time yet to crystallize. He would later sum up his insight in an interview: “People aren’t willing to pay for something they’ve already got in their hands, but they are willing to pay if it gets them something new.” Call it a cynical notion if you must, but, in the context of games at least, it would prove the only way to make shareware pay on a scale commensurate with Scott Miller’s ambitions.

Miller and George Broussard, his longtime best friend and occasional partner in the treacherous world of shareware, made an engine for multiple-choice trivia games — not exactly a daunting programming challenge after the likes of Kroz. They compiled sets of questions dealing with different topics: general trivia, vocabulary, the original Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation. They created “volumes” in each category consisting of 100 questions. Then they released the first volume of each category online, accompanied by an advertisement for additional volumes for the low, low price of $4 each.

Alas, the scheme proved not to be a surefire means of selling trivia games; the economics of getting just 100 questions for $4 were perhaps a bit dodgy even in the late 1980s, when just about everything involving computers cost exponentially more than it does today. But a seed had been planted; the next time Miller tried something similar, he would finally hit pay dirt.

The next time in question came in the second half of 1989, just after Big Blue Disk published the last Kroz game. The magazine’s contract terms were far more generous than those of any traditional software publisher: Miller had retained the Kroz copyright throughout, and the magazine’s license to it became non-exclusive as soon as it published the third and last game of the trilogy. Miller, in other words, could now do whatever he wished with his three Kroz games, while still benefiting from the buzz their appearance in Big Blue Disk had caused in some quarters.

So, he decided to try the same scheme he had used with his trivia games: release the first part of the trilogy for free, but ask people to send him $7.50 each for the second and third parts. A tactic that had prompted an underwhelming response the first time around worked out much better this time. Unlike those earlier exercises in multiple choice, the Kroz trilogy was made up of real games — or, perhaps better said, was actually one real game artificially divided into three. After you’d played the first part of said game, you wanted to see the rest of it through.

In short, Scott Miller — and shareware gaming in general — finally got their equivalent to that day when Jim Button returned home from a Hawaiian vacation to find his basement drowning in paid registrations. Suddenly Miller as well was drowning in mail, making thousands of dollars every month. He’d done it; his dogged persistence had paid off. He’d found a way around the machinations of the big publishers, found a way to sell games on his own terms, cracked the code of shareware gaming. His sense of vindication after so many years of struggle must defy description.

From here, things happened very, very quickly. Miller whipped up a second trilogy of Kroz games to sell under the same model — first part free, second and third must be paid for — and was rewarded with more checks in the mail. Most people at this point would have been content to continue writing lone-wolf games and reaping huge rewards — but Miller was, as I’ve already noted, a man of unusual ambition. At heart, he was more passionate about marketing games than programming them; in fact, he would never program another game at all after the second Kroz trilogy.

Already before 1989 was over, he had reached out to a Silicon Valley youth named Todd Raplogle, who had created and uploaded to various bulletin-board systems a little action-adventure called Caves of Thor that was similar in spirit to the Kroz games. Miller convinced Raplogle to re-release his free game under the Apogee imprint, and to make two paid sequels to accompany it. Raplogle followed that trilogy up with a tetralogy called Monuments of Mars. Meanwhile George Broussard returned on the scene to make two more four-volume series, called Pharaoh’s Tomb and Arctic Adventure.

By 1991, Apogee was off and running as a real business. Miller quit his dead-end day jobs, moved out of his parents’ house, convinced Broussard to join him as a full-time partner, found an accountant, leased himself an office, and started hiring helpline attendants and clerical help to deal with a workload that was mushrooming for all the right reasons. His life had undergone a head-spinning transformation in the span of less than two years.

At this point, then, we might want to ask ourselves in a more holistic way just why Apogee became so successful so quickly. Undoubtedly, a huge part of the equation is indeed the much-vaunted “Apogee model” of selling shareware: hook them with a free game, then reel them in with the paid sequels. Yet that wasn’t a silver bullet in and of itself, as Miller’s own early lack of success with his trivia games illustrates. It had to be executed just right — which tells us that Miller got it just right the second time around. The price of $7.50 was enough to make the games extremely profitable for Apogee in relation to the negligible amounts of money it took to create and market them, but cheap enough that customers could take the plunge without feeling guilty about it or needing to justify it to a significant other. Likewise, each game was perfectly calibrated to be just long enough for the customer not to feel cheated, but not so long that she spent hours playing it which she could have sunk into another Apogee game.

If all of this sounds a bit mercenary, so be it; Miller was as hard-nosed as capitalists come, and he certainly wasn’t running Apogee as a charity. Yet it’s seldom good business, at least in the long run, to sell junk, and this too Miller understood. Apogee maintained a level of quality control that was often lacking even from the big publishers, who often felt compelled to release a game before its time to meet the Christmas market or to pump up the quarterly numbers. Apogee games, on the other hand, seldom appeared under a Christmas tree, and Miller had no shareholders other than his best friend to placate. “Our philosophy is never to let an arbitrary date dictate when we release a game,” said Miller in an interview. As a result, their games were small but also tight: bug-free, stable, consistent. They evinced a sense of care, felt like creations worth paying a little something for. Soon enough, people learned that they could trust Apogee. If none of Apogee’s early games were revolutionary advances within the medium, there were few to no complete turkeys among them either.

I’ll be the first to admit that the Apogee style of game does little for me. Still, my personal tastes in no way blind me to the reality that these unprepossessing but well-crafted little games filled a space in the market of the early 1990s that the big publishers were missing entirely as they rushed to cement a grand merger of Silicon Valley and Hollywood and begin the era of the “interactive movie.” While the boxed-games industry went more and more high-concept, with prices and system requirements to match, Apogee kept things simple and fun, as befit their slogan: “Apogee means action!” Apogee games were quick to play, quick to get in and out of; they had some of the same appeal that the earliest arcade games had, albeit implemented in a more user-friendly way, with the addictive addition of a sense of progression through their levels. The traditional industry regarded this sort of thing as hopelessly passé on a personal computer, suitable only for videogame consoles like the Nintendo Entertainment System. But, as the extraordinary success of Nintendo and the only slightly less extraordinary success of Apogee both demonstrated, people still wanted these sorts of games. Their near-complete absence from the boxed-computer-game market left a massive hole which Scott Miller was happy to fill. Younger people with limited disposal income found Apogee particularly appealing; they could buy six or seven Apogee games for the price of one boxed production that would probably just bore them anyhow.

But of course a business model as profitable as Miller’s must soon attract rivals who hope to execute it even better. Already in 1992, a company called Epic MegaGames appeared to challenge Apogee for the title of King of Shareware; they as well employed Scott Miller’s episodic approach, and also echoed Apogee’s proven action-first design aesthetic. Shareware gaming was becoming a thriving shadow industry of its own, right under the noses of the big boys who were still chasing after their grand cinematic fantasias. They would have gotten the shock of their lives if they had ever bothered to compare their slim profit margins to the fat ones of Apogee and Epic. As it was, though, they felt nary an inkling in their ivory towers that a proletarian revolution in ludic aesthetics was in the offing out there on the streets. But even they wouldn’t be able to ignore it for much longer.

This shareware sales chart from July of 1993 shows how dominant Apogee was at that time. Seven out of the top ten games are theirs, with a further two going to Epic MegaGames, their only remotely close competitor. Although the fast-and-simple design aesthetic in which those companies specialized ruled the charts, they pulled with them a long tale of many other types of shareware games, as we’ll see in the next part of this article. The very fact that there existed a sales chart like this one at all says much about how quickly shareware had exploded in a very short time.

Many of you doubtless have an inkling already of where this series of articles must go from here — of how not only the story of Apogee Software but also that of Softdisk Publications will feed directly into that of the most transformative computer game in history. And never fear, I’ll get to all of that — but in my next article rather than this one.

For in addition to that other story which threatens to suck all the oxygen out of the room, there are a thousand other, smaller ones of individual creators being inspired to program all kinds of games and sell them as shareware in the wake of Apogee’s success. Exactly none of them made as much money from their endeavors as did Scott Miller, but some became popular enough to still be remembered today. Indeed, many of us who were around back then still have our obscure little hobby horses from the shareware era that we like to take out and ride from time to time. My personal favorite of the breed might just be Pyro II, a thunderously non-politically-correct puzzle game in which you play a pyromaniac who must burn down famous buildings all over the world. Truly, though, the list of old shareware games that come up in any given discussion is guaranteed to be almost as long as the list of old-timers reminiscing about them. The shareware gaming scene in the aggregate which took off after Apogee’s success touched a lot of people’s lives, regardless of how much money this or that individual game might have earned.

Like the Apogee games, many other shareware titles identified holes in the market which the big publishers, who all seemed to be rushing hell-bent in the exact same direction, were failing to fill. In many cases, these were genres from which the traditional industry had actually done very well in the past, but which which it had now judged to no longer to be worth its while. For example, the years between the collapse of Infocom in 1989 and the beginning of the Internet-based Interactive Fiction Renaissance circa 1995 were marked by quite a number of shareware text adventures. Likewise, as boxed CRPGs got ever more plot- and multimedia-heavy at the expense of the older spirit of free-form exploration, other shareware programmers rushed to fill that gap. Still others mimicked the look and feel of the old ICOM Simulations graphic adventures, while lots more catered to the eternal need just to blow some stuff up after a long, hard day. There were shareware card games, board games, strategy games, fighting games, action puzzlers, proto-first-person shooters of various stripes, and some concoctions that defy description.

In terms of presentation, most of these shareware games were dead ringers for the games that had been sold on store shelves five to ten years earlier. And by the same token, the people who made them in the 1990s were really not all that different from the bedroom programmers who had built the boxed-games industry in the 1980s. Just as many creators of non-game shareware were uncomfortable with time-limited or otherwise crippled software, not all creators of shareware games embraced the Apogee model — not even after it had so undeniably demonstrated its efficacy. Even then, some idealistic souls were still willing to place their faith in people sending in checks simply because it was the right thing to do. All of which is to say that shareware gaming encompassed a vast swath of motivations, styles, and approaches. Apogee, Epic, and that other company which we’ll get to in my next article tend to garner all the press when the early 1990s shareware scene is remembered today, but they were by no means the sum total of its personality.

By way of illustration, I’d like to conclude this article with a short case study of a shareware parnership that didn’t make its principals rich, that didn’t even allow them to quit their day jobs. In fact, neither partner ever really even tried to achieve either of those things. They just made games in two unfashionable styles which they still happened to love, and said games made some other people with the same tastes very happy. And that was more than enough for Daniel Berke and Matthew Engle.

Matthew remembers his best childhood Christmas ever as the one in 1983, when he was twelve years old and his family got an Apple IIe computer. A sheet of Apple-logo stickers came in the box that housed the computer, and Matthew stuck one of them on his notebook. Soon Daniel, another student at his Los Angeles-area school, noticed the sticker and came over to chat. “I’ve got an Apple II also!” he said. Just like that, a lifelong friendship was born.

The two joined an informal community of fellow travelers, the likes of which could be found in school cafeterias and playgrounds all over the country, swapping tips and exploits and most of all games. Their favorites of the games they traded were the text adventures of Infocom and the Ultima CRPGs of Origin Systems; if the pair’s friendship was born over the Apple II, it was cemented during the many hours they spent plumbing the depths of Zork together. Matthew and Daniel eventually joined the minority of kids like them who took the next step beyond playing and trading games: they started to experiment with making them. Their roles broke down into a classic game-development partnership: the analytical Daniel took to programming like a duck takes to water, while the more artistically-minded Matthew was adept at drawing and storytelling.

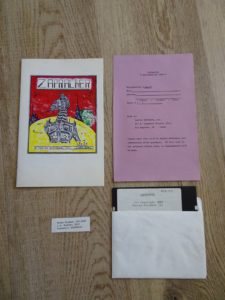

So many things in life are a question of timing — not least the careers of game developers. One story which Matthew Engle shared with me when I interviewed him in preparation for this article makes that point disarmingly explicit. In 1986, Daniel, Matthew, and another friend created a BASIC text adventure called Zapracker, which they attempted to sell through their local software stores. Matthew:

We made our own boxes and packaged the game with the floppy disk and the manual, just like Richard Garriott did back in the day. Our box was designed to hang on a peg in a software store. We got on a bus with 25 or so copies and visited a few different stores. We’d say, “Hey, would you like to sell this on consignment? You get half the money and we get half.” A few stores took us up on it, and we sold a few copies.

Zapracker (A Lost Classic?)

This tale is indeed almost eerily similar of that of Richard Garriott selling a Ziploc-bagged Akalabeth through his local Computerland just six years earlier; if anything, our heroes in 1986 would appear to have put more effort into their packaging, and perhaps into their game as well, than Garriott did into his. But in the short span of barely half a decade, the possibility of parlaying a homemade game hanging on a rack in a local computer store into an iconic franchise had evaporated. Instead Daniel and Matthew would have to go another route.

Their game-making efforts were growing steadily more sophisticated, as evinced by Daniel’s choice of programming languages: after starting off in Apple II BASIC, he moved on to an MS-DOS C compiler. Adopting unknowingly the approach that had already been used by everyone from Scott Adams to Infocom, from Telarium to Polarware to Magnetic Scrolls, Daniel wrote an interpreter in C which could present a text adventure written in a domain-specific language of his own devising. Matthew then wrote most of the text for what became Skyland’s Star, a science-fiction scenario.

During the pair’s last year in high school, the Los Angeles school district and the manufacturing conglomerate Rockwell International co-sponsored a contest for interesting student projects in computer science. Once Daniel and Matthew decided to enter it, it gave them a thing which many creators find invaluable: a deadline. They finished up their game, and submitted it alongside the technological framework that enabled it. They were soon informed that their project was among the finalists, and were invited to a dinner and awards ceremony at a fancy hotel. Matthew:

All of the finalists were there, demonstrating their entries. We did a couple of interviews for a local TV station. Then the dinner started. They started running down the list of winners, and before we knew it, it was down to two finalists: my and Dan’s project and another one. Then they announced the other one as second place; we had won. It was quite a night!

Matthew Engle and Daniel Berke win the contest with Skyland’s Star in 1989. That’s Daniel’s Apple II GS running the game; he wrote it on that machine in MS-DOS via a PC Transporter emulator card.

Daniel and Matthew gave little initial thought to monetizing their big win. After finishing high school in 1989, they went their separate ways, at least in terms of physical location: Daniel moved to New York to study computer science, while Matthew stayed in Los Angeles to study film. But they kept in touch, and soon started talking about making another game, this time in the spirit of their other favorite type from the 1980s: an old-school Ultima.

It was 1991 by now, and, fed by the meteoric success of Apogee, shareware games of many different stripes were appearing. Daniel and Matthew as well finally caught the fever. They belatedly released Skyland’s Star as shareware for $15, using it as a sort of test case for the eventual marketing of their Ultima-alike. They were among those noble or naïve souls who eschewed the Apogee model in favor of releasing their whole game at once. Instead of offering the rest of the game as an enticement, Daniel and Matthew offered a printed instruction manual, hint book, and map — nice things to have, to be sure, but perhaps not things that played on the psychological compulsions of gamers so powerfully as the literal rest of a game which they dearly wanted to finish. Daniel and Matthew weren’t overwhelmed with registrations.

Progress on the Ultima-like game, which was to be called Excelsior Phase I: Lysandia, was inevitably slowed by their respective university studies; the biggest chunk of the work got done in the summers of 1991, 1992, and 1993, when Daniel came back to Los Angeles and they both had more free time. Then they would sit for hours many days at their favorite pizza restaurant, sketching out their plans. Matthew did most of the scenario design, graphics, and writing, while Daniel did all of the programming.

Calling themselves by now 11th Dimension Entertainment, they finished and released Excelsior in 1993 as shareware, with a registration price of $20. Once again, they relied on a manual, a hint book, and a map alongside players’ consciences to convince them to register. Although it certainly didn’t become an Apogee-sized success story, Excelsior did garner more attention and registrations than had Skyland’s Star. It was helped not only by its being in a (marginally) more commercially viable genre, but also by its coming into a world that was just on the cusp of the Internet Revolution, with the additional distribution possibilities which that massive change to the way that everyday people used their computers brought with it.

As they were finishing Excelsior, Daniel and Matthew had also been finishing their degree programs. Daniel got a programming job at Electronic Arts after a few false starts, while Matthew started a career in Hollywood that would put him, ironically given the retro nature of Excelsior, on teams making cutting-edge CD-ROM-enabled multimedia products at companies like Disney Interactive. Despite their busy lives, they were both still excited enough by independent game development, and gratified enough by the response to Excelsior I, that they embarked on a sequel in 1994. Whereas Excelsior I had aimed for a point somewhere between Ultima IV and Ultima V, Excelsior II took Ultima VI as its model, with all of the increased graphics sophistication that would imply. For this reason not least, the partners wound up spending fully five years making it, communicating almost entirely electronically.

The sheer quantity of labor which Matthew in particular put into this retro-game with limited commercial prospects could have been motivated only by love. Matthew:

We went all out. I ultimately made about 3800 16 X 16-pixel tiles. It was an exhausting process. For every tile, I had to specify whether you could walk on it or it would block you. There was also transparency; we had layers of tiles, overlaid upon one another. There might be a grass tile, then the player-character tile. Then, if you’re walking through a doorway, for example, the arch at the top of the doorway.

Then, after that exhausting process, began the arduous process of putting the tiles down to create the map, which was 500 X 500 tiles if I’m not mistaken — so, 250,000 tiles to place. Plus all of the town and castle and dungeon maps had to be created.

By the time they released Excelsior Phase II: Errondor in 1999, software distribution had changed dramatically from what it had been six years before. It was now feasible to accept credit-card registrations online, and to offer registrants the instant satisfaction of downloadable PDF documents and the like. The motivating ethic of the original shareware movement was alive and well in its way, but, just as with other types of software, the phrase “shareware games” was soon to fall out of use. The more tactile, personal side of the shareware experience, entailing mailed checks, documents, and disks, had already mostly faded into history. Excelsior II did reasonably well for a niche product in this brave new world, but even before its release Daniel and Matthew knew that it would be their last game together. “We realized we just didn’t have it in us to do an Excelsior III,” says Matthew.

In the end, the two of them sold roughly 500 copies each of Excelsior I and II — “small potatoes” by any standard, as Matthew freely admits. He believes that they made perhaps $5000 to $10,000 in all on their games, after the cost of postage and all those printed manuals was subtracted.

I must confess that I personally have some reservations about the 11th Dimension games. It seems to me that Skyland’s Star‘s scenario isn’t quite compelling enough to overcome the engine’s limited parser and lack of player conveniences, and that the Excelsior games, while certainly expansive and carefully put-together, rely a bit too much on needle-in-the-haystack hunting over their enormous maps. Then again, though, I have the exact same complaints about the Ultima games which Excelsior emulates, which would seem to indicate that Daniel and Matthew actually achieved their goal of bringing old-school Ultima back to life. If you happen to like those Ultima games a little more than I do, in other words, you’ll probably be able to say the same about the Excelsior games. One thing that cannot be denied is that all of the 11th Dimension games reflect the belief on the part of their makers that anything worth doing at all is worth doing well.

Shareware gave a place for games like those of Daniel and Matthew to live and breathe when the only other viable mode of distribution was through the boxed publishers, who interested themselves only in a fairly small subset of the things that games can do and be. Long before the likes of Steam, the shareware scene was the indie-games scene of its time, demonstrating all of the quirky spirit which that phrase has come to imply. While the big boys were all gazing fixedly at the same few points in the middle distance, shareware makers dared to look in other directions — even, as in the case of Daniel and Matthew, to look behind them. In the face of a mainstream industry which seemed hell-bent on forgetting its history, that was perhaps the most radically indie notion of them all.

(Sources: the books Masters of Doom by David Kushner, Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Age of First-Person Shooters by David L. Craddock, and Sophistication & Simplicity: The Life and Times of the Apple II Computer by Steven Weyhrich; Computer Gaming World of December 1992, January 1993, March 1993, May 1993, June 1993, July 1993, September 1993, January 1994, February 1994, and June 1994; Game Developer of January/February 1995; PC Powerplay of May 1996; Questbusters of November 1991; Los Angeles Times of February 6 1987; the tape magazine CLOAD of February 1978; the disk magazine Big Blue Disk of January 1988, May 1988, June 1988, March 1989, April 1989, September 1989, and August 1990. Online sources include the archives on the old 3D Realms site, the M & R Technologies interview with Jim Knopf, Samuel Stoddard’s Apogee FAQ, Al Vekovius’s old faculty page at Louisiana State University Shreveport, Stephen Vekovius’s appearance on All Y’all podcast, “Apogee: Where Wolfenstein Got Its Start” at Polygon, Benj Edwards’s interview with Scott Miller for Gamasutra, and Matt Barton’s interview with Scott Miller. Most of all, I owe a warm thank you to Matthew Engle for giving me free registered copies of the 11th Dimension games and talking to me at length about his experiences in shareware games.

In the interest of full disclosure as well as a full listing of sources, I have to note that a small part of this article is drawn from lived personal experience. I actually knew Scott Miller and George Broussard in the late 1980s and early 1990s, albeit only in a very attenuated, second-hand sort of way: Scott dated my sister for several years. Scott and George came by my room from time to time to see the latest Amiga games when I was still in high school. Had I known that my sister’s lovelife had provided my with a front-row seat to gaming history, and that I would later become a gaming historian among other things, I would doubtless have taken more interest in them. As it was, though, they were just a couple of older guys with uncool MS-DOS computers wanting to see what an Amiga could do.

A year or two after finishing high school, I interviewed for a job at Apogee, which was by then flying high. Again, had I known what my future held I would have paid more attention to my surroundings; I retain only the vaguest impression of a chaotic but otherwise unremarkable-looking office. Scott and George were perceptive enough to realize that I would never have fit in with them, and didn’t hire me. For this I bear them no ill will whatsoever, given that their choice not to do so was the best one for all of us; I would have been miserable there. I believe that the day of that interview in 1991 or 1992 was the last time I ever saw Scott and George; Scott and my sister broke up permanently shortly thereafter if not before.

The company once known as Apogee, which is now known as 3D Realms, has released all of their old shareware games for free on their website. Daniel Berke and Matthew Engle continue to maintain their old games in updated versions that work with modern incarnations of Windows; you can download them and purchase registrations on the 11th Dimension Entertainment home page.)

Original URL: https://www.filfre.net/2020/05/the-shareware-scene-part-2-the-question-of-games/