From The CRPG Addict

|

| Crusaders of the Dark Savant is the first game for which this import process has implications beyond character attributes and equipment. |

If a developer allows meaningful choices in the game, how does he reflect the consequences of those choices in sequels? This question grows more and more pertinent as the years pass, and meaningful choices become a greater expectation among RPG players. Indeed, it is common on today’s blogs and discussion forums for players to insist that meaningful choices–affecting the direction of the plot and the ending of the game–are an essential part of a role-playing game. Such a claim ignores most of the history of RPGs, in which the only choice most players had was whether to attack with a sword or an axe, but I’m willing to allow that true role-playing choices might become an essential characteristic of a twenty-first century RPG.

The issue becomes pertinent for essentially the first time in Crusaders of the Dark Savant (1992), a sequel to a game in which the player’s choices could produce one of three different endings. This isn’t quite the first time this happened, but previous “alternate endings” were either just creative deaths (i.e., ways of not winning the game), such as the “bad” endings of Dungeon Master (1987), Ultima V (1988), Pool of Radiance (1988), or The Magic Candle (1989), or alternate paths that funneled to the same basic ending, as in the Quest for Glory series (1988-1992), Dragon Wars (1989), Sword of Aragon (1989), or Disciples of Steel (1991). Prior to Wizardry VI: Bane of the Cosmic Forge (1990), the only game I can think of that offered true alternate ways of winning the game was the roguelike Omega (1988), and it didn’t have a sequel. Slightly earlier, however, Phantasie II (1986) and III (1987) chanced some introductory dialogue depending on whether the party was created or imported, reflecting the player’s choice to have finished the previous games at all.

|

| Phantasie III his Filmon say that Nikademus would “never suspect you” if you’re a new party. If you’re imported, he tells you that he chose you because you’d already defeated his minions before. |

I haven’t played a lot of games post-1992, but my read is that alternate endings aren’t necessarily common even through the modern era. The Elder Scrolls games, excepting Daggerfall, basically just have one. The Infinity Engine games may have offered a lot of roleplaying in between the beginnings and ends, but they all ended basically the same. There are some notable exceptions–Fallout New Vegas, Fallout 4, the Mass Effect series, and the Dragon Age series all come to mind–but I’d be surprised if more than half of modern RPGs, no matter how many branches they offer along the way, end in more than once place.

On the other hand, even games that don’t offer multiple endings tend, these days, to include significant player-influenced changes in the world state between the beginning and the end. The main quest of Skyrim might end in the same place for everyone, but along the way either the Empire or the Stormcloaks won the war, the Dark Brotherhood is either destroyed or has just assassinated the Emperor, the Thieves’ Guild either revived or hiding in some sewers, the world either plunged into eternal night or not. These are not factors that will be possible to ignore in any sequel just because every player “defeated Alduin.”

So now that The Elder Scrolls VI is at least partly announced, what is Bethesda going to do? Based on previous games, there are several options:

1. Adopt one set of possibilities as canon. This option renders many players’ choices meaningless, but it’s easiest on the developers. It also tends to fit with what most players did by default anyway. So although you can end Baldur’s Gate with any of about 20 NPCs in your party, the developers figure at least 50% of us are going to have played with Imoen, Minsc, Jaheira, Khalid, and Dynaheir, and Baldur’s Gate II begins accordingly. In a less-obvious use of this option, most sequels assume that the players finished all the side quests and expansions in the course of winning the previous game, and thus have no problem introducing NPCs, enemies, and objects that some players may never have encountered (e.g., the player of Ultima VII Part Two starts with the Black Sword even if he never played the Forge of Virtue expansion to the first part). The developers basically have to choose this option if they want to include the game as part of a larger universe along with films and books.

|

| A line in Skyrim assumes the player finished the Shivering Isles expansion. |

2. Set the sequel so far away in time and space that it doesn’t matter. Based on player choices, the world state at the end of Oblivion might look quite different from one Hero of Kvatch to the next, but 200 years later, during the events of Skyrim, no one cares who was head of the Fighter’s Guild in a different province at the end of the Third Era. Similarly, Fallout IV makes no references to the choices made by the protagonist of Fallout: New Vegas because there’s no communication between Nevada and Massachusetts, and both places have their own problems.

3. Account for all the possibilities. This one is pretty rare, and insane when it happens, but it’s featured quite notably in Oblivion and Skyrim to explain the events in Daggerfall. Depending on player choices in that game–the only Elder Scrolls game so far to offer multiple endings–the giant golem Numidium is activated in support of one faction (or not) and political boundaries are reconfigured to the favor of one or more factions. To deal with all possibilities, future games feature a book called The Warp in the West that basically says at the end of Daggerfall, time “broke,” Numidium was seen at multiple places, all possibilities occurred, and a trio of gods had to intervene to untangle the mess, resulting in a stable political state among four new kingdoms.

In a less dramatic option, games after Morrowind don’t take a stand on whether the Nerevarine killed the gods of the Tribunal. They’re gone, sure, but maybe they disappeared on their own.

(As an aside, one of the things I love about the Elder Scrolls lore is how many distant past events can be interpreted as if they were the results of multiple player choices retconned into the same kind of a “warp” that the developers used to explain the end of Daggerfall. Take, for example, the many conflicting characterizations of Tiber Septim. Who was he originally? Where was he from? Was he the noble hero who united an empire or the lecherous villain who seduced Barenziah and then forced her to abort their love child? Did he become a god? What about the events at Red Mountain? Did Vivec kill Nerevar? What happened to the dwarves? The implication is that major characters of Tamriel’s past, like Tiber Septim and Vivec, were player characters whose stories could have gone multiple ways. Their games just haven’t been developed.)

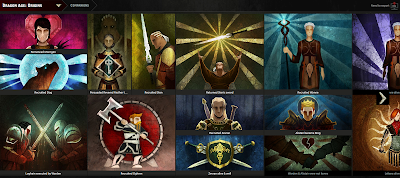

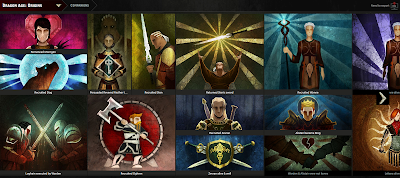

4. Dynamically adapt the plot and world state of the sequel to reflect the player’s choices. This is the rarest and most admirable option, and I can’t think of any series that does it better than Dragon Age. The games certainly have their flaws, but attention to player choice isn’t one of them. Inquisition is particularly well done. Choices both major and minor in the two previous games determined everything from the leaders of nations to the specific NPCs the player encounters, and where. (If you didn’t play the previous games, you just got defaults.) The effects on the world state, the available NPCs in the game, and the direction of the plot are significant enough that players who made different choices in Origins and Dragon Age II face very different games when they get to Inquisition. (I should also note that this dedication to adapting the world state extends to the minor expansions as well as the major titles; both Awakening and Witch Hunt for Origins start very differently depending on choices made during the main campaign.) I understand that the Mass Effect series offers the same attention to this kind of detail.

|

| The “Dragon Age Keep” web site lets you set the world state from the first two games, greatly enhancing continuity as you begin Dragon Age: Inquisition. |

While I characterize Option 4 as the most “admirable,” it’s also somewhat understandable when developers don’t take it. It greatly expands the amount of content that they have to create, much of which will never be seen by most players. It’s probably unsustainable across more than three games; certainly, it’s hard to imagine Bioware accounting for all choices in Inquisition plus the two previous games if they make a fourth one.

On the other hand, it’s horribly disappointing for the player to start a sequel and find that his choices in the previous game are ignored. Some games adopt a compromise between Option 1 and Option 4, using player choices in previous games to tweak a few variables (which might affect dialogue options) but otherwise offer the same gameplay experience. I seem to remember Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II going this route, changing a few scenes based on the result of some (clumsy) dialogue options at the beginning, but otherwise making some assumptions about how the first game progressed.

It’s easy to think of Option 4 as the most advanced option, and thus the one we expect to see later in the development of RPGs. In fact, if it was going to be commonplace, its best chance was in the 1990s, just as meaningful choices became more common, but before reacting to those choices meant significant chances to graphics and voiced dialogue. A developer can afford to be generous with simple text adaptations.

And thus we begin Crusaders of the Dark Savant with three separate sets of opening scenes, each with different text, but sharing many of the same graphics.

|

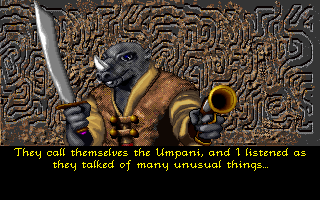

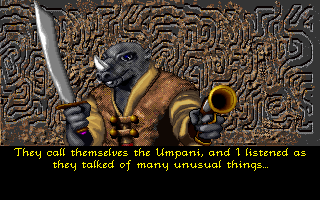

| All opening narratives show this scene, but they all use different text depending on whom the party is with. |

If the party ended Bane of the Cosmic Forge having rejected the queen, overseeing the suicide of the vampire king, and heading off into space with a friendly dragon named Bela, they soon find that Bela has made friends (over the radio) with the Umpani, a race of intelligent pachyderms. He relates the story of Guardia and the Astral Dominae and warns the party of the other factions seeking to possess it, including the Dark Savant and his T’Rang allies. They arrive at Guardia at the same time as the Dark Savant. Bela drops the party off in the forest to start looking for the Astral Dominae while he himself chases after the Dark Savant to find out what he’s up to.

|

| Bela talks about his new friends. |

If the party ended Bane by trying to take the Cosmic Forge only to be intercepted by the android Aletheides, Savant begins by having Aletheides explain that he’s been sent to retrieve the pen by the Lords of the Cosmic Circle. He relates the threat to the universe now that Guardia has been discovered, and he enlists the party to accompany him so they can find the Astral Dominae before the Dark Savant. Since he has to return to the Lords with the Forge, he drops off the party in the woods on Guardia and then takes off.

|

| Aletheides lays out his plan. |

If the party ended Forge by killing everyone and boarding Bela’s ship on their own, they’re soon swallowed up by the Dark Savant’s frigate. The Savant clearly states his intention to challenge the Lords of the Cosmic Circle and “end their stranglehold on the Destiny of the Stars.” He demands that the party assist in his search for the Astral Dominae and has them fly to Guardia on a T’Rang ship, where again they land in the woods to begin their adventure.

|

| The Dark Savant offers no chance to object. |

Finally, if the player didn’t complete Bane at all–or didn’t play it–the game assumes that they’re treasure-seekers who found the Cosmic Forge in a temple on a random world. Just as in the second option, Aletheides reaches them just before they take the pen and enlists them in his mission. As with everyone else, the party begins in the woods.

Although all parties start in a forest, they’re different forests, on different maps, and thus begin the game with quite different experiences. And because my understanding is that Savant is quite nonlinear, they probably continue with different experiences as well. What I don’t yet know is whether choices made in Bane affect anything in Savant other than the backstory and starting location. Do the various factions begin predisposed to like or dislike you? Does Bela show up again if you didn’t kill him? Those types of adaptations would be admirable, but perhaps a little too much to expect this early in the era.

I was able to download other players’ saved games to experience the different beginnings above, but in 1992, I would have been out of luck. Knowing that there were different beginnings to Savant would have made me eager to re-play Bane, independently of what I thought of its replayability as a stand-alone game, the same way that Inquisition has made me want to replay the previous games in the Dragon Age series. Thus, we see that good attention to continuity can increase the replayability of not only the current game but previous ones in the series.

Continuity of character is, of course, a separate consideration from continuity of plot. It is also far more common. We saw it as early as 1979, with the ability to move the same character among multiple Dunjonquest modules, and most classic game series–Wizardry, Ultima, Phantasie, The Bard’s Tale, the Gold Box games–have allowed you to continue the same character or party across at least one sequel. There was even a period in the mid-1980s when you could move the same characters between franchises. As a kid, this was far more important to me than it is now. Today, I find that such games either reduce imported characters to the point that they’re hardly better than new characters or they’re so overpowered that they ruin the game. A few franchises–the Gold Box and Baldur’s Gate come to mind–have done a good job achieving balance, but on the whole I like that the modern inclination is to retain the universe but start each game with a new hero.

In that spirit, for my “real” Savant party, I’ll be starting over from scratch with a new set of characters, partly because I enjoy the early levels the most, and partly because the game assumed I did that anyway (I must have screwed up something with my saved game in Bane). We’ll pick up with the adventures of the new party in New City after a detour to investigate the German Die Dunkle Dimension.

In the meantime, which continuity options do you prefer? What games best exemplify them? What other methods have you seen for reflecting player choices across the game’s universe?

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2018/08/plot-continuity-across-sequels-ft.html