From The CRPG Addict

|

| Congratulations! Here’s a near-unreadable screen! |

Ultizurk II: The Shadow Master

United States

Independently developed and published

Released in 1992 for DOS

Date Started: 26 March 2019

Date Finished: 7 April 2019

Total Hours: 16

Difficulty: Moderate (3/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

Difficulty: Moderate (3/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

Summary:

One of a long-running series of independent games, Ultizurk II borrows its basic approach and many of its plot elements from Ultima games. Although more complicated than Ultizurk I, the author was still an amateur, which comes through in under-developed character development, combat, and inventory systems. There are some decent puzzle-solving moments, but the game overall is too large and too long for its extremely basic approach to role-playing.

****

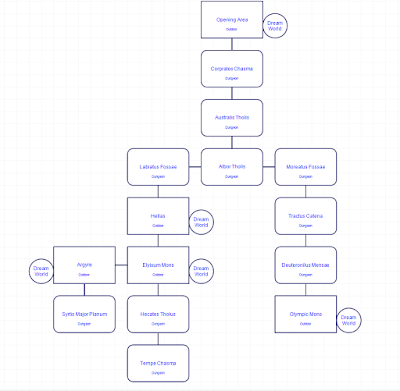

Ultizurk II ended up comprising five outdoor maps, nine dungeon maps, and 5 “dream world” maps, all 64 x 64. This is far too big for a game of such limited playability. The maps exist in a mostly linear manner, which makes it a nightmare to go back and forth among the areas as you try to solve the various puzzles. Walking through the dungeons isn’t hard, if you bring enough herbs, but it’s long, particularly with the clunky interface and the need to stop and toss sling stones at monsters every five steps. Towards the end of the game, I just couldn’t take it anymore, and I confess that I used a hex editor to figure out the character’s saved coordinates and manipulate them to get him through the dungeons faster.

|

| The order of the game’s maps. |

You’ll note that all the areas are, indeed, named after features on Mars, although sometimes misspelled or otherwise a bit mangled. I was authoritatively not on Mars for this game, however, as the residents are always referred to as “Arcturians.”

|

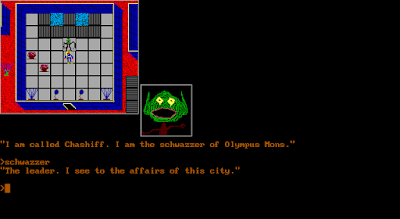

| In Arcturian, leaders are called “schwazzers.” Got it. |

All of the dungeon maps were swarming with monsters. Most of the outdoor maps were, too, but a couple were monster-free. As promised by the manual, each of the cities outside the starting area had one or two NPCs. They all responded to NAME and JOB and then suggested keywords in their responses. Sometimes, the keywords were a bit unintuitive, such as when the leader of the planet says, “I see you are trying to help us, but alas!,” and the next prompt is not HELP but ALAS. None of them had much to say in general, and the game missed on opportunity to better flesh out the game world with these dialogues. None of them had anything to say about any water crisis, and almost all of the maps had a fountain or two, suggesting no crisis at all.

The Shadow Master had laid it out last time: my goal was to collect three crystals for each city’s mind machine (five total machines), use the crystals to power the machines, enter the dream worlds, and collect an orb from each. The machines require specific crystals in a specific order; the ones a machine requires are usually found closest to that machine. What you don’t want to do is wait until you have a bunch of crystals and then try to figure out what machine uses which ones and in which order. That takes forever and there’s no way to solve it but trial and error.

|

| Slotting crystals into a dream machine. |

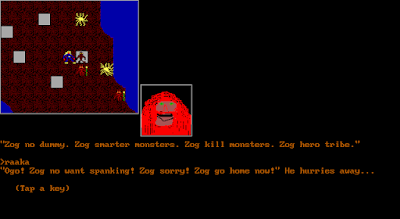

A lot of the crystals are found lying on the ground within dungeons. The three used by the machine in Olympus Mons are dug up from shrines on that map. A few other crystals require you to solve side-quests. For instance, a caveman named Oog would give me a crystal if I could find his kinsman Zog (another Ultima VI reference) and get him to return. The two cavemen were several maps away, so that was a bit of a pain. Another required me to find some blue glass, have it refined by a glass smith, then have it assembled into a gem by a gem maker.

|

| Finding Zog in a dungeon. That might be the worst NPC portrait in history. |

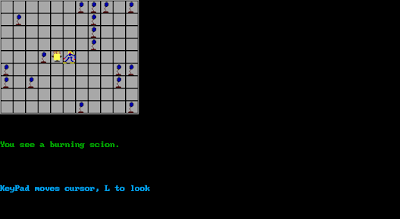

The dream worlds all had their own puzzles. Most of them were navigational, such as one that had a bunch of invisible walls and required me to find my way to a bunch of lit braziers and douse them with a bucket of water. When I was done, the bucket of water turned into an orb in my inventory, but there was no message to accompany this, so I spent an extra hour just wandering this level, wondering what I was missing.

|

| Dousing braziers on a level full of lamps and invisible walls. |

Another dream world puzzle had the player nonsensically meet Wyatt Earp, who was trying to figure out how to best apportion sacks of feed among his buffalo ranch. It was basically a magic square puzzle–the columns and rows had to add up to 10–except with repeating values for the sacks (1,1,2,3,3,4,5,5,6) and no requirement that the values add up to 10 on the diagonals. There are systems for solving magic squares with nonrepeating values, and you can even do it with algebra, but at the time I couldn’t figure out a formula that would work with this nonstandard version. Eventually, I just solved it through trial and error.

|

| Helping Wyatt Earp feed buffalo by solving a magic square puzzle does, admittedly, sound like something that would happen in one of my dreams. |

When I had all five orbs, I slogged all the way back to the starting area and placed them in their receptacles in the transportation room. Supposedly, I just had to mentally concentrate on where I wanted to go, and I’d go there. Instead, I got a message that said “Overload! Overload! Overload! Machinery too old!” and the orbs all burst into flame.

|

| Like trying to run any modern PC game on a one-year-old laptop. |

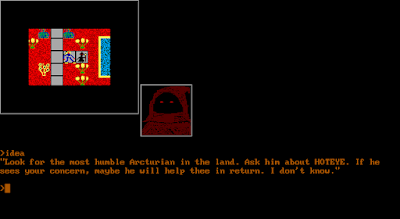

The Shadow Master had nothing to offer about this turn of events, but he did say that he’d dug up an obscure keyword (HOTEYE) that I should mention to the humblest person I had met. Well, I hadn’t met any clearly humble people, but neither had I met so many people that I couldn’t swing by all of them with message. The intended recipient turned out to be Krindell, an Arcturian in Hellas who I’d previously dismissed as a lunatic because he just went on about flowers and how they teach him of the heart.

Krindell turned out to be the leader of the planet. The HOTEYE keyword led to a discussion of “the lens,” a theoretical construct that would melt a glacier in Elysium Mons, thus “restoring the water balance.” But the lens “needs a master” and only an “enlightened one” can create it. “If you have been virtuous, then legend says that the lens will stare you in the eye.”

|

| Would it have been that hard to make a lens using actual lens-making equipment? |

There really isn’t a way in this game to demonstrate virtue, which is why it was a good thing that, following the conversation, a lens just magically appeared on the ground next to Krindell. That was a pretty lame plot development. I suspect Dr. Dungeon originally had a more lengthy side quest in mind for acquiring the lens.

I took it to Elysium Mons and placed it in an obvious square. The glacier partly melted, leaving a river flowing through it.

|

| But did it really happen, or was it just implanted? |

Walking up the river, I encountered a generator at the top. When I tried to “use,” it told me to enter the “activation sequence.” I had no notes for anything like that, so I spent some time going around asking NPCs about it. Krindell still acted as if I hadn’t already gotten the lens, and the Shadow Master was still stuck on HOTEYE. After about an hour of futile wandering, I inspected the game’s code and found that the answer was “1175.” Apparently, it’s found on one of the signs scattered throughout the game, which it turns out you have to “use” to read; “looking” at them just tells you that they’re signs.

|

| Any true sci-fi fan would have gone with 1138. |

Entering the code brought about the long endgame. First, a computer display lit up on the generator, an automated mechanism engaged, and I had to re-enter the code. “Intergalactic transmission incoming,” it then said, and the face of an alien popped up.

Greetings, Earthling. Millions of years ago, our race had already developed space travel. We grew in knowledge and stature. We became as gods. We started with virtues similar to thine own. The planet thou hast seen was an experiment in genetics–the creation of life from inanimate matter. We do this because we respect all life, from the smallest microbe to the largest whale. Our policy is not to intervene once we have created a planet and brought life forth from it. The natural way of things must be allowed its course.The planet thou hast just visited is but one among thousands like it which we developed countless eons ago. It developed along the usual evolutional pattern, but a problem arose with atmospheric pressure. Mathematical probability estimated life could only be sustained for a further maximum of four hundred years.Then YOU came. Forgive our bluntness, but we’ve never seen such a primitive being display such compassion. You saved an entire world from certain death. You persevered for months. When the teleporter failed, you turned attention away from yourself and towards the planet’s need. The galaxies themselves sing your praise!

|

| That sounds great, but how, functionally, do they do that? |

I felt that was laying it on a little thick, particularly since I didn’t bother to help the planet until it appeared that I was stuck there. Anyway, the aliens somehow transported me off-planet, and I was able to witness a little graphics show by which “the red and brown planet turned blue with water and green with grass again!”

|

| Someone recently discovered vector graphics, I see. |

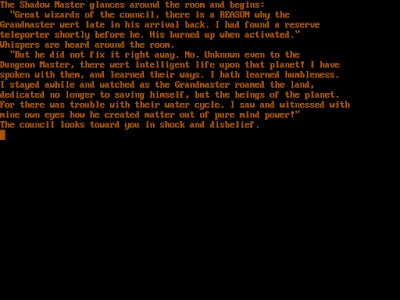

Then, somehow I was transported home to the Wizards’ Guild. The Dungeon Master began speaking and announced the end to the “contest . . . between the two top adventurers in the world,” namely the Shadow Master–that’s apparently his actual name–and me. This retcons the end of Ultizurk I a bit, where the Shadow Master kidnapped me and I didn’t voluntarily enter a contest.

The Shadow Master was named the new Guild Master given that he returned first. But the Shadow Master got up and made a speech in which he recounted my adventures, said that I had somehow “created matter out of pure mind power!,” and praised my selfless rescue of the Arcturians. At his recommendation the Council unanimously made me the Guild Master, and the Shadow Master went off to take over the Thieves’ Guild, where he “forgot all about his new-found humbleness.”

|

| The Shadow Master falls on his sword. |

This conclusion slightly undermines one of my complaints, that the game, despite its subtitle, isn’t really about the Shadow Master. But only slightly.

We’ll let it all sink in while I score the game:

- 2 points for the game world. None of it makes much sense, and it depends too heavily on recycled plot elements from the Ultima series, particularly Martian Dreams.

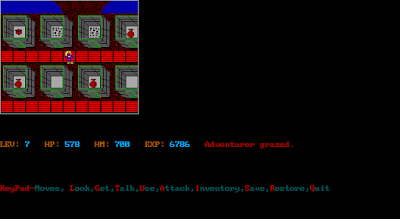

- 1 point for character creation and development. There’s no creation, and development is a matter of getting extra maximum hit points at weird intervals. I seemed to hit the level cap (Level 7) awfully early in the game.

- 3 points for NPC interaction. No game that adopts a keyword dialogue system is entirely bad, but there aren’t very many NPCs, and the interaction lacks the complexity of the Ultima titles. The bland Arcturians almost made me think fondly of the NPC in Ultizurk I who called me “granmassa” and wanted a potion of healing for her “po’ lil chile.”

|

| The Shadow Master’s characterization was, I admit, a bit unexpected. |

- 2 points for encounters and foes. It gets that for the occasionally-good puzzle. The various enemies roaming around the map are just icons with nothing of interest about them.

- 1 point for magic and combat. There’s no magic system (odd given that the character is a wizard), and the combat system consists of selecting “attack” and specifying the foe.

- 2 points for equipment. It gets both those points for the somewhat-interesting herb system. I never found any weapons other than the starting club and sling. There’s no armor or usable items. This is another area in which Ultizurk I was better.

|

| Loot areas like this one in Syrtis Major Planum don’t offer anything but sling stones and food. |

- 0 points for no economy.

- 2 points for a main quest with no choices or alternate endings.

- 2 points for graphics, sound, and interface. There are times that the graphics hold up, and some of the commands work well, but as a while the interface is clunky, the screen makes poor use of its real estate, and the sounds are harsh and offensive to the ears.

|

| Even with the inventory window up, the game wastes a lot of screen space. |

- 2 points for gameplay, mostly for a balanced level of difficulty. None of the other things that I look for–nonlinearity, replayability, and a proper length for its content–are present in the game.

That gives us a final score of 17, a bit lower than I ranked Ultizurk I. But Robert Deutsch is growing as a developer, and I find myself looking forward to Ultizurk III (1993; a two-part game) which, judging by screenshots, at least fixes the screen composition problem. We’ll also have The Great Ultizurkian Underland (1993), Wraith (1995) and Madman (1996) to enjoy. Although I’ve rated Ultizurk II a bit miserably, when you read comments by Dr. Dungeon like this one in an RPG Codex thread, you can’t help but root for the guy. If loving RPG development is wrong, he just doesn’t want to be right.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/04/ultizurk-ii-won-with-summary-and-rating.html