There are two stories to be told about games on Microsoft Windows during the operating environment’s first ten years on the market. One of them is extremely short, the other a bit longer and far more interesting. We’ll dispense with the former first.

During the first half of the aforementioned decade — the era of Windows 1 and 2 — the big game publishers, like most of their peers making other kinds of software, never looked twice at Microsoft’s GUI. Why should they? Very few people were even using the thing.

Yet even after Windows 3.0 hit the scene in 1990 and makers of other kinds of software stampeded to embrace it, game publishers continued to turn up their noses. The Windows API made life easier in countless ways for makers of word processors, spreadsheets, and databases, allowing them to craft attractive applications with a uniform look and feel. But it certainly hadn’t been designed with games in mind; they were so far down on Microsoft’s list of priorities as to be nonexistent. Games were in fact the one kind of software in which uniformity wasn’t a positive thing; gamers craved diverse experiences. As a programmer, you couldn’t even force a Windows game to go full-screen. Instead you were stuck all the time inside the borders of the window in which it ran; this, needless to say, didn’t do much for immersion. It was true that Windows’s library for programming graphics, known as the Graphics Device Interface, or GDI, liberated programmers from the tyranny of the hardware — from needing to program separate modules to interact properly with every video standard in the notoriously diverse MS-DOS ecosystem. Unfortunately, though, GDI was slow; it was fine for business graphics, but unusable for most of the popular game genres.

For all these reasons, game developers, alone among makers of software, stuck obstinately with MS-DOS throughout the early 1990s, even as everything else in mainstream computing went all Windows, all the time. It wouldn’t be until after the first decade of Windows was over that game developers would finally embrace it, helped along both by a carrot (Microsoft was finally beginning to pay serious attention to their needs) and a stick (the ever-expanding diversity of hardware on the market was making the MS-DOS bare-metal approach to programming untenable).

End of story number one.

The second, more interesting story about games on Windows deals with different kinds of games from the ones the traditional game publishers were flogging to the demographic who were happy to self-identify as gamers. The people who came to play these different kinds of games couldn’t imagine describing themselves in those terms — and, indeed, would likely have been somewhat insulted if you had suggested it to them. Yet they too would soon be putting in millions upon millions of hours every year playing games, albeit more often in antiseptic adult offices than in odoriferous teenage bedrooms. Whatever; the fact was, they were still playing games. In fact, they were playing games enough to make Windows, that alleged game-unfriendly operating environment, quite probably the most successful gaming platform of the early 1990s in terms of sheer number of person-hours spent playing. And all the while the “hardcore” gamers barely even noticed this most profound democratization of computer gaming that the world had yet seen.

Microsoft Windows, like its inspiration the Apple Macintosh, used what’s known as a skeuomorphic interface — an interface built out of analogues to real-world objects, such as paper documents, a desktop, and a trashcan — to present a friendlier face of computing to people who may have been uncomfortable with the blinking command prompt of yore. It thus comes as little surprise that most of the early Windows games were skeuomorphic as well, being computerized versions of non-threateningly old-fashioned card and board games. In this, they were something of a throwback to the earliest days of personal computing in general, when hobbyists passed around BASIC versions of these same hoary classics, whose simple designs constituted some of the only ones that could be made to fit into the minuscule memories of the first microcomputers. With Windows, it seemed, the old had become new again, as computer gaming started over to try to capture a whole new demographic.

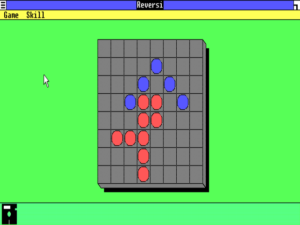

The very first game ever programmed to run in Windows is appropriately prototypical. When Tandy Trower took over the fractious and directionless Windows project at Microsoft in January of 1985, he found that a handful of applets that weren’t, strictly speaking, a part of the operating environment itself had already been completed. These included a calculator, a rudimentary text editor, and a computerized version of a board game called Reversi.

Reversi is an abstract game for two players that looks a bit like checkers and plays like a faster-paced, simplified version of the Japanese classic Go. Its origins are somewhat murky, but it was first popularized as a commercial product in late Victorian England. In 1971, an enterprising Japanese businessman made a couple of minor changes to the rules of this game that had long been considered in the public domain, patented the result, and started selling it as Othello. Under this name, it enjoys modest worldwide popularity to this day. Under both of its names, it also became an early favorite on personal computers, where its simple rules and relatively constrained possibility space lent themselves well to the limitations of programming in BASIC on a 16 K computer; Byte magazine, the bible of early microcomputer hackers, published a type-in Othello as early as its October 1977 issue.

A member of the Windows team named Chris Peters had decided to write a new version of the game under its original (and non-trademarked) name of Reversi in 1984, largely as one of several experiments — proofs of concept, if you will — into Windows application programming. Tandy Trower then pushed to get some of his team’s experimental applets, among them Reversi, included with the first release of Windows in November of 1985:

When the Macintosh was announced, I noted that Apple bundled a small set of applications, which included a small word processor called MacWrite and a drawing application called MacPaint. In addition, Lotus and Borland had recently released DOS products called Metro and SideKick that consisted of a small suite of character-based applications that could be popped up with a keyboard combination while running other applications. Those packages included a simple text editor, a calculator, a calendar, and a business-card-like database. So I went to [Bill] Gates and [Steve] Ballmer with the recommendation that we bundle a similar set of applets with Windows, which would include refining the ones already in development, as well as a few more to match functions comparable to these other products.

Interestingly, MacOS did not include any games among its suite of applets, apart from a minimalist sliding-number puzzle that filled all of 600 bytes. Apple, whose Apple II was found in more schools and homes than businesses and who were therefore viewed with contempt by much of the conservative corporate computing establishment, ran scared from any association of their latest machine with games. But Microsoft, on whose operating system MS-DOS much of corporate America ran, must have felt they could get away with a little more frivolity.

Still, Windows Reversi didn’t ultimately have much impact on much of anyone. Reversi in general was a game more suited to the hacker mindset than the general public, lacking the immediate appeal of a more universally known design, while the execution of this particular version of Reversi was competent but no more. And then, of course, very few people bought Windows 1 in the first place.

For a long time thereafter, Microsoft gave little thought to making more games for Windows. Reversi stuck around unchanged in the only somewhat more successful Windows 2, and was earmarked to remain in Windows 3.0 as well. Beyond that, Microsoft had no major plans for Windows gaming. And then, in one of the stranger episodes in the whole history of gaming, they were handed the piece of software destined to become almost certainly the most popular computer game of all time, reckoned in terms of person-hours played: Windows Solitaire.

The idea of a single-player card game, perfect for passing the time on long coach or railway journeys, had first spread across Europe and then the world during the nineteenth century. The game of Solitaire — or Patience, as it is still more commonly known in Britain — is really a collection of many different games that all utilize a single deck of everyday playing cards. The overarching name is, however, often used interchangeably with the variant known as Klondike, by far the most popular form of Solitaire.

Klondike Solitaire, like the many other variants, has many qualities that make it attractive for computer adaptation on a platform that gives limited scope for programmer ambition. Depending on how one chooses to define such things, a “game” of Solitaire is arguably more of a puzzle than an actual game, and that’s a good thing in this context: the fact that this is a truly single-player endeavor means that the programmer doesn’t have to worry about artificial intelligence at all. In addition, the rules are simple, and playing cards are fairly trivial to represent using even the most primitive computer graphics. Unsurprisingly, then, Solitaire was another favorite among the earliest microcomputer game developers.

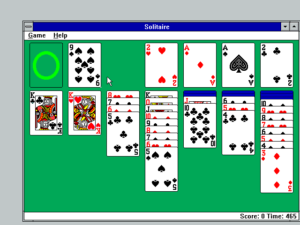

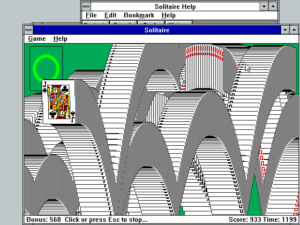

It was for all the same reasons that a university student named Wes Cherry, who worked at Microsoft as an intern during the summer of 1988, decided to make a version of Klondike Solitaire for Windows that was similar to one he had spent a lot of time playing on the Macintosh. (Yes, even when it came to the games written by Microsoft’s interns, Windows could never seem to escape the shadow of the Macintosh.) There was, according to Cherry himself, “nothing great” about the code of the game he wrote; it was no better nor worse than a thousand other computerized Solitaire games. After all, how much could you really do with Solitaire one way or the other? It either worked or it didn’t. Thankfully, Cherry’s did, and even came complete with a selection of cute little card backs, drawn by his girlfriend Leslie Kooy. Asked what was the hardest aspect of writing the game, he points today to the soon-to-be-iconic cascade of cards that accompanied victory: “I went through all kinds of hoops to get that final cascade as fast as possible.” (Here we have a fine example of why most game programmers held Windows in such contempt…) At the end of his summer internship, he put his Solitaire on a server full of games and other little experiments that Microsoft’s programmers had created while learning how Windows worked, and went back to university.

Months later, some unknown manager at Microsoft sifted through the same server and discovered Cherry’s Solitaire. It seems that Microsoft had belatedly started looking for a new game — something more interesting than Reversi — to include with the upcoming Windows 3.0, which they intended to pitch as hard to consumers as businesspeople. They now decided that Solitaire ought to be that game. So, they put it through a testing process, getting Cherry to fix the bugs they found from his dorm room in return for a new computer. Meanwhile Susan Kare, the famed designer of MacOS’s look who was now working for Microsoft, gave Leslie Kooy’s cards a bit more polishing.

And so, when Windows 3.0 shipped in May of 1990, Solitaire was included. According to Microsoft, its purpose was to teach people how to use a GUI in a fun way, but that explanation was always something of a red herring. The fact was that computing was changing, machines were entering homes in big numbers once again, and giving people a fun game to play as part of an otherwise serious operating environment was no longer anathema. Certainly huge numbers of people would find Solitaire more than compelling enough as an end unto itself.

The ubiquity that Windows Solitaire went on to achieve — and still maintains to a large extent to this day1 — is as difficult to overstate as it is to quantify. Microsoft themselves soon announced it to be the “most used” Windows application of all, easily besting heavyweight businesslike contenders like Word, Excel, Lotus 1-2-3, and WordPerfect. The game became a staple of office life all over the world, to be hauled out during coffee breaks and down times, to be kept always lurking minimized in the background, much to the chagrin of officious middle managers. By 1994, a Washington Post article would ask, only half facetiously, if Windows Solitaire was sowing the seeds of “the collapse of American capitalism.”

“Yup, sure,” says Frank Burns, a principal in the region’s largest computer bulletin board, the MetaNet. “You used to see offices laid out with the back of the video monitor toward the wall. Now it’s the other way around, so the boss can’t see you playing Solitaire.”

“It’s swallowed entire companies,” says Dennis J. “Gomer” Pyles, president of Able Bodied Computers in The Plains, Virginia. “The water-treatment plant in Warrenton, I installed [Windows on] their systems, and the next time I saw the client, the first thing he said to me was, ‘I’ve got 2000 points in Solitaire.’”

Airplanes full of businessmen resemble not board meetings but video arcades. Large gray men in large gray suits — lugging laptops loaded with spreadsheets — are consumed by beating their Solitaire scores, flight attendants observe.

Some companies, such as Boeing, routinely remove Solitaire from the Windows package when it arrives, or, in some cases, demand that Microsoft not even ship the product with the game inside. Even PC Magazine banned game-playing during office hours. “Our editor wanted to lessen the dormitory feel of our offices. Advertisers would come in and the entire research department was playing Solitaire. It didn’t leave the best impression,” reported Tin Albano, a staff editor.

Such articles have continued to crop up from time to time in the business pages ever since — as, for instance, the time in 2006 when New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg summarily terminated an employee for playing Solitaire on the job, creating a wave of press coverage both positive and negative. But the crackdowns have always been to no avail; it’s as hard to imagine the modern office without Microsoft Solitaire as it is to imagine it without Microsoft Office.

Which isn’t to say that the Solitaire phenomenon is limited to office life. My retired in-laws, who have quite possibly never played another computer game in either of their lives, both devote hours every week to Solitaire in their living room. A Finnish study from 2007 found it to be the favorite game of 36 percent of women and 13 percent of men; no other game came close to those numbers. Even more so than Tetris, that other great proto-casual game of the early 1990s, Solitaire is, to certain types of personality at any rate, endlessly appealing. Why should that be?

To begin to answer that question, we might turn to the game’s pre-digital past. Lady Cadogan’s Illustrated Games of Patience, a compendium of many Solitaire variants, was first published in 1876. Its introduction is fascinating, presaging much of the modern discussion about Microsoft Solitaire and casual gaming in general.

In days gone by, before the world lived at the railway speed as it is doing now, the game of Patience was looked upon with somewhat contemptuous toleration, as a harmless but dull amusement for idle ladies, and was ironically described as “a roundabout method of sorting the cards”; but it has gradually won for itself a higher place. For now, when the work, and still more the worries, of life have so enormously increased and multiplied, the value of a pursuit interesting enough to absorb the attention without unduly exciting the brain, and so giving the mind a rest, as it were, a breathing space wherein to recruit its faculties, is becoming more and more recognised and appreciated.

In addition to illustrating how concerns about the pace of contemporary life and nostalgia for the good old days are an eternal part of the human psyche, this passage points to the heart of Solitaire’s appeal, whether played with real cards or on a computer: the way that it can “absorb the attention without unduly exciting the brain.” It’s the perfect game to play when killing time at the end of the workday, as a palate cleanser between one task and another, or, as in the case of my in-laws, as a semi-active accompaniment to the idle practice of watching the boob tube.

Yet Solitaire isn’t a strictly rote pursuit even for those with hundreds of hours of experience playing it; if it was, it would have far less appeal. Indeed, it isn’t even particularly fair. About 20 percent of shuffles will result in a game that isn’t winnable at all, and Wes Cherry’s original computer implementation at least does nothing to protect you from this harsh mathematical reality. Still, when you get stuck there’s always that “Deal” menu option waiting for you up there in the corner, a tempting chance to reshuffle the cards and try your hand at a new combination. So, while Solitaire is the very definition of a low-engagement game, it’s also a game that has no natural end point; somehow the “Deal” option looks equally tempting whether you’ve just won or just lost. After being sucked in by its comfortable similarity to an analog game of cards almost everyone of a certain age has played, people can and do proceed to keep playing it for a lifetime.

As in the case of Tetris, there’s room to debate whether spending so many hours upon such a repetitive activity as playing Solitaire is psychologically healthy. For my own part, I avoid it and similar “time waster” games as just that — a waste of time that doesn’t leave me feeling good about myself afterward. By way of another perspective, though, there is this touching comment that was once left by a Reddit user to Wes Cherry himself:

I just want to tell you that this is the only game I play. I have autism and don’t game due to not being able to cope with the sensory processing – but Solitaire is “my” game.

I have a window of it open all day, every day and the repetitive clicking is really soothing. It helps me calm down and mentally function like a regular person. It makes a huge difference in my quality of life. I’m so glad it exists. Never thought there would be anyone I could thank for this, but maybe I can thank you. *random Internet stranger hugs*

Cherry wrote Solitaire in Microsoft’s offices on company time, and thus it was always destined to be their intellectual property. He was never paid anything at all, beyond a free computer, for creating the most popular computer game in history. He says he’s fine with this. He’s long since left the computer industry, and now owns and operates a cider distillery on Vashon Island in Puget Sound.

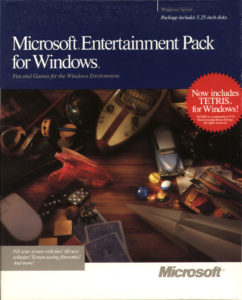

The popularity of Solitaire convinced Microsoft, if they needed convincing, that simple games like this had a place — potentially a profitable place — in Windows. Between 1990 and 1992, they released four “Microsoft Entertainment Packs,” each of which contained seven little games of varying degrees of inspiration, largely cobbled together from more of the projects coded by their programmers in their spare time. These games were the polar opposite of the ones being sold by traditional game publishers, which were growing ever more ambitious, with increasingly elaborate storylines and increasing use of video and sound recorded from the real world. The games from Microsoft were instead cast in the mold of Cherry’s Solitaire: simple games that placed few demands on either their players or the everyday office computers Microsoft envisioned running them, as indicated by the blurbs on the boxes: “No more boring coffee breaks!”; “You’ll never get out of the office!” Bruce Ryan, the manager placed in charge of the Entertainment Packs, later summarized the target demographic as “loosely supervised businesspeople.”

The centerpiece of the first Entertainment Pack was a passable version of Tetris, created under license from Spectrum Holobyte, who owned the computer rights to the game. Wes Cherry, still working out of his dorm room, provided a clone of another older puzzle game called Pipe Dream to be the second Entertainment Pack’s standard bearer; he was even compensated this time, at least modestly. As these examples illustrate, the Entertainment Packs weren’t conceptually ambitious in the least, being largely content to provide workmanlike copies of established designs from both the analog and digital realms. Among the other games included were Solitaire variants other than Klondike, a clone of the Activision tile-matching hit Shanghai, a 3D Tic-tac-toe game, a golf game (for the ultimate clichéd business-executive experience), and even a version of John Horton Conway’s venerable study of cellular life cycles, better known as the game of Life. (One does have to wonder what bored office workers made of that).

Established journals of record like Computer Gaming World barely noticed the Entertainment Packs, but they sold more than half a million copies in two years, equaling or besting the numbers of the biggest hardcore hits of the era, such as the Wing Commander series. Yet even that impressive number rather understates the popularity of Microsoft’s time wasters. Given that they had no copy protection, and given that they would run on any computer capable of running Windows, the Entertainment Packs were by all reports pirated at a mind-boggling rate, passed around offices like cakes baked for the Christmas potluck.

For all their success, though, nothing on any of the Entertainment Packs came close to rivaling Wes Cherry’s original Solitaire game in terms of sheer number of person-hours played. The key factor here was that the Entertainment Packs were add-on products; getting access to these games required motivation and effort from the would-be player, along with — at least in the case of the stereotypical coffee-break player from Microsoft’s own promotional literature — an office environment easygoing enough that one could carry in software and install it on one’s work computer. Solitaire, on the other hand, came already included with every fresh Windows installation, so long as an office’s system administrators weren’t savvy and heartless enough to seek it out and delete it. The archetypal low-effort game, its popularity was enabled by the fact that it also took no effort whatsoever to gain access to it. You just sort of stumbled over it while trying to figure out this new Windows thing that the office geek had just installed on your faithful old computer, or when you saw your neighbor in the next cubicle playing and asked what the heck she was doing. Five minutes later, it had its hooks in you.

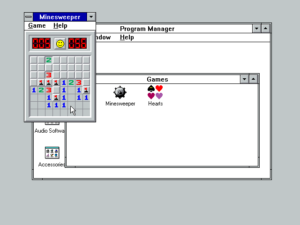

It was therefore significant when Microsoft added a new game — or rather an old one — to 1992’s Windows 3.1. Minesweeper had actually debuted as part of the first Entertainment Pack, where it had become a favorite of quite a number of players. Among them was none other than Bill Gates himself, who became so addicted that he finally deleted the game from his computer — only to start getting his fix on his colleagues’ machines. (This creates all sorts of interesting fuel for the imagination. How do you handle it when your boss, who also happens to be the richest man in the world, is hogging your computer to play Minesweeper?) Perhaps due to the CEO’s patronage, Minesweeper became part of Windows’s standard equipment in 1992, replacing the unloved Reversi.

Unlike Solitaire and most of the Entertainment Pack games, Minesweeper was an original design, written by staff programmers Robert Donner and Curt Johnson in their spare time. That said, it does owe something to the old board game Battleship, to very early computer games like Hunt the Wumpus, and in particular to a 1985 computer game called Relentless Logic. You click on squares in a grid to uncover their contents, which can be one of three things: nothing at all, indicating that neither this square nor any of its adjacent squares contain mines; a number, indicating that this square is clear but said number of its adjacent squares do contain mines; or — unlucky you! — an actual mine, which kills you, ending the game. Like Solitaire, Minesweeper straddles the line — if such a line exists — between game and puzzle, and it isn’t a terribly fair take on either: while the program does protect you to the extent that the first square you click will never contain a mine, it’s possible to get into a situation through no fault of your own where you can do nothing but play the odds on your next click. But, unlike Solitaire, Minesweeper does have more of the trappings of a conventional videogame, including a timer which encourages you to play quickly to achieve the maximum score.

Doubtless because of those more overt videogame trappings, Minesweeper never became quite the office fixture that Solitaire did. Those who did get sucked in by it, however, found it even more addictive, perhaps not least because it does demand a somewhat higher level of engagement. It too became an iconic part of life with Microsoft Windows, and must rank high on any list of most-played computer games of all time, if the data only existed to compile such a thing. After all, it did enjoy one major advantage over even Solitaire for office workers with uptight bosses: it ran in a much smaller window, and thus stood out far less on a crowded screen when peering eyes glanced into one’s cubicle.

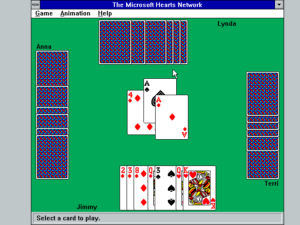

Microsoft included a third game with Windows for Workgroups 3.1, a variant intended for a networked office environment. True to that theme, Hearts was a version of the evergreen card game which could be played against computer opponents, but which was most entertaining when played together by up to four real people, all on separate computers. Its popularity was somewhat limited by the fact that it came only with Windows for Workgroups, but, again, that adjective is relative. By any normal computer-gaming standard, Hearts was hugely popular indeed for quite some years, serving for many people as their introduction to the very concept of online gaming — a concept destined to remake much of the landscape of computer gaming in general in years to come. Certainly I can remember many a spirited Hearts tournament at my workplaces during the 1990s. The human, competitive element always made Hearts far more appealing to me than the other games I’ve discussed in this article.

But whatever your favorite happened to be, the games of Windows became a vital part of a process I’ve been documenting in fits and starts over the last year or two of writing this history: an expansion of the demographics that were playing games, accomplished not by making parents and office workers suddenly fall in love with the massive, time-consuming science-fiction or fantasy epics upon which most of the traditional computer-game industry remained fixated, but rather by meeting them where they lived. Instead of five-course meals, Microsoft provided ludic snacks suited to busy lives and limited attention spans. None of the games I’ve written about here are examples of genius game design in the abstract; their genius, to whatever extent it exists, is confined to worming their way into the psyche in a way that can turn them into compulsions. Yet, simply by being a part of the software that just about everybody, with the exception of a few Macintosh stalwarts, had on their computers in the 1990s, they got hundreds of millions of people playing computer games for the first time. The mainstream Ludic Revolution, encompassing the gamification of major swaths of daily life, began in earnest on Microsoft Windows.

(Sources: the book A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players by Jesper Juul; Byte of October 1977; Computer Gaming World of September 1992; Washington Post of March 9 1994; New York Times of February 10 2006; online articles at Technologizer, The Verge, B3TA, Reddit, Game Set Watch, Tech Radar, Business Insider, and Danny Glasser’s personal blog.)

Original URL: https://www.filfre.net/2018/08/the-games-of-windows/