There are many versions of Rogue floating about. The original was published in 1980; the one I ended up playing was a 1985 DOS-based re-release (I’m playing in order of original release, not in order of the particular edition I find). The instruction manual sets up the story: you are a rogue, plunging in to the Dungeon of Doom to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor, stolen in some distant times past from surface folk by the Dungeon Lord. I admit to a certain weakness for little stories like this at the beginning of instruction manuals. Always, in the beginning days of CRPGs, the written story in the manual promised drama, variety, and actual role-playing that the gameplay didn’t really deliver.

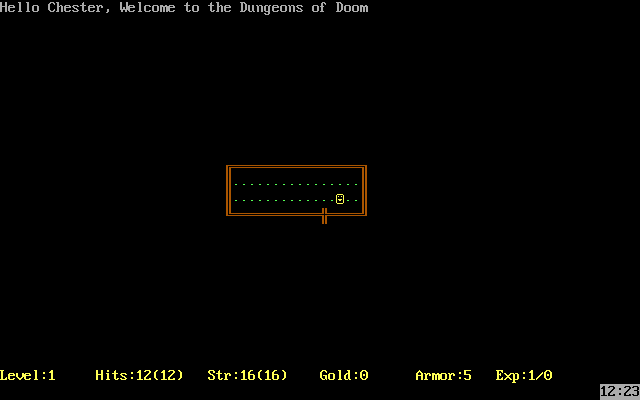

There is no character creation per se. You give your rogue a name, and you find yourself in a randomly-generated Level 1 of the Dungeon of Doom, with the same statistics and equipment every time.

|

| Entering the appropriately-named Dungeons of Doom. |

The game has a top-down perspective. Your character is represented by a little smiley face, treasures and items by various characters, and monsters by capital letters corresponding to their names–“V” for vampire, “H” for hobgoblin, and so on. There are some weird ones: what are (K)estrels and (E)mus doing in a dungeon, and why are they attacking me? There are also a few found, as far as I can tell, only in Rogue, like (A)quators (those armor-destroying sons of bitches) and (U)r-viles.

You interact with the world through simple keyboard commands: “t” to throw a weapon, “w” to wield a weapon, but “W” to wear armor, and so on. The goal is to navigate your way around, finding treasure (and especially food) until you find the stairs to the next level of the dungeon. As you descend, the monsters get progressively harder–while, oddly, the treasures don’t seem to get much better; you can just as easily find a suit of plate mail on Level 1 as you can on Level 25. (This, incidentally, turns out to be the only real way to win the game.)

The simplicity of the commands and the turn-based nature of Rogue is what I think make it so addictive. It’s a game that you can easily play for 10 or 15 minutes at a time while waiting for some code to compile or someone to show up for a meeting. There’s even a “supervisor” key that changes the screen to what looks like a DOS prompt (although having a DOS window open at all would be suspicious now days!). The game isn’t even designed as if you’re expected to win. Instead, the purpose seems to be to get the highest score possible when you either win or die. The game records your score (defined by your level and gold pieces) every time you sleep the Big Sleep. One can easily envision a time when there were thousands of Rogue players each boasting their new high score.

I wanted to win, though, and so every time I bit the dust, I howled my frustration to the walls of my study and started over again at Level 1. I lost track of how many characters–many of them maddeningly close to the Amulet of Yendor–died on me, but it must have been 50 at least.

Gold, which in early games I was delighted to see accumulating so quickly, has no value except for points. Well in to my first week of Rogue, I kept thinking I’d find a merchant somewhere who would sell me better equipment or identify my items. No such luck. What you find is dependent upon what the map randomly generates. Sometimes you might find a two-handed sword +1 on the first level; other times, you’ll find three poison potions and a cursed dagger.

|

| Our hero takes a chance on an unidentified wand and ends up polymorphing a bat into one of the most difficult monsters in the game. Time to try again… |

The luck of the draw turned out to be my salvation. On my umpteenth try, my character found both a ring and an ID scroll on Level 1. The ring turned out to be a Ring of Slow Digestion, which greatly decreased the need for constant food. With this need out of the way, I could linger on levels, slay more easy monsters, and increase my level (and hit points) faster. I could also afford to take the time to search for traps and secret doors where before my life had been a constant race to find the next bit of food. I was also extremely lucky on the next few levels finding Potions of Gain Strength, Scrolls of Increase Armor, and Scrolls of Increase Weapon which significantly boosted my stats. I learned to take off my armor at the first sight of an aquator, lest it destroy it, and I learned to throw anything I had (the game lets you throw swords and maces along with arrows and daggers) at rattlesnakes before they could bite me. But the Ring of Slow Digestion was the real winner: if I knew four months ago what I knew now, I would keep replaying Level 1 until I found one.

Once I found the Amulet of Yendor (on level 29), the game was embarrassingly easy. Once you find the amulet, you have to head back up the stairs on each level to get back to Level 1. Instead of exploring levels, you can just head up the moment you find the nearest stairs (and I had saved several Scrolls of Mapping just for that purpose). I figured the monsters would continue to be difficult all the way to the exit. But they actually decrease in difficulty as you ascend. In short order, I was in the teens and there was no real threat to me. By the time I actually got to Level 1 and there was only a snake standing between the exit and my 16th-level rogue with +4 plate mail and a +5 two-handed sword, I actually felt sorry for the poor bastard.

|

| Never stand between a rogue with the Amulet of Yendor and the exit |

The end game, I must admit, was a bit disappointing after four months of play. Would some kind of CGI cut-scene voiced by Ian McKellen have been so hard?

|

| Insult to injury: my rogue is admitted to the fighter’s guild |

The good news: I’ve been exposed to a whole new type of CRPG. And no Bioware or SSI game–not even the dreadful Pool of Radiance: Ruins of Myth Drannor will ever seem long or repetitive again. On now to the Temple of Apshai Trilogy.

****

Posts on Rogue: One | Two

Further reading: My experience with roguelikes grows with postings on Moria, Omega, early NetHack, and NetHack 3.0.