From The Adventure Gamer

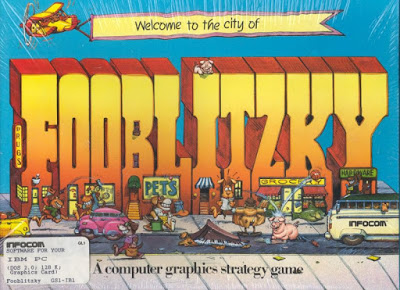

When it came to text adventures, Infocom appeared to have the golden touch. And yet, there were dark clouds looming if you knew where to look. The earliest “Zork” games still sold like hotcakes, regularly appearing on top sales charts, while newer releases packed a punch but faded just as quickly. From the beginning, the executives at Infocom wanted to diversify in order to have a robust business, one responsive to changing industry trends. Fads come and go, but Infocom was to be a company for the long term. That diversification reached a fever pitch in 1985 as the company failed to launch a new business products division. We already looked at the catastrophe that was Cornerstone. Less well-known is Infocom’s initial foray into graphical non-adventure games. That experiment also led only to a single launch, the computer board game Fooblitzky by Mike Berlyn, Brian Cody, and others.

We cannot cover Fooblitzky in the usual way. Instead, we have been inspired by Infocom’s sense of experimentation by launching an experiment of our own. Instead of my playing the game by myself, I was joined by three of our collaborators: TBD, Reiko, and Voltgloss. Even better, we recorded the game as a video which you can watch below. Considering our wide-ranging timezones, this is likely the first ever game of Fooblitzky played around the world. I’ve also embraced the spirit of experimentation by recording and editing (and then paying someone to edit better…) a video introduction to the game. It’s the first time we’ve done anything like this; please let us know in the comments below whether you want to see more such experiments in the future. Let’s have some fun with this!

|

| The introduction screen is very cute and very animated |

Our story begins in 1983. Mike Berlyn, fresh off of releasing Infidel, sought approval to launch a new skunkworks team in the company. This team would seek to do with graphical games the same thing that Infocom has already done with text adventures: make them platform agnostic. One of the key competitive advantages that made Infocom successful was that all of their games were coded for an early virtual machine. This meant that the “Imps” would compose the game in the internal language while separate platform-specific teams would write the interpreters for each machine of the era: Apple II, Commodore 64, Atari, PC, and many others. This ensured that Infocom could reach even smaller markets quickly and inexpensively. New games could also be released on every platform just about as once, subject to the needs of the marketing and distribution teams. It was “write once, run anywhere” a few decades early.

Berlyn sought to bring this flexibility to graphical games, but this was a huge challenge. While text modes of the era had differences, especially details like the number of columns on the screen (generally 40 or 80) and non-alphabetic glyphs, graphics systems had much more complexity. This included multiple resolutions, color pallets, and specialized restrictions, all of which made it challenging to work with in a cross-platform way. The Commodore 64, for example, had an excellent built-in sprite system, while the Apple II platforms had mixed text and graphics modes. The added indirection also made programs considerably slower. While you might not notice if a text adventure is “slow”, you would on a game that required timing or reflexes. In most respects, this was a brilliant idea but implemented too early. Aspects of this approach would be adopted by Sierra and other game designers in the future, but more importantly it underlies the whole “video driver” system that we take for granted since the launch of Windows. By the launch of Fooblitzky, Berlyn’s team could run their games on PC, Apple II, and Atari systems.

|

| Fooblitzky for Atari |

|

| Fooblitzky for Apple II (Image from MobyGames; I haven’t been able to get a copy to run.) |

I called Fooblitzky a computer board game, but Infocom marketing called it a “computer graphics strategy game”. Whatever it is, it is a bit of an odd duck. While Berlyn was working on the interpreter on one hand, he was assembling a team to design the game and– for the first time for Infocom– draw and animate its graphics. His team consisted of Brian Cody, a graphics designer who also contributed much of the game’s whimsical style; Paula Maxwell, an animator originally from California; and Poh Lim, a programmer. Marc Blank, co-designer of the Zork games and one of the company’s founders, also contributed his ideas to the mix.

|

| Even today, Mr. Cody’s work often displays a sense of whimsy. You can buy this and other prints at his web site. |

While on one hand the idea to do a board game may seem out of left field, it actually suited Mike Berlyn quite well. The graphical interface he was designing couldn’t support a high-performance game, so he needed something that had natural pauses like a text adventure. A strategy game was a great choice. Less remembered (and I thank Jimmy Maher for reminding me of this) is that Berlyn’s Suspended featured many aspects of a “board game” itself. While it was single player, it came with a map and game tokens to help you keep track of the location of the sensory robots. It also had some tunable parameters to make the game easier or more difficult, something that made it more of a strategy game in parts rather than an adventure. Finally, the pre-Infocom draft of that game featured graphics! When you would “look” at the rooms using Iris, the visual robot, his initial design had you switch into a graphics mode to “see” a picture of the location. Ultimately, this was dropped well before release, but his inability to support that kind of graphical experimentation may have encouraged him to solve this problem for future games.

|

| The original “game board” from Suspended |

Fooblitzky’s development continued in the background at Infocom, but the game clearly was not a good fit for the company. (Whether it was a better or worse fit than Cornerstone is best left as an exercise for the reader.) The marketing team didn’t know what to do with it. The game had cost a significant amount of time and treasure to create. Should they abandon it? In the end, they released it with a whisper. Its launch event was limited to an announcement in New Zork Times fan newsletter for Summer 1985, plus an order form:

Fooblitzky is so different and innovative that Infocom’s marketing department hit upon a different and innovative marketing approach. Because you’re a special customer of Infocom’s, because you read The New Zork Times, you can buy Fooblitzky before anyone else!

This “different and innovative” approach essentially allowed the company to push the game out the door without having to spend more than a pittance marketing it. Perhaps making it a “mail-order exclusive” for six months would encourage people to buy it for the rarity factor, but it is easy to imagine a failing game quietly dropped after six months instead. It’s not like anyone outside the fan community was even aware of it! This somewhat standoffish relationship with Marketing was even jokingly referred to in the next issue of the Times. That issue describes an informal Fooblitzky tournament around the Infocom office, but Marketing refused to participate. It’s representative, Suzan Sobel, was quoted as saying that she “would rather give birth” than play Fooblitzky. A joke? Absolutely. But I would not be surprised if that joke didn’t hide more than a shred of very real frustration in the way the game was being treated within the organization.

|

| Despite my best efforts, I have been unable to locate an original order form. |

Ultimately, Fooblitzky would be the end of the line for the Graphics Team at Infocom, although the company would embrace pixel-based art again during the Activision era. Mike Berlyn left Infocom around this time although this was far from his last game. Some sources cite his reason for leaving as a desire to work once again with his wife, Muffy Berlyn, who had been his co-designer on his pre-Infocom games and whom he would resume collaborations with after leaving. We covered his next game, Tass Times in Tonetown, way back as Game #8! That game was developed by Mr. Berlyn’s new company and distributed by Activision, potentially using contacts that he cultivated while working at Infocom through the acquisition. This may be a game that we want to revisit now that we have a much better grasp of the history of this era. Surprisingly, we will see Berlyn again in our Zork marathon when we play 1997’s Zork: The Undiscovered Underground, a text adventure tie-in to Zork Grand Inquisitor. As for the rest of the team, Brian Cody was let go from Infocom well before the game even launched. I do not know the fates of his teammates, although none of them worked on any future games that I am aware of.

Not surprising given the strange product launch, Fooblizky was not a commercial success. Leaked sales records suggest that they sold only 500 copies by mail order. In total for the entire life of the product, they sold fewer than 8,000 copies. While there is some doubt to these numbers, Fooblitzky was the least successful of the pre-Activision titles although it may have sold better than some of the later works such as the Zork Quest series.

Rules of Fooblitzky

This game’s rules aren’t impossibly complex, but they are deep enough that Infocom included a “quick start” guide alongside the main manual. For my part, I’m not sure that I “got” all of the facets of the game prior to sitting down and playing it. Let me try and sum it up.

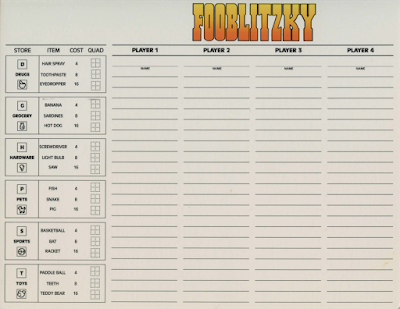

The goal of the game is to locate and purchase a set of four mystery items then bring them back to a centralized checkpoint. These items were selected by the players (or the computer, if you have fewer than four players) and so you always know your own secret-selected item. If you deduce the three others and take all four to the checkpoint, you win! Otherwise, you will be told how many of the objects you got correct and have to come back with a new set. What makes the game even deeper is that not only are you told how many items are right or wrong, but all of your fellow players are as well. In fact, nearly all of the information in the game is shared with everyone and a successful player will look at what items his friends are buying and selling to try to make decisions about what the key items may be. To help with this, the game comes with whiteboard tiles and markers to simplify and structure your deductions.

|

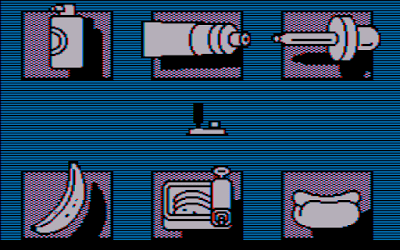

| Players select their hidden item from a menu screen like this one. All other players are supposed to not look. |

|

| Once all of the items are selected, you are told the cost of the items, but not what they are. This helps to narrow down the choices. |

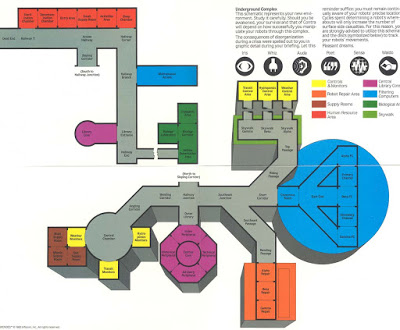

The setting for this item collection is the city of “Fooblitzky”, a cartoon metropolis filled with anthropomorphic animals and insane healthcare costs. We have to snag those items from six types of shops (“Drugs”, “Grocery”, “Hardware”, “Pets”, “Sports”, and “Toys”) which are repeated for each of the four quadrants of the city. We have more than enough money at the start to buy all of the required items, but there are events (such as being sent to the hospital) that cause you to lose money. You can also spend turns working at a restaurant to replenish lost “Foobles” if you make too many purchasing mistakes. In contrast to A Mind Forever Voyaging, there’s no great depth in the city design although it is large enough that keeping track of the location of the 48 key locations is difficult without a map. Fortunately, one is included with the set.

|

| A colorful map of the city. |

|

| The in-game representation isn’t bad. (And two zoom levels!) |

Although the shops are key to collecting the items that you need, there are many other specialized areas that either help with the puzzles or zooms you more quickly around the map:

- A “charity” where you can unload all of your items at once, if you know you have a bad set.

- A “pawn shop” where you can sell unwanted items one at a time, as well as buy items that have been pawned by other players.

- A “restaurant” where you can work to replenish lost coins.

- A subway system called the “U. G. H.” that you can use to zip between quadrants more quickly than walking

- A telephone that you can use to call and see the inventory of any store on the map.

- A pair of lockers that you can put items into and take them out. Unlike the other stores, activities at your locker are private and only you know whether you got something out or what was put in.

The use of the telephone and lockers are a bit subtle, but they add much of the mystery to the game. At the start, the four selected objects will not be located in a store! Instead, your object can be found in one of your two lockers– although you don’t know which one. That means that stores can be “sold out” of an item even at the beginning of the game. If you see a store missing an item and you know that no one bought it, it must be one of the key ones! While you can wander the map to visit each store and find this out, it’s much quicker to call the store by telephone to find out its inventory.

As you wander around the city, you will have to deal with traffic. If you cross the street while cars are coming, you stand a chance of being hit and taken to the hospital. Unfortunately, it can be many turns before traffic patterns change and finding the best route to the store on the other side of town can be an experience by itself. And last but not least, there is the “Chance Man”. If you end your turn without going to a store or other key square, he has a chance of showing up. Sometimes, he gives you an extra turn, but often he takes your stuff and runs away.

With all of those rules (and more!) loaded into your head, it’s finally time to play the game!

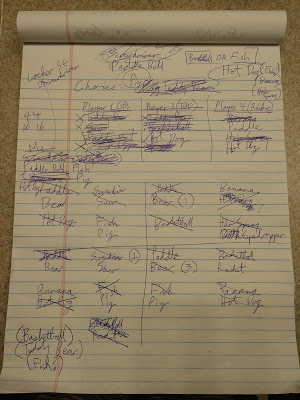

|

| This game requires you to take a lot of notes. |

Playing the Game

In our regular text adventures, this would be the point where I would transition into a first-person narrative of the game. I gave some serious consideration to doing that this time, but narrating my way through a board game doesn’t sound fun for either you or me. Instead, I decided that I would record a game against friends for posterity. I elected to use Youtube for this, although if I were both younger and cooler, I might have used Twitch instead. Blogs about retro video games can only be so cool, right? We can’t hog it all.

The final missing ingredient was the players. Since you need at least two to play (with four computer-selected key items), I solicited our writers and editors at The Adventure Gamer and assembled our roster for our first ever multi-player game. Our three volunteers for this adventure were TBD, Voltgloss, and Reiko. None of them quite knew what they were in for, but I am grateful for their assistance.

Without further ado, I present our playthrough the game (after a brief video introduction). I hope you enjoy it! We’ll wait for you here.

That was quite fun! As you can see, Voltgloss successfully ran circles around the rest of us thanks to his excellent understanding of the mechanics of the game as well as very good note-taking.

For any of you inspired to try this game for yourself: the current version of Dosbox does not support the CGA composite video mode that this game employs. To get the maximum enjoyment out of our playthrough, we used a pre-release (SVN) version of Dosbox, enabled CGA mode, and then pressed the hotkey to enable composite mode. I’ll be happy to provide full instructions if necessary. Multiplayer / internet support was faked by playing through a Webex session using a shared presented keyboard. We successfully played the game from Australia to the United States, so I suspect that is a win all by itself.

Onward to the final rating!

|

| Voltgloss wins! |

Final Rating

Our usual “PISSED” rating scale doesn’t apply to computer board games, but fortunately my gaming companions and I provided some of our thoughts in the video above. You can skip ahead to 1:39 to listen to our thoughts or read the convenient (and cleaned up) transcript below.

Joe: Before we break, I want to loop around the virtual room and have each of you provide some impressions. No set order, but why don’t we do the losers first because your [Voltgloss’s ] opinion will just be wrong. We’ll start with Mr. Dragon.

TBD: I kinda understood what was happening about halfway through when we were playing. It’s very reminiscent of Cluedo, or “Clue” as you Americans like to say. It was fine, but I suspect more of the fun is just hanging around with people one afternoon in my case, or an evening in your case, playing the game.

Reiko: Yeah! This is fun. I think a modern remake might be fun with better icons that you can actually understand and better controls that don’t take ages and multiple, multiple clicks to get working. The concept is fun. Like a board game, it’s something fun to play with friends… just the control scheme is pretty bad.

Joe: I wonder how much of that is just because we’re playing it in a mode that they literally had no way to imagine.

Reiko: That’s true! It might have been easier on the original hardware.

TBD: Yeah, I say most of it is a combination of the connected service, and…

Reiko: I still struggled with the icons though. A modern remake with easier to understand icons and interface would be a lot more fun, but it’s a cool concept.

Joe: The dog is cute!

Reiko: The dog is cute, yeah.

Joe: I liked it. This is honestly the most fun that I’ve had with the three of you… but that might because this is the first and only time we’ve gathered in this forum. As a game that brings together friends to play, it has completely served that purpose. This has been an entertaining way to spend an hour and a half with some folks. I understood enough of it that I was developing a strategy, but I was completely outclassed by someone that took far better notes. I really like the humor here. It clearly doesn’t take itself very seriously. Wait… why does that person have four watches?

|

| You can’t see the watches in this picture, but I promise he has four of them. |

Voltgloss: That’s the Chance Man!

Joe: Is that a bad thing? I don’t quite get it. It’s cute! But it’s also so unlike anything that Infocom did. I can definitely see why this might not have been the success that they were aiming for. It’s a cute game, nice to play with people, and I can’t imagine that I would play this again… but maybe we’ll do a “Championship Edition”. We’ll find some of the old Infocom employees and challenge them to a game of Fooblitzky.

Voltgloss: I’m down for that!

Joe: Volt can be our official nominee!

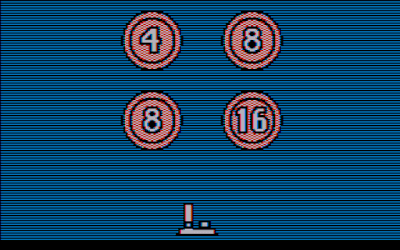

Voltgloss: I’ll happily take that mantle. I like this from a board game perspective. I like the core puzzle here. I do like Clue/Cluedo and its variants. I do think it’s interesting that all information… well, 95% of information… is public. It does make the game… “evolve” is a harsh word, but it feels like it becomes a note-taking exercise. The real meat of the game is in managing the slight bit of imperfect information: knowing what you picked at the beginning of the game and making clever use of the lockers. I’m glad that element is in there; if it wasn’t, then there’d be significantly less strategy space for the game. I like the graphics. I like the dog. I like the “Chance Man”. I don’t like the shopkeepers… Just take out all the humans and leave the “Chance Man” and dogs. There is a lot of luck here. Any game that has random movement up front and center, especially when random movement isn’t between 2 and 12 like rolling six-sided dice, but between one and twenty-something. That gets very swingy. That fact that I won was significantly affected by my getting high rolls generally across the board. There was maybe one time where I didn’t get to where I wanted to go. I got hit by a car once, but I took that chance and it was fine.

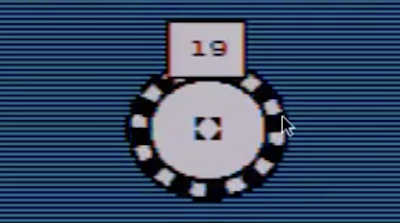

|

| The spinning wheel replaced traditional dice. |

TBD: Did you get hit by a car driven by a different dog?

Voltgloss: I like to think so! I kind of hate the interface. I don’t know why this is a joystick-driven game. I don’t see any reason for it to be a joystick-driven game.

Joe: Keep in mind that it’s not a completely joystick-driven game because you cannot save or quit or do anything else without a keyboard. I don’t even know that we know what all the keys do.

Voltgloss: That’s true. That’s very true.

Reiko: In other words, it didn’t have to be a joystick-driven game.

Voltgloss: I enjoyed it. I enjoyed playing it with friends. Would I prefer to be playing most other board games that I know of with friends? Yes. From a board game perspective, it’s an interesting experiment, but if I owned a hard-copy of this, it would be in my attic and not next to my dining room table.

|

| Voltgloss’s winning collection of notes. He didn’t bother printing the sheet. |

Joe: I want to give you a lot of credit here: you came here the most prepared of us, having had read the manual and understood it better than I did.

Voltgloss: It took me a few tries; the manual is not that well-written as board game manuals go. That’s a key point worth noting: it is unnecessarily dense. I think that’s driven by its interface. It has to spend so much time explaining the icons, what’s a “yes” or a “no”, and what the game means when it gives you a “thumbs down”. Ironically for an Infocom game, this game is hyper-allergic to text.

Reiko: Yes!

Voltgloss: And for no good reason.

Joe: Is there any text in this game, in fact, other than the title and the little status bar on top that says how many “Foobles” you have?

Voltgloss: I think that’s it.

Reiko: Well, it’s funny because on the note-taking sheet it’s got a letter icon for each of the shops, but it uses the little graphical icons in the game. How hard would it have been to put a letter on there? It would have been easier for me.

[…]

Voltgloss: Thank you for bringing us on to do something more fun than Cornerstone.

Joe: I hope we’ll find some excuse to bring us together and play something again in the future, but I agree that this was more fun than Cornerstone. Let’s not talk about Cornerstone ever again…

I want to thank TBD, Reiko, and Voltgloss once again for playing and “reviewing” this game with me. It has been a true pleasure and I almost regret that we do not play more games that have a multiplayer aspect. I have also learned that if one can truly cheat Death by challenging him to a board game, Voltgloss will be immortal. Do not cross him.

And with that, I will close out this review. Before we close out on Fooblitzky, we have one more surprise in store: an interview with lead designer Brian Cody. He has a great story to tell and will be sharing it with us for the very first time. After that, we’ll start into Infocom’s last release of 1985 and penultimate release as an independent company: Spellbreaker. See you in about a week!

A previous version of our video introduction to Fooblitzky featured (by permission) music by Tony Longworth, a musician who produces some fantastic creative commons and other professional music. Unfortunately, in seeking out Fiver help for improving the video, the backing track that I wanted was lost in favor of some other excellent, but more generic, music. Mr. Longworth has an excellent Memories of Infocom album which I recommend for your gaming pleasure. I’m also proud to announce that I am sponsoring (in the name of “The Adventure Gamer”) his Patreon and we are listed on his web site. I’ve learned some valuable lessons in video editing and how not to use Fiver. I hope to revisit Tony and his work in the future as part of an “Inspired by Infocom” retrospective.

Original URL: https://advgamer.blogspot.com/2019/01/infocom-marathon-fooblitzky-1985.html