From The CRPG Addict

|

| There’s no title screen, so here’s the box cover. |

Fame Quest

United Kingdom

BrainGames (developer and publisher)

BrainGames (developer and publisher)

Released 1984 for Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum

Date Started: 7 January 2020

Date Ended: 7 January 2020

Total Hours: 2

Difficulty: Very Easy (1/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

My modus operandi of late has been to write four regular entries and then spin a wheel for the fifth. Today, it landed on Fame Quest, a 1984 British game for the Commodore 64 that I rejected some years ago with the comment “no RPG elements.” Upon re-investigation, it turns out that I was wrong about that. It has, in fact, just enough elements to be considered a “CRPG” under my definitions. It doesn’t have much more.

Fame Quest is the type of game that you’d expect on a cassette magazine, or maybe even a type-it-yourself code list. But it actually retailed independently, on cassette. Its publisher was BrainGames of Brighton, East Sussex, which existed from about 1979 to 1985 and seems to have specialized in simulation games. Those advertised alongside Fame Quest include Election Trail about the American electoral system, Highflyer (“an airline management game”), and Rail Boss, “about the heady days of the Iron Horse in America.”

|

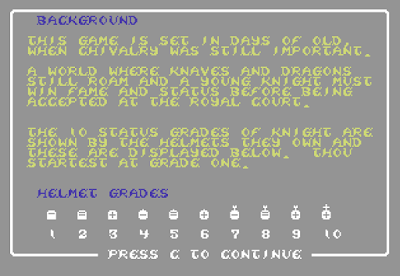

| Fame Quest comes with in-game instructions. |

It plays a little like The Wizard’s Castle (1980) and its variants, though not enough that I’m sure that there was a direct influence. You start it up and without even the ability to name your character, a Grade 1 knight in the king’s castle. You have just enough money to buy a sword and shield. Out the door you go, onto a 9 x 14 landscape of trees, houses, castles, and mysterious encounters. As you explore, you meet other knights, bandits, peasants, maidens, dragons, demons, and other assorted medieval denizens, and you have to decide how to deal with them. If you deal with them correctly and successfully, you get fame points. Once you’ve achieved various thresholds of fame points, you can petition at the castle for a higher grade of knighthood. When you reach Level 10, you’ve won the game. It took me less than 2 hours. It’s good that it didn’t take more than that because there’s no way to save.

|

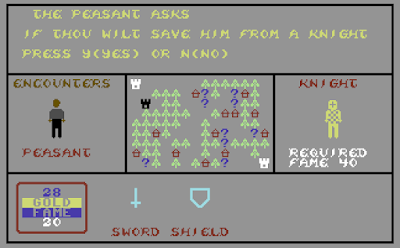

| This is more role-playing than the typical game of the era, I admit. |

The encounters are randomly dispersed on the map, which resets every time you make a new knight level. The encounters include:

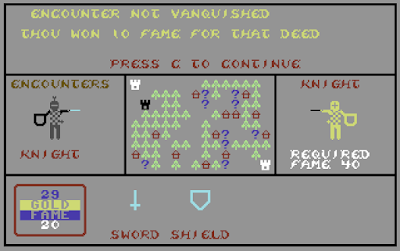

- Another knight. You can talk to him or fight. If you talk, sometimes he has nothing to say, sometimes he asks for a friendly bout. If he says nothing, you fight an unfriendly bout. Some random set of numbers is rolled in the background to determine the outcome. If you win, you have a chance to slay him or let him go. Both give you fame, but if you agreed to a friendly bout, you get more fame by letting him go.

|

| 10 fame for letting a knight live. |

- A dragon, a demon, or a group of bandits. Combat works the same way as with the knight, but you only get fame for killing them.

|

| My knight on horseback charges a dragon. |

- A peasant who begs for money for food. Giving him money increases your fame.

- A peasant or maiden who begs your protection from a knight, bandits, or a dragon. Saying yes takes you to the encounter with one of those creatures.

|

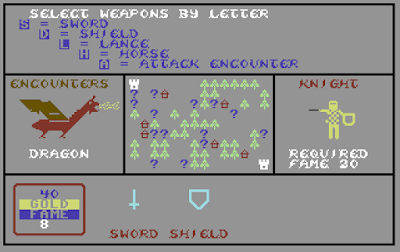

| Selecting my weapons before going into battle. |

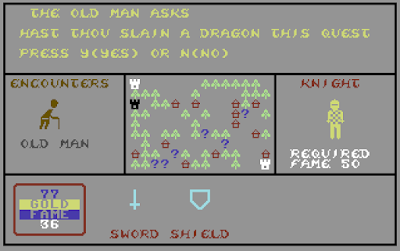

- An alchemist or monk who asks if you’ve slain a demon or dragon this quest. Answering truthfully gives you fame. He might also ask if you need money. If you say no (and don’t), you also get fame.

|

| What if I can’t remember? |

- A king who wants a friendly duel. Letting him live after you’ve defeated him gives you fame.

Losing the battles can lower your (hidden) strength or even result in death. You don’t have many ways to increase your odds, but there are a few. First, you can buy a horse and lance to go with your sword and shield. Second, you can (one time only) pay to sharpen your sword and lance and harden your shield. Increasing your knight level also seems to make you a stronger fighter. After Level 5, I never lost anything.

|

| Death in the game is rare but possible. |

Reaching Level 10 gives you a final screen, and then the game is over.

|

| Yes, those were some amazing trials and hardships. |

That’s about it. There are some “cute” things about the game, such as the way you have to equip your chosen items each combat, and they appear on your little portrait as you do so. The little combat animations, in which you charge a dragon on your steed, or wave a sword at a bandit, are also fun. But it’s otherwise not much of an RPG and it only gets 15 points on my GIMLET, with 1s and 2s in everything.

Because of Chester’s Rule #6 of Computer Games (“Every game, no matter how forgettable, is someone’s favorite”) and Rule #7 (“If that person is a programmer, he will attempt to remake it”), we got a 2006 remake from author John Adams. Maybe I’ll play it in 2036.

|

| The lack of faces disturbs me. |

My goal for most entries is 2,500 words, with a minimum of 2,000. This one is less than 750, so we’ll call it a “half” entry. I’ll find something to write about tomorrow to fill the other half.

****

Dungeons of Avalon II might have be delayed a bit while I work on a technical issue. If the person who is responsible for the “disassembly project” page is a reader of my blog, please contact me offline if you want to help troubleshoot the issue.

****

Dungeons of Avalon II might have be delayed a bit while I work on a technical issue. If the person who is responsible for the “disassembly project” page is a reader of my blog, please contact me offline if you want to help troubleshoot the issue.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/game-350-fame-quest-1984.html