From CRPG Adventures

|

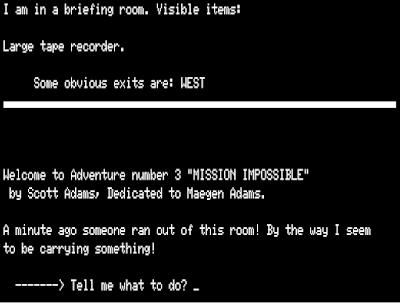

| The opening screen of Mission Impossible |

The screen above shows the beginning of Mission Impossible, the third Scott Adams adventure, and it starts with a bang. Well, relatively speaking; we’re not exactly at the fireworks factory, but by the standards of the era things are zipping along. You start in a briefing room, with someone running away (from you, presumably). There are three obvious courses of action suggested here: check out the mysterious object in your possession, listen to the tape recorder, or follow the person. From a modern perspective it doesn’t seem all that special, but having spent the last few years playing adventure games from the 1970s, this feels propulsive. There’s a sense of action that no game before this one has attempted, and it feels refreshing.

But before I get into the game proper, it’s time to back up and talk about the history a little. I’ve already covered Adams’ previous two games on the blog: Adventureland and Pirate Adventure. I enjoyed them well enough, though both of them were standard affairs, being innovative only because they came so early in the life of home computing. Adventureland in particular was a valiant effort to get something resembling Colossal Cave Adventure onto the TRS-80. Regardless, both games sold well, and it’s probable that by this point Adams was one of the most successful game designers around.

For his third game, he went with a spy theme, and in a blatant disregard for intellectual property rights called it Mission Impossible. In Adams’ defense, the early gaming industry was full of such infringements, and the show was hardly a going concern by 1979. Even so, somebody must have wised him up, because later ports were renamed: it was called Mission Impossible until around 1982, when it was briefly renamed Impossible Mission, until the name Secret Mission was finally settled upon. Also, it was called Atomic Mission on the Commodore 16 and Plus/4 for some reason. These name changes were fairly haphazard; I’ve read that while the title on the front was covered with a gold sticker featuring the new title, the spine remained unchanged, and the disks inside were still labelled as Mission Impossible. Regardless of any later names, in this post I’m going with the original title. The title screen for the TRS-80 version calls it Mission Impossible, so that’s what I’m going with.

|

| The original packaging is not entirely accurate; the saboteur didn’t have a key or a gun! |

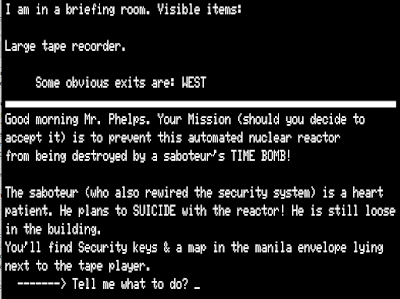

As I mentioned above, the game presents you with three obvious options from the outset. Checking your inventory reveals that you’re carrying a surgically implanted bomb detector, which is currently glowing green to indicate that the bomb is safe. What bomb, you might ask? That riddle is solved by listening to the tape recorder, which plays the following message:

|

| A little more of that good old IP violation. The recorder doesn’t self-destruct, though. |

Okay, so a saboteur, presumably the fellow who just ran away, has set a time bomb to blow up a nuclear reactor. The security keys and map you’ll need for the mission are contained in a provided manila envelope, but when you LOOK around the room the envelope is nowhere to be seen. The game doesn’t draw your attention to this, but it leaves it up to you to draw your own conclusions, the obvious one being that the saboteur has made off with it. It’s a very early example of environmental storytelling, and the game has a little more of that to offer later on.

The area that can be explored outside of the briefing room is small, but it actually comprises almost the whole game. It consists of a central hub, with a Maintenance Room to the west, a room with a strange apparatus to the south, and three colour-coded doors (white, blue and yellow) each monitored by a security camera that demanded I “show authorization” before I’d be able to get through.

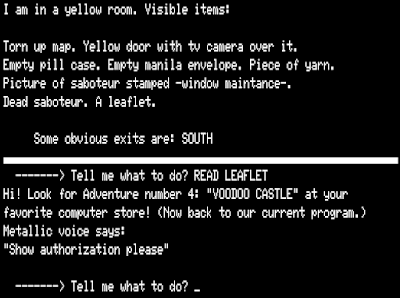

All of the time I was exploring this area the saboteur was running about just out of my reach. At first I worried that catching him might be a time-sensitive puzzle (the kind I hate most in adventure games, just ahead of “all alike” mazes), but I was thankfully wrong. After a while I heard a thump, and found the saboteur’s dead body slumped on the floor near the yellow door. An empty pill case on his body indicated that he had just committed suicide via cyanide capsule.

Also on his person was an empty envelope and a torn up map, no doubt the one I’d been looking for. There was no sign of the keys, but he was carrying the tape recorder, a piece of yarn, a photo of himself labelled “window maintenance”, and a leaflet. The leaflet was nothing more than a cheap plug for Voodoo Castle, Adams’ fourth game, and could safely be ignored, but the rest was sure to come in handy or provide clues to where he might have hidden the keys.

|

| Finding the saboteur’s body |

Still unable to unlock the coloured doors, I went back to the other rooms. In the Maintenance Room I found a bucket, but of much more interest was the apparatus in the south room, a box pointing at a chair bolted to the floor. Sitting in the chair revealed a line of buttons: red, white, blue and yellow. The buttons had keyholes under them, but I figured I’d try pressing them anyway.

I went in order, and discovered that pressing the red button caused my bomb detector to buzz angrily and flash yellow: the bomb had been armed! Pressing the white button right after that activated the box pointing at the chair, which turned out to be a camera. It also disarmed the bomb, at least temporarily. I guess the saboteur had booby-trapped the camera? That’s fair enough, but he really shouldn’t have made it so easy to disarm right after. I’d guess that most people would press the buttons in order, and that’s all I had to do to get this sequence right. If he was really committed, the bomb would have gone off as soon as I pressed that red button.

I left the room, now in possession of a photo of myself stamped “visitor”. After some experimentation, I figured out that showing this photo to the camera on the white door would allow me to pass. (It didn’t work for the blue or yellow doors.) Past the white door was a visitor’s room, with a panel of buttons, a window connected to some red wires, and another camera monitoring the window. Looking through the window (with the EXAMINE command) I could see that I was on the second floor, with the control room of the reactor core below. I could also see a ledge, just outside the window.

The panel had two buttons, one white and one green. The white one simply allowed me to leave the room, while the green one activated a movie projector that was currently empty. Obviously the window and the ledge beyond were of more interest. I tried to BREAK GLASS, and the game prompted me as to what I’d like to try breaking it with. It’s suggestion of my fist was ineffective, so I had a look at my inventory. A picture, an empty bucket and a piece of yarn didn’t sound heavy enough, so I tried the tape recorder. Success! It smashed through the window, falling to the control room below. Unfortunately, the TV camera came to life, and my bomb detector starting flashing yellow again…

Ignoring the warning, I stepped out onto the ledge, where I found some broken glass and a yellow key. My bomb detector was wailing now, but I scooped up the key and tried my best to get it back to the room where I’d had my picture taken. Alas, the bomb exploded before I could get there, and it was back to the beginning.

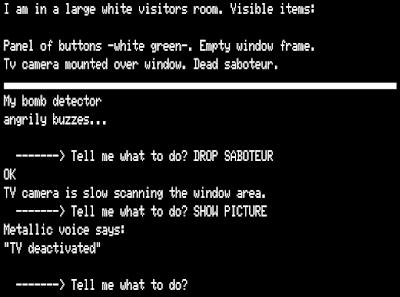

This time, I figured that I should try to identify myself to the camera before breaking the window. The saboteur had a picture that identified him as “window maintenance”, so I took that with me this time. The camera was powered down when I tried to show it though. So I broke the window and then tried it, getting a message that said “owner of badge is not present”. Figuring that a dead face is still a face, I lugged the saboteur’s body into the room and showed the picture again. This powered the camera down, and allowed me to get onto the window ledge without setting the bomb into a countdown mode. I was able to take the key out of the room, use it to unlock the yellow button, and take a picture of myself marked “maintenance”. And once again, taking this picture set my bomb detector back to a safe green level.

|

| Fooling the security system with a dead body. |

The maintenance picture allowed me to pass through the yellow door, which led to another maintenance room. This one contained some wire cutters and an old yarn mop. I pocketed the wire cutters, because I figured I’d be defusing a bomb at some point. As for the mop… remember the piece of yarn I found on the saboteur’s body? That was a hint, and a SEARCH through the mop caused the blue key to fall to the floor. Upstairs there was nothing but an empty movie projector, so there was nothing left to do but head back to unlock the blue button.

This time, unlocking the button and pressing the correct sequence got me a picture marked “security”. The only door left that I hadn’t been through was the blue one, and sure enough my new picture allowed me to pass. Inside was an anteroom, with a door labelled “control room”, a room to the west, and stairs leading up. For some reason I couldn’t open the door, so I looked in the room to the west. In this storage room I found a radiation suit (which I put on) and a vat full of heavy water, which is generally used for cooling nuclear reactors. I figured I’d have to fill my bucket with this stuff for later.

The stairs up lead to a viewing room, with a small window. Looking through, I could see that the control room door was blocked by some debris. Heading back down, I tried a bunch of ways to get the door open. HIT, BASH and PUSH were all ineffective, and I didn’t have anything in my inventory that looked useful. At this point I was stuck, but also pretty eager to get this game over and done with, so I looked up the solution: PUSH HARD was the answer to my problem, and I later discovered that KICK would have worked as well. So I had the right idea, but ran afoul of the parser. Stepping through, I saw that the debris that had been blocking the door was the tape recorder that I had earlier thrown through the window. It’s a nice bit of continuity, but when I read “debris” I was picturing a pretty sizable blockage. I doubt it affected my ability to solve the problem, but it was a bit of a disconnect from what the game described.

The control room had stairs leading down to the core, and a break room off to the east. There was also a sign: “No beverages, please use Break Room”. A seemingly superfluous detail, but those are few when you’re dealing with games with such tight memory restrictions. There was also a film cartridge, which I took back to the empty movie projector to watch. It showed me a safety film about the core, with two relevant bits of information: 1) Plastic deforms strangely in radiation, and 2) Even short exposure to high radiation is lethal, so suit up. I’d already done the latter, so all I had to remember was to not take my bucket into a high radiation area.

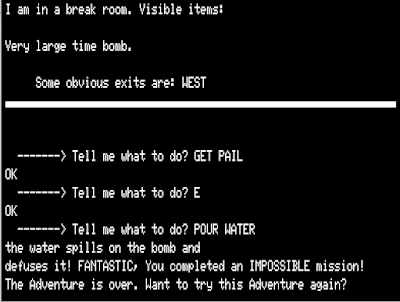

There was nothing left to do except head down into the core. I found a time bomb attached to the reactor by a red wire. I snipped it with my wire cutters, causing my bomb detector to buzz angrily. Taking the bomb, I carried it to where I had left my pail, in the break room. There I put down the bomb, poured heavy water all over it, and it was defused. I had, apparently, beaten an “impossible mission”.

|

| No, it was actually very possible. |

Going into the core without a radiation suit on is lethal, of course, and results in you falling over and retching as the bomb explodes. Taking the bucket into the core is also a bad idea, because it deforms and spills your heavy water. Finally, you can’t defuse the bomb in any other room except for the break room. You can’t actually take the bomb back out through the control room door, so there are only three rooms to choose from anyway, but the break room is the only one that has a floor that doesn’t absorb the water when you pour it.

So that’s Mission Impossible, a pretty simple, small game that nonetheless did some interesting things with the adventure game genre. Firstly, it completely discards the treasure hunt format so popular at the time for something with a more narrative focus. It’s not necessarily the first game to do this, but it’s definitely among the earliest. Of more significance is its use of environmental storytelling: the missing envelope at the beginning, the various items on the saboteur’s body, and the piece of yarn from the mop in particular, are examples of this kind of thing. I’m not playing the games from 1979 in a strict chronological order, but regardless of whether another game got there first, Mission Impossible is still doing it in 1979, and that has to count for something.

That said, the story it’s telling, aside from being a complete knock-off of a popular TV show, doesn’t exactly hang together. The saboteur’s plan is the main culprit here, as his various booby traps are pretty nonsensical, obviously designed to be puzzles from an adventure game rather than actual traps a real saboteur might set. Yes, I get that criticising a game for having unrealistic puzzles is a little absurd, but the closer to the real world a game’s setting tries to be, the more it invites this kind of criticism.

And now, to the Final Rating.

Story & Setting: The setting for this is a novel one, but it’s not all that convincingly realised, being little more than a series of coloured doors to get through. That’s no doubt a consequence of the hardware, but I gotta rank what’s there. As for the story, it gets some extra points for novelty and environmental storytelling, but it’s still too simplistic to rank high. Rating: 2 out of 7.

Characters & Monsters: There are none, aside from the saboteur who commits suicide right at the start of the game. You’re never able to occupy the same area as him until he’s dead, and his body is even used to solve a puzzle, so he’s much more of an inventory object than a person. Rating: 1 out of 7.

Aesthetics: It’s a sparsely-written text adventure on the TRS-80, what did you think it was going to get? Rating: 1 out of 7.

Mechanics: It’s the same two word parser that Adams has been using since his first game, and even at this point it’s starting to feel a little long in the tooth. I had one “guess the verb” problem, which I probably shouldn’t dock it for, but I’m feeling ever-so-slightly uncharitable right now. Rating: 3 out of 7.

Challenge: I’d say this game is a little too easy, even though I consulted a walkthrough to beat it. That took me about an hour, and I’m pretty confident that I would have sussed out the answer without too much time on top of that. It’s certainly Adams’ easiest game yet, so I can’t rank it high. Rating: 3 out of 7.

Innovation & Influence: This should get some points for being an early Scott Adams game, as well as for its storytelling innovations. It might seem simplistic now, but I haven’t played anything else for the blog that had done this kind of thing before. Rating: 4 out of 7.

Fun: The main advantage this game has in this category is that I finished it really quickly. On the other hand, I consulted a walkthrough so that I could finish it more quickly, which I think says something. It didn’t elicit any negative feelings in me, but I wasn’t exactly having a blast with it either. Rating: 2 out of 7.

I won’t play Mission Impossible again, so it doesn’t get the bonus point. The above scores total 15, which doubled gives a Final Rating of 30. That put’s it 23rd out of 33 games played, and 12th out of 19 adventure games. It’s equal on points with Greg Hassett’s Voyage to Atlantis as well as Colossal Cave Adventure II. Both of those are better games, but the former lacks Mission Impossible’s interesting points, and the latter is full of hella annoying puzzles.

NEXT: I’m sticking with the TRS-80 to play Atlantean Odyssey, which has a decent claim to being the first ever fully graphical adventure game. Eat that, Roberta Williams!

Original URL: http://crpgadventures.blogspot.com/2019/11/game-33-mission-impossible-1979.html