From The CRPG Addict

|

| The castle ramparts depict all of the different enemies in the game. |

Swords and Sorcery

United States

Independently developed in 1978 on the PLATO mainframe at the University of Illinois

Date Started: 28 January 2019

Date Ended: 30 January 2019

Total Hours: 7

Difficulty: Medium (3/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at Time of Posting: (to come later)

We’ve had a look at several PLATO games over the years, and most of them fall within two branches. The first is the single-character iconographic maze-crawler, represented by The Dungeon, The Game of Dungeons, and Orthanc, all originally released in 1975. The second is the multi-character, first-person sub-genre, represented by Moria (1975), Oubliette (1978), Avatar (1979), and Camelot (1982). I’ve at least dipped into all of these except for Camelot.

|

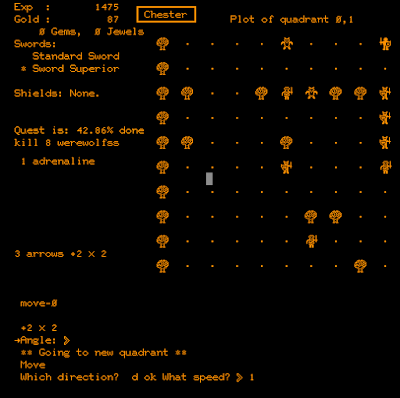

| Swords and Sorcery has you navigate a series of map grids with monsters, treasure chests, and obstacles. |

But in my survey, I overlooked Swords and Sorcery, which owes its lineage to none of these other titles. Instead, it is a variant of the prolific Star Trek, written originally by Mike Mayfield in 1971 on his California high school’s SDS Sigma 7 mainframe. From there, he ported it to several other systems, and it became so popular that variants of the game began appearing in books of type-it-yourself game code. A decade later, it was tough to find a computer system that didn’t have some version of it. PLATO has one, under the lesson name trek.

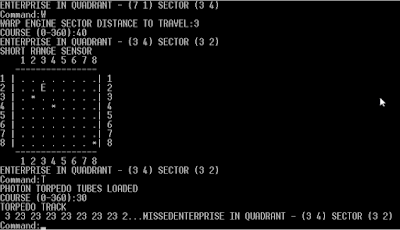

Star Trek featured gameplay on a gridded star chart, with 8 x 8 quadrants, each quadrant divided into 8 x 8 sectors. The player piloted the Enterprise through these various sectors, tried to complete his mission to destroy 17 Klingon vessels, and found refuge at the occasional starbase. Stars served as obstacles to navigation and combat.

|

| Gameplay in Mike Mayfield’s Star Trek (1971) took place on a tactical grid. |

Swords and Sorcery is a fantasy adaptation of this basic idea. The character gets quests from a king rather than missions from Starfleet. Instead of Klingons, he contends with orcs and goblins, and instead of phasers and photon torpedoes, he fights with a sword and arrows. The tactics associated with positioning and movement are otherwise all present, with trees taking the role of stars in the earlier game.

But Swords‘ developer added some elements that qualify the game as an RPG in the way that its science-fiction predecessor did not. First, the character is persistent. He doesn’t “win” upon killing 17 enemies, but rather turns in the quest for a reward and then gets another. He gains experience, earns gold, finds items, and retains these things between quests. And the quests themselves vary, with the player able to specify the size of the overall game world and thus (to some degree) the quest difficulty.

|

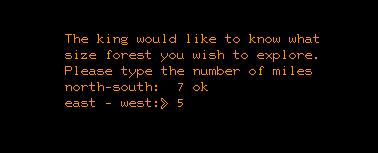

| Creating the game world. |

“Character creation” is just a matter of specifying a name. Characters start with a regular sword and nothing else–not even any hit points. As the first mission begins, the player determines the size of the game world, from 1 x 1 to 10 x 10. This in turn determines how many enemies you face, treasure chests you have to open, and safe “magic circles” you can visit.

The first mission is usually just to chop down trees, the specific number dependent on the number of quadrants in the game world. Sometimes you get treasure-collecting missions or monster-killing missions as the first one. Tree-chopping never occurs after the first mission, which is merciful. Game begins in a random quadrant within the world you created.

|

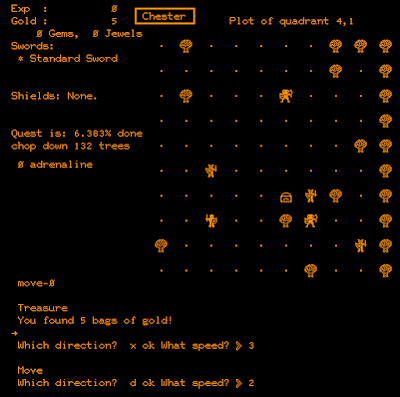

| An early-game mission on a small map. |

The most difficult moments are the opening ones. Experience points are the same as hit points, and you have none of either. Monsters will kill you in one hit if they get adjacent to you. You spend these early stages avoiding monsters rather that engaging them. It takes some experience before you get a feel for how quickly monsters can close the distance, and thus how much room you have to play with on a given screen.

One of the oddities of Swords is the movement system, which works like it did in Star Trek but makes less sense than it did there. You specify a direction and “speed,” which is the number of squares you move in one turn. You can choose between 1 and 3. Finding or buying adrenaline phials lets you crank it up to 4. Once you assign these variables, you’ll keep moving that direction and speed each round (after whatever other action you take) until you change it or hit “0” to stop entirely. So if one round brings you adjacent to a creature and you choose to attack him on the next round, you can do that, but then you’ll continue sailing past your foe whether you kill him or not. If you run into an obstacle, you’ll take damage and stop. Any damage is enough to kill you at the beginning of the game, so until you get a feel for the movement system, a lot of your characters will commit suicide by running into trees.

|

| This happened to me a lot in the early game, too. |

To survive, you need to find treasure chests. These may contain arrows, which will allow you to kill enemies and build experience at range, or they may contain gold, with which you can buy arrows or experience at magic circles. Rarely, chests will contain magic items like improved swords, shields, armor, boots, and adrenaline phials.

|

| Until you start opening chests, you don’t have many options. These 5 bags of gold will now allow me to buy experience (and thus hit points) or arrows. |

Finding chests isn’t as hard as reaching them without encountering any monsters on the way. Fortunately, while the quantity and type of contents on a screen are fixed, the distribution changes every time you leave and return. So if you arrive on a screen to find a treasure chest on the opposite side with four goblins in between, you can pop off and on the screen, and hopefully the next time you’ll find a better arrangement–specifically, one where you can avoid the goblins long enough to reach the chest.

Once you have some arrows and understand the movement system, it’s not hard to keep enemies at bay and kill them from afar. Some arrows have damage multipliers that let you kill more than one enemy along the same trajectory. Once you gain a few hundred points of experience, you can engage enemies in melee combat without worrying about instant death; fighting is just a matter of specifying (S)word and then a direction, the only real “tactics” being the use of movement and terrain to ensure you strike first and don’t get surrounded.

|

| I’m in the upper-right corner. The three goblins lined up to the south will fall to a single arrow, leaving just the zombie at their tail. |

“Magic circles,” of which there are about one per four screens, serve in the role of the “starbase” in Star Trek. Monsters can’t attack you while you stand in them. You can sell gems and jewelry that you’ve found and buy arrows, swords (as replacements for those that break), and adrenaline. You can also spend money directly on experience points.

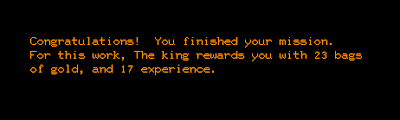

For the tree-chopping quests, I found it easiest to clear out the enemies first, then walk along the border, hewing a tree every step. For monster-killing and treasure-finding quests, you generally complete them as you naturally explore the maps. When you’re ready to go home, you enter one of the magic circles and hit “q.” You’re transported back to the castle and the king gives you gold and experience as a reward. From there, you just hit ENTER to create a new map and get a new quest.

After those initial difficult stages, the game becomes a bit too easy. I played several characters, and if they survived the first quests, they had enough money to keep a large stock of arrows and continue building experience and health. Subsequent missions introduce tougher creatures like werewolves, zombies, wizards, and dragons (along with quests to kill n numbers of them), but their difficulty doesn’t keep pace with your own character development unless you get lazy or sloppy.

|

| In my second quest, I face werewolves, zombies, thugs, and goblins in the same screen. It would be smart to just leave to the north rather than fight them all. |

One way to force a greater level of difficulty is to create a map of 1 x 1. This leaves you nowhere to run. While your quest will be easier quantitatively (e.g., killing one dragon instead of seven), it will be functionally harder because you’ll have to clear out all enemies on the confines of a single screen.

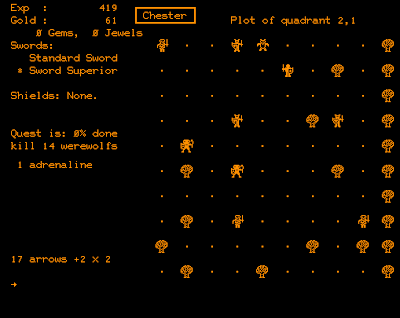

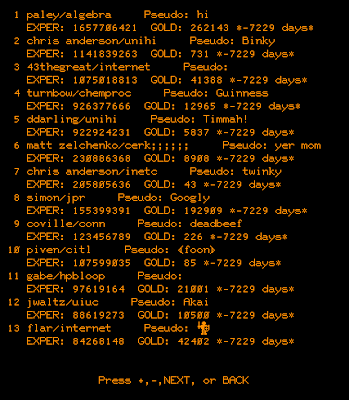

Some people must either like the relative ease or find other ways to make it challenging, because the player list shows 31 players who have each amassed more than 1 million experience points in the 18 years since the game was last reset. The top player, with a user name “paley” and a character name of “hi,” has about 1.66 billion experience points. The creator has a character named “goodgulf” with 776 million. Dirk Pellett, one of the authors of The Game of Dungeons, also seems to be a fan: his “Aumkua” has 16 million.

|

| Part of a list of rabid devotees. |

Swords and Sorcery was written by Donald Gillies, who first alerted me to its existence in an e-mail. He was a student at Urbana High School, which had access to PLATO, from 1976-1980. Swords was based on a previous title that went under the lesson name think15 before it was deleted by system administrators. Gillies credits the author of that game, Jim Mayeda (a fellow UHS student), on his own title screen. (In between the two, another student’s attempt to replicate think15 as think2 was also deleted.) Gillies wrote a first draft in 1977 but says it only included fighting; the full version was finished in the spring of 1978. By 1980, it was the seventh most popular game on PLATO at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Gillies–who went on to an undergraduate education at M.I.T., a doctorate at the University of Illinois, and a career as a software engineer in the private sector–kept a printed copy of the source code and re-typed it when Cyber1 resurrected the PLATO system in 2003.

For no particular reason other than I had the time, I chose this game to create a video review, which you watch below or on YouTube. This is the first video I’ve narrated in about 5 years, and I tried to introduce some “production values” that will naturally improve as I gain experience. I’m happy to take recommendations on my approach to videos.

Swords and Sorcery is left off most lists of the classic PLATO RPGs, so I’m glad Dr. Gillies wrote to me, and I’m glad I had a chance to experience his game’s unconventional approach. In the coming months, we’ll have at least one more PLATO entry covering the last of its RPGs: Camelot (1982).

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/02/game-318-swords-and-sorcery-1978.html