From The Adventure Gamer

Written by Joe Pranevich

After a birthday detour back into Infocom-land, I’m back to playing Consulting Detective. Last time around, I solved the first of three cases by finding a lion-murdering thief with a penchant for poisoning his witnesses. That case was pretty fun but not perfect. It did take me a bit to get back into the swing of things this series and I could have solved it faster if I had done a better job with the newspaper and remembering to use my “Regulars”. I’m going to jump into this second case more prepared and see if I do any better.

This time out, we are solving the case of the “pilfered paintings” and the case starts with a proper introduction video. Sir Simpson Witcomb, a well-dressed older gentleman, seeks Holmes’s help in the recovery two “De Kuyper” paintings taken from the National Gallery. Six months ago, two previously unknown paintings by the artist were discovered and auctioned at Armitage’s Gallery. De Kuyper, we are told, was a student of Reubens, a Flemish master and someone even I have heard of. Prior to this auction, only six De Kuiper paintings were known to exist: four in the Louvre in Paris, one in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and one by a private collector, Lord Smedley, in London. Witcomb worked with his head curator, Brady Norris, to acquire the two newly discovered works and add them to the National Gallery’s collection. They were able to snag them for a mere £125,000, far less than expected.

With the National Gallery in London now home to one-fourth of the known De Kuyper paintings, Witcomb set his sights on the first ever expedition of all eight known works. That would have opened tomorrow, if not for the theft of two of the paintings. As such, all of the other works are also in London ready to be moved to the Gallery: the Louvre’s four are stored in the French Embassy, the Rijksmuseum’s one in a separate National Gallery storeroom, and Smedley’s still at his townhouse. With that helpful information, we are off to solve this case!

|

| The newspaper interface is okay, but not great. |

Just because I am curious, I did some research on sales of art. I have no idea what art sales were really like in the 1890s, but the £125,000 back then equates to around $725,000 in modern US dollars. That is a large sum, but tiny compared to the millions that art from masters of the period sell for. I also happened to notice that the introductory video appears to have a scripting error: Witcomb clearly states that there were six known paintings before the new ones are discovered, but Holmes later asks only about where the “other four” paintings are (implying a total of six). Either our detective friend lost track of how many paintings were out there, or the scriptwriters did. I doubt that will be too pertinent. That would strike me as unimportant, except the manual and video also do not agree as to the date of the case: the manual says Jan 22, 1891 while the newspaper and video say Jan 1, 1891. However, the lack of any mention of “New Year’s Day” in the videos or newspaper, suggests that the 22nd date is more likely. Again, it’s not a huge deal but it hurts to start a case by noticing errors.

Speaking of newspapers, I search them to see what I can find. The common “abandonware” manuals out there on the web for this game have an incomplete set of newspapers and are missing the dates needed for this case. I have since ordered two copies from Amazon, but neither of them came with the original newspaper either. Fortunately, there is an “in game” newspaper which we can use, but it is impossible to search or skim. I may miss something because of this.

The juiciest details are scattered across a few issues:

- June 9, 1890 – Armitage announces the sale of newly discovered De Kuyper paintings; auction to be held on July 1 at 1:00 PM.

- June 26, 1890 – Everett Sedwick responds in an op-ed to a previous (not included?) article about Reubens at the National Gallery. He says that Lord Thurlow is correct about how many of his works are in the Gallery, but that he is otherwise an amateur. He corrects him on the spelling of one of the paintings (“Chapeau de Peil” instead of “Chapeau de Paille”). Sedwick compliments the paper’s usual art editor, “H”, for knowing his (or her) stuff.

- June 26, 1890 – Armitage re-runs the same ad from the 9th.

- January 1, 1891 (“Today”) – Sir Simpson Witcomb announces his retirement from the National Gallery, effective in June. Coincidence?

- January 1, 1891 (“Today”) – A thief steals two De Kuyper paintings, “Summer Solstice” and “Blue Unicorn”, shortly before midnight.

There is a lot to take in here, but already my mind is racing. What if the two new paintings are forgeries? Could the whole auction and expedition be a way to flush the other six paintings out into the open? If so, why weren’t they stolen? There was a third even in the Gallery that was passed over! Could Lord Smedley be upset that the value of his paintings are decreased now that there are two more? Does the lower-than-expected cost at auction come into play somehow? We’re going to need to start talking to people and I’m going to reach out to Smedley first.

|

| Not the master manipulator I was expecting. |

My theories about Smedley seem to be off base immediately. Rather than a criminal mastermind, he’s a doddering older gentleman wearing a huge white corsage, yet another bumbling British aristocrat. He tells us that he bought his De Kuyper from a Dutchman many years ago, after being alerted to the sale by “Mr. Donet”. He doesn’t even know the Dutchman’s name! Thanks to the burglary, he’s moved his painting to the vault at Cox and Company until the situation is resolved.

I am immediately suspicious that he doesn’t know the name of the guy that he bought his painting from, but he was working through a middle-man. I’m struck with the idea that his painting could be a forgery as well… or perhaps all of the paintings are forgeries? It’s tempting to say that, but someone must have benefitted from the theft so we have to assume they were all valuable.

|

| Everyone in this game has such nice suits. |

While Smedley was alerted to his sale by Mr. Donet, someone that we do not know, Witcomb was told about his by Brady Norris, the National Gallery’s head curator. That would seem to eliminate him as a source of suspicion immediately, but it’s worth a discussion if he can shed light on the paintings’ origins. Unfortunately, he doesn’t know about the crime because he was at Dame Agnus’s dinner party last night when the robbery was happening. He claims to have no theories about the thief or how he (or she) could have pulled off the heist. He also explains that the National Gallery has many more expensive paintings than those, none of which were taken in the crime. It’s clear that the thief was specifically targeting only those two paintings (and either was unaware or unable to access the third in the storeroom).

There is no “Dame Agnus” in the London directory so I’m going to move along from that line of inquiry for now. Next up, I’ll talk to one of my “Regulars”, Langdale Pike the society gossip columnist.

|

| That must have been some party! |

Mr. Pike turns out to be a better choice than I expected! I had hoped that he could tell me more about Dame Agnus, but he was at the same party that Norris had been and was even nursing a hangover! While he cannot tell me too much because of his incredible headache, I learn about Pierre Donet, the world’s foremost expert on De Kuiper. Only two decades ago, Donet was a starving artist but thanks to his fortuitous discovery of the very first De Kuiper painting in a church in Brussels, he is now living the high society life. That first painting was sold to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. We know from Lord Smedley that he also helped to sell him his painting some time later. Donet is presently staying in a “luxurious suite” at the Langham Hotel. Very curiously, Pike adds that despite getting his start as an artist himself, Donet has never sold a single one of his own works.

Suddenly, this all seems too obvious. My note earlier that all of the paintings might be forgeries was prescient. It’s clear to me that Donet is a forger twice over: not only has he been creating and selling fake De Kuiper paintings, he likely also invented the artist himself. It’s also possible that the first painting was real, but what’s clear is that he’s spent twenty years living off the proceeds from the sale of only six paintings. The two new paintings did not sell for as much as he hoped for; is it possible that he stole them to increase their value? That seems like a stretch. It is more likely that his crime is completely separate from the thefts. Why would someone steal the two new paintings? If they knew they were forgeries, why bother? If they didn’t know they were forgeries, why just those two and not the third? Or any other painting in the museum? I have no idea yet.

|

| Seriously, everyone dresses so well… |

As Mr. Donet is from Belgium, we don’t find his name in the directory, but we do have a listing for the Langdale Hotel. (It’s listed under “H” for “Hotel” for some reason.) We meet him in what appears to be a hotel restaurant and chat over a nice bottle of wine. He claims to have just arrived from Brussels yesterday. More importantly, he tells us about the two paintings that were stolen: he does not know who found them or how they ended up at Armitage, but he was brought in to evaluate the works and sign the certificate of authenticity. Mr. Noir, a Brussels lawyer representing his anonymous client, witnessed the signature. He then saw the paintings for the first time the following day, in Nori’s hotel room. I’m immediately suspicious because he signed the certificate before examining the paintings, although he claims to have spent five hours confirming them the next day. He tells us that the brush strokes, signature, and even type of canvas used all point to the two new works being legitimate De Kuipers.

He’s clearly lying since he signed the certificate before seeing the works and this adds credence to the idea that he’s the forger. I’m just less and less convinced that he’s also the thief. Even if he was trying to increase the value of the remaining paintings, it’s a lot of hoops to jump through if he could just knock out a few new works every couple of years to stay afloat.

|

| This is the “are you some sort of idiot” scene that I see so often. |

Even as I feel I’m getting close to the answers, my next moves are all missteps. I still have no lead on Dame Agnus to confirm whether Norris or anyone else left the party early. Everett Sedwick, the expert on Reuben from the newspaper, seemed like a good person to talk to I am only told that he is “chatty” but unhelpful. I revisit Sir Simpson Witcomb from the opening cinematic to see about the painting that he has stashed in the National Gallery basement. In what must be a script error, I also get a message saying that he is “baffled that we had come” and “has no idea about our case”. This case has a higher than usual number of errors.

|

| What a suspicious package! |

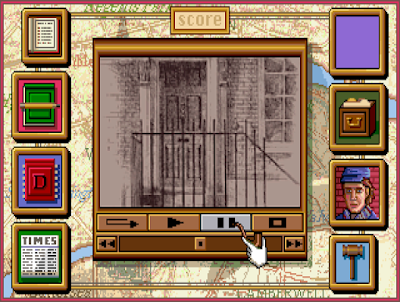

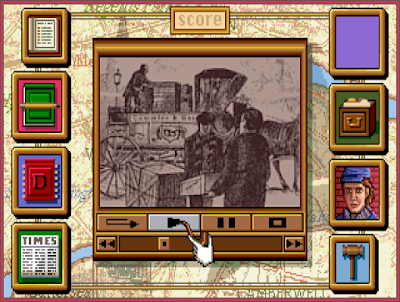

If Witcomb doesn’t tell me about the painting in the storeroom, I can go directly to the National Gallery. That is the scene of the crime anyway so a good place to look for clues. That reveals an amazing interview with one of the four on-duty guards from the time of the theft. He lays out a timeline of the whole evening:

- His shift started at 4:00 PM, prior to the Gallery’s closure. His first job is to prepare for the closing an hour later. At 5:00 PM, the Gallery closes.

- By 5:15, all of the employees left except from Witcomb and Norris. That was typical since they liked to ensure the gallery was secured every night.

- Witcomb left from the main entrance at 5:30, but Norris stayed as he was expecting a delivery.

- At 5:45, a set of three packages arrive for Norris from “Cummins and Goins”: one large crate and two smaller ones. The guard observed that the smaller crates were from Jardins, but he did not observe the origin of the larger one.

- As soon as the delivery men left, a guard named Charley barred the door. Norris remained to inspect the packages.

- At 6:30, Norris locked the storeroom and left for the evening. He was let out the main entrance. The guards resumed their regular rounds.

- At 11:10, the guard observed that all paintings were still in place.

- By 11:35, the two De Kuipers were gone, cut from their frames.

- While Norris and Witcomb have keys to the interior doors, they don’t have access through the external doors. Only the guards and the guardroom has those keys.

That is a ton to chew on, and I wish that I had gone here first! Three crates is suspicious, especially with two of them smaller than the other. I suspect that someone was hiding in the large crate and would box up the paintings in the little ones to ferry them safely away. Who? I don’t know, but this seems like a plausible way for the thief to get into and out of the building without being detected. I am still missing a motive however for why someone would go through all that trouble for two low-value paintings.

|

| That mustache did it. |

Who sent the boxes? Let’s track them back to their sources.I go to the shipping company and speak to someone behind the counter. He confirms that the packages were mailed from Mr. Norris to himself at the museum. The shippers picked them up from Well’s Warehouse at 5:30 PM, arriving at the Museum in an hour. That’s all we know, but it is plenty. I check the warehouse next to learn that it was rented out by someone named Matthew Cole until recently; someone (he doesn’t say who) rented it starting yesterday. That cannot be a coincidence!

Who could have been in the crate? Not Norris because he was at the museum, nor Witcomb since he left at 5:30 and could not have made it to the movers in time to sneak in. Who is left? Donet? I still don’t have anyone with a motive.

|

| What the heck? |

My final stop is Disreli O’Brien, the clerk at the hall of records. I hope to discover who rented the warehouse after Matthew Cole, but I get more than I bargained for. For some reason, Watson asks him about some guy named Clifton Maddox. He’s a former art gallery owner who was arrested in 1889 on suspicion of stealing a Turner painting from Sir Charles Chandwick. That sounds like useful information, but this is the first that I am hearing about it. Is that a false lead or am I going to discover that Chandwick is the other accomplice?

With that, I am wrapping up for the night. I still have no motive, but I am fairly sure that Donet is a forger and Norris is part of the theft. But where are the paintings now? And how will I solve this case? I expect we’ll find the answers soon enough. Please feel free to share your theories (please do not comment if you know the answer) below. See you next week!

Time Played: 2 hr 05 min

Total Time: 5 hr 25 min

Original URL: https://advgamer.blogspot.com/2019/10/consulting-detective-vol-ii-pair-of.html