From The CRPG Addict

|

| Crystalware was not the sort of company to let trademarks deter them, whether incorporating the Enterprise in their logo or marketing an unlicensed game called Imperial Walker. |

A year ago, I’d never heard of Crystalware. Then, someone rediscovered their catalogue and uploaded all of its games to MobyGames and my year became in large part about the company. But let’s face it: none of its games are really RPGs. They have some RPG “elements” in some of the inventory selections and random approach to combat, but there isn’t a single one in which the character grows intrinsically from his experiences except for The Forgotten Island (1981), and that was a basic “power” statistic whose rapid growth made the game fundamentally too easy.

Most of Crystalware’s games instead occupy a strange subgenre that we might call “iconographic adventure.” Most adventure games are either all-text (Zork) or made up of graphically-composed scenes. Sometimes, the scenes offer a kind-of first-person perspective (Countdown, Timequest), and other times they feature the character in a kind of side-view perspective that I’ve taken to calling “studio view” (King’s Quest, Leisure Suit Larry). I’m sure there are adventure games with axonometric perspectives, although none come to mind. But something about a top-down iconographic interface screens “RPG!” even though there’s no reason adventure games couldn’t feature the same perspective. That’s really what Crystalware games are. They involve finding inventory items to solve puzzles and often escape a situation. Only a couple offer character attributes and none offer character development.

I’ve been gamely trying them anyway, but the last few have been giving me trouble, and I’m not going to continue wasting a bunch of effort for titles that aren’t RPGs in the first place. I’m going to reject or “NP” the rest and suggest that MobyGames, which also cites character development as the primary mechanism for RPGs, remove the RPG designation although keep “RPG elements” under its gameplay elements.

|

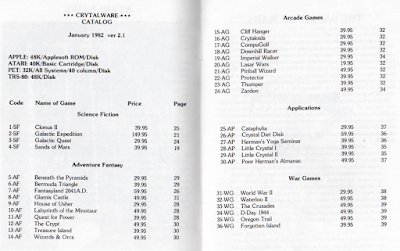

| Crystalware’s catalog in late 1981. |

As we’ve seen, Crystalware was a remarkably high-quantity (if not high-quality) company for its brief 1980-1982 existence. Within those three years, they developed and published the following titles, not all of which are even on MobyGames:

- The House of Usher (1980)–also the name of the pop artist’s inevitable reality show–is a Gothic adventure based on the Poe story of the same name. I reviewed it in June 2019.

- Labyrinth of the Minotaur (1980): Set on Crete. I haven’t been able to find much about the game, but it’s attested in their 1982 catalogue.

- Sumer 4000 BC (1980): A text simulator in which you’re the King of Sumeria, trying to manage resources and make your empire survive another year.

- Galactic Quest (1980): A space combat and trading simulator.

- World War III (1980): A strategic wargame for two players, one fighting for Iran, the other Iraq.

- Beneath the Pyramids (1980): An adventure game in which you explore some weird combination of the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid at Giza for an artifact. I reviewed it in June 2019.

- Waterloo II (1981): A two-player wargame in the Napoleonic Era.

- CompuGolf (1981): A golf simulation.

- Imperial Walker (1981): An unlicensed action game in which an imperial walker commander tries to shoot down rebel craft. (I think it really says something about the company that they conceived of such a game and made the imperial the protagonist.)

- Laser Wars (1981): An action game in which you defend a city from alien attackers.

- The Sands of Mars (1981): An adventure game in the style of Oregon Trail, in which you assemble a crew, purchase supplies, and try to make it to Mars and back. This one was categorized as an RPG. I tried to play it but couldn’t get past a takeoff procedure that required the Apple II paddles. (Multiple sites say that AppleWin emulates paddles, but I’ll be damned if I can figure out how.) The manual doesn’t make it sound like it has RPG elements. It suggests that there are multiple phases of the game, each involving a different interface and style of gameplay.

|

| As far as I can get in The Sands of Mars. |

- Forgotten Island (1981): An adventure game where you escape an island. It was renamed Escape from Vulcan’s Island when re-issued by Epyx. I reviewed it in October 2019.

- Oregon Trail (1981): Some version of the classic.

- Quest for Power (1981): An adventure game in which you try to prove your right to inherit Camelot from King Arthur. It was re-issued by Epyx as King Arthur’s Heir. I reviewed it in March 2020.

- Protector (1981): An arcade game in which you fly a ship through caverns.

- Fantasyland 2041 (1981): An epic multi-disk adventure game based on Fantasy Island. I reviewed it in October 2019.

- Dragon Lair (1981 or 1982): As attested in this Hardcore Gaming 101 article, perhaps the first RPG in Japanese.

- The Bermuda Experience (1982): An adventure game in which you have to navigate a ship around the Atlantic Ocean in several time periods. It is also known as Bermuda Triangle.

- Treasure Island (1982): An adventure game in which you explore the Caribbean for map pieces.

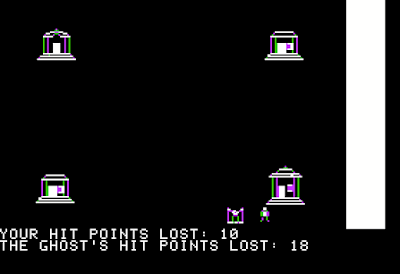

- The Crypt (1982): An adventure in which you must survive the night in a cemetery. This was also designated an RPG by MobyGames, and I tried to play it but ran into a bug where neither you nor an enemy ever dies in combat. Instead, the game happily takes you into the negative hit points as you pound away at each other round after round. Thus, the first combat you get stuck in ends the game. It otherwise had the same characteristics as other titles that I reviewed that weren’t really RPGs. It was re-released by Epyx as Crypt of the Undead.

|

| Combat among crypts in The Crypt (1982). |

- Zardon (1982): An action game where you fly a ship, blow up enemy ships. This one was re-released by Avalon Hill after Crystalware folded.

- The Haunted Palace (1982): An adventure game with RPG elements in which you try to solve a mystery. You can choose among characters who have RPG-like attributes but they never grow. It was re-released as The Nightmare by Epyx.

- Clonus (1982): An adventure game in which you navigate the future as a clone with cyborg parts. A near-immediate Clonus II seems to be a re-release of the original rather than a true sequel.

They also released two compilations of simple games like Hangman and Tic-Tac-Toe for kids, a diet planner, a yoga instruction program, a garden simulator, and a program to help cat owners diagnose illnesses in their pets.

Almost all of the company’s games were written for the Apple II, Atari 8-bit, and TRS-80. The company principals, John and Patty Bell, contracted a team of programmers who sometimes wrote original games, sometimes spent their time porting games created by others. About half of them were created by the Bells themselves. Almost all the adventure games hinted at a deeper mystery beneath the surface of the game and offered a cash prize to whoever was the first to solve it.

|

| By 1981, the company was putting out a quarterly newsletter. |

With each game costing $39.95 and up, Crystalware must have been doing well even if they only sold modest amounts. But that’s nothing compared to the company’s plans. A company newsletter from late 1981 shows that future offerings would include Glamis Castle, a three-dimensional adventure game in which you could explore the famous Scottish landmark, an RPG based on Lord of the Rings called Wizard and Orcs, and an epic hub-and-module adventure called Galactic Expedition. Each module would sell for $29.95 and contain the ability to explore a different planet or moon.

Oh, but that isn’t nearly all. The company was planning to release a series of home-schooling programs based on the “Crystal Theory of Alternative Education” (CTAE). They were working with Universal Pictures to provide realistic computer program “props” for an upcoming film called The Genius (it seems to have never been filmed, although the associated producer, David Sosna, is a real person). They were working on the first “videodisk fantasy” for the PR-7820-2 Videodisc Player from Discovision. They were starting a “lonely hearts club.”

Best of all, Crystal Films was being born! They had a named producer, script supervisor, costume designer, and key grip on their masthead. They had three productions in the works: Haunted (a horror film), Fantasyland (based on the game), and Sarah, about the life of the eccentric Sarah Winchester, who built that sprawling monstrosity of a house in San Jose.

|

| Apparently, Haunted was to be filmed in an actual haunted house, not just a set that they made appear haunted. I guess that’s one way to save on special effects. |

The newsletter, in short, feels like it was dictated by someone in the middle of a manic episode, and what happened to Crystalware next suggests that it all came crashing back to Earth. I haven’t been able to find an official, comprehensive account of the company’s last days, but we can piece it together from evidence. First, I have an anecdotal report from a reader who owned a computer store in the area at the time, saying that Crystalware’s finances were essentially a giant house of cards and someone was destined to lose. To clarify, I don’t think the Bells were deliberately scamming anyone. One programmer I spoke to, Henry Ruddle, said that the company always paid him well and on time. Another, Mike Potter, has posted online that Bell fired him when he questioned his royalties, but did pay him and also gave him back the rights to one of the games he’d developed. The issue is more that they seem to have been leveraged beyond a sustainable debt.

We know that in 1982, Bell sold the rights to his games to Epyx, which re-published them, often under different names, with absurdly elaborate manuals. We see the company changing addresses several times in 1982 and finally abandoning “Crystalware” altogether and publishing the last few games under the name “U.F.O. Software.” As we’ll soon see, John Bell also seems to have (at least for a time) changed his own name.

|

| Towards the end of its life, Crystalware briefly became U.F.O. Software. |

John Bell is an enigmatic figure (although not as enigmatic as Patty, about whom I’ve been able to find nothing). He claims to have worked for Lockheed in 1966, which is hard to reconcile with the best candidate I can find, who was born in 1948. Even that candidate has used both “A” and “F” as his middle initial. Crystalware used several addresses in Morgan Hill and San Martin (both south along the 101 from San Jose) during its existence. I think the Bells first owned a computer store, Crystal Computers, in Sunnyvale or Gilroy, before they decided to get into software development and publishing.

I corresponded earlier this month with Henry Ruddle, a programmer who did most of the TRS-80 adaptations of the game. I had hoped he would confirm my suspicions that Bell was something of a lunatic, but the best he would offer is that he was “charismatic, loud, and very eccentric.”

John was very creative and could not stop thinking . . . or talking. [He] would tell wild stories about getting high on amphetamines or cocaine and staying up for three days cleaning his bathroom with a toothbrush . . . He often talked about his wild ambitions [like] a plan to create a virtual reality booth with 360 degree views projected on the walls using “laser cameras.”

Of Patty, Ruddle remembers that she was polite and very quiet, heavily into New Age philosophy and astrology.

There’s a long period of silence after the collapse of the company, but in the late 1990s, Bell, now using the name “J. B. Michaels,” started promising an upcoming game called Clonus 2049 A.D. It never materialized, but you can read about it–sort-of–on the Crystalware Defense and Nanotechnology Facebook page, where an “actress from Hollywood” has recorded the incomprehensible opening text. Yes, John Bell is still using the Crystalware name. His various LinkedIn profiles give him as the CEO of Crystalware, CrystalwareVR, Crystalware Defense and Nanotechnology, or just “CDN.” The address is listed in Charleston, West Virginia. On the various pages associated with Bell and these companies, we learn that James Cameron’s The Terminator was plagiarized from the original Clonus, that Bell had a heart attack in 2018, and that he’s working on a virtual reality game called World of Twine.

I haven’t rated any of Crystalware’s games very high, and I was actively angry by the time I got to Quest for Power, but in retrospect I have to give the company credit for originality and a certain amount of sincerity. Most of Crystalware’s titles show no dependence on any previous game or series. Instead of generic high-fantasy settings, they went with unique, specific settings based on history or literature. Adding a “mystery” and cash prize to each title (even if I never really understood what they were going for) was an interesting touch, and letters to their newsletter (if authentic) suggest that they did pay. The thorough documentation that each game received, the manuals full of backstories and lore and quotes, the newsletter with so many promises, all suggest that the company was mostly unaware that it was a sausage factory. This was in the “dark age,” after all. Wizardry and Ultima were released in 1981 but hadn’t really made an impact yet. From the testimonies above, it’s easy to see John Bell as an Ed Woodish character, willing to wrap and print anything, in love with the process of creation that eclipsed his own abilities as a creator. But I suppose there are days when I’ll take that over auteurs so obsessed with quality that you end up waiting a decade between titles. Every genre needs its pulp.

I haven’t rated any of Crystalware’s games very high, and I was actively angry by the time I got to Quest for Power, but in retrospect I have to give the company credit for originality and a certain amount of sincerity. Most of Crystalware’s titles show no dependence on any previous game or series. Instead of generic high-fantasy settings, they went with unique, specific settings based on history or literature. Adding a “mystery” and cash prize to each title (even if I never really understood what they were going for) was an interesting touch, and letters to their newsletter (if authentic) suggest that they did pay. The thorough documentation that each game received, the manuals full of backstories and lore and quotes, the newsletter with so many promises, all suggest that the company was mostly unaware that it was a sausage factory. This was in the “dark age,” after all. Wizardry and Ultima were released in 1981 but hadn’t really made an impact yet. From the testimonies above, it’s easy to see John Bell as an Ed Woodish character, willing to wrap and print anything, in love with the process of creation that eclipsed his own abilities as a creator. But I suppose there are days when I’ll take that over auteurs so obsessed with quality that you end up waiting a decade between titles. Every genre needs its pulp.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/04/closing-books-on-crystalware.html