From The CRPG Addict

Abandoned Places: A Time for Heroes

Hungary

ArtGame (developer); Electronic Zoo (publisher)

Released 1992 for Amiga and DOS

Date Started: 15 May 2020

Date Ended: 4 June 2020

Total Hours: 33

Difficulty: Moderate (3/5) but very imbalanced

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

Summary:

The first game from a Hungarian developer, Abandoned Places offers typical Dungeon Master-style exploration, combat, and mechanical puzzle solving in a series of tiled 22 x 22 dungeons and dungeon levels. These locations are tied loosely together by a top-down overworld in which characters can visit a variety of menu towns and similar locations. The mostly-irrelevant story has four resurrected heroes from ancient times trying to stop the return of an ancient evil named Bronakh. The full game requires the party to defeat 27 dungeon levels, but different players will encounter different levels early in the game depending on where they pick up the main quest thread.

*****

Bronakh’s volcanic lair ended up being nine more levels, pitched in difficulty somewhere between the earlier, easy dungeons and the difficult Halls of Rage. Honestly, I wouldn’t have minded if the game had just consisted of the Halls of Rage and Bronakh’s fortress, maybe with a menu town on top. It would have been a tighter, more challenging game without a lot of wasted time before the main event.

As I mentioned in my penultimate entry, Bronakh whisked us directly from the Halls of Rage to his fortress without giving us a chance to level up. It turned out that I could just turn around, go up the stairs, and exit the volcano. In fact, the general theme of Bronakh’s nine-level lair was to require full exploration of each level, but ultimately in service of finding a key that unlocked a down staircase rather close to the up staircase. Thus, even deep in the fortress, a return to town was possible with minimal effort.

Bronakh’s levels were more challenging than the rest of the game, but I still wouldn’t say they were as challenging as Dungeon Master or even Eye of the Beholder. They were perhaps deadlier, in that fireballs and lightning bolts came flinging at my party it seems like every third step. I eventually got to the point where I just shrugged off the fact that my characters seemed to be taking constant damage for no visible reason. I reloaded a lot and took advantage of safe spaces to rest multiple times. My cleric got a resurrection spell eventually, and between that and “Heal,” I could deal with most problems as long as he kept his spell points up.

|

| Wandering into the wrong room in Bronakh’s lair. |

As I explored, I tried to make a full accounting of the different mechanical devices that the game uses. They include:

- Wall switches, some activated by hands, some by keys, that open walls and doors in other parts of the dungeon.

- Floor plates that open walls and doors in other parts of the dungeon.

- Illusory walls. Generally, you can just walk through them but “Detect Illusion” lets you see through them entirely.

|

| This was a rare illusory door that looked like a regular wall until I cast the spell. |

- Doors that require finding keys.

- Doors that have switches.

- Multiple doors whose switches open each other rather than the doors they’re attached to.

- Traps that cause fireballs or lightning bolts to hit you from the nearest wall.

- Fireballs and lightning bolts that fly out of the walls and corridors around you in absence of any trigger. Sometimes you can block these with plants, statues, or temporary walls created with the “Create Wall” spell.

- Teleportation squares, including those that teleport you in a sequence around a particular part of the dungeon, so it’s like you’re on a never-ending conveyor belt.

- Anti-magic squares.

- Spinners, some of which spin continually, some of which turn you once or twice. It got to the point that every major intersection in Bronakh’s had one of these.

- Water squares, for which you must cast “Swimming” to keep from taking damage.

- Squares perpetually on fire, for which you must cast “Walk on Fire” to keep from taking damage.

|

| Here we have water and fire in a row. |

- Cobwebs, which must be destroyed with the “Fire Path” spell, which turns them into fire squares.

- Potted plants (some of them hostile) and statues that you have to push and pull to clear paths or reveal hidden keys.

- Pits that lead to small lower areas of the same level. You can use ropes to lower yourself without damage and “Climb” to get back up, or “Levitate” to avoid them entirely.

Notably absent from this list are pressure plates, and the types of puzzles that require you to weigh down those plates, either with characters or monsters. You also can’t throw items into teleporters–just yourself–which limits some of the fun puzzles other games in this subgenre have allowed.

Through most of the game, the wall/door/switch ratio was 1:1 and one-directional, so that every time you found a switch, you could confidently activate it, knowing that it would open a door or wall that you needed open. Bronakh’s got a little more fiendish by having some of its switches close areas that you needed open. It took me a while to learn to stop activating switches and instead to treat the game more like Dungeon Master where you explore first and slowly, carefully work on your switches later.

Both the Halls of Rage and Bronakh’s did a good job of stringing these multiple options together. For instance, one of the levels has a series of pits that you needed to cross with “Levitate,” only to put an anti-magic square on the pit in the middle. This caused “Levitate” to snuff out and drop me through to a waiting fire square below. I had to “Jump” to avoid this particular square..

|

| Usually the game makes you fail once to figure it out, but this time it gave me a hint. |

I don’t love this kind of gameplay but I can appreciate it, and thus my only major complaint is that a couple of levels had keys allocated in such a way that you could put yourself in a “walking dead” situation if you didn’t open doors in a particular order. There’s never any excuse for that.

Enemies weren’t pushovers, but the continued to be the least important part of navigating the dungeon levels, at least until Level 8, where several of the enemies were capable of frequent, high-damage fireballs. It turns out that the creators anticipated the experience imbalance between fighters and spellcasters and thus set the level requirements much lower for the latter. Everyone reached the end of the game at their maximum levels, which was 8. Inventory rewards mostly stopped after the Halls of Rage, and I found I didn’t need any money after that. I only needed to retreat to town to get my last levels.

|

| These dino-looking things were pretty tough. |

The ninth and last level was large and mostly open, though with a few corridors and pillars to use for hiding and regrouping. Bronakh was the only enemy–a robed figure without much menace or character. He hit hard with spells, though, and took a long time to kill–so long that when I finally managed to kill him but had two of my own characters dead, I declined to reload and just moved forward through the final door.

|

| Casting a “Toxic Cloud” at Bronakh while he hammers me with something or other. |

The endgame cinematic showed the same sage who had resurrected the heroes sitting at his desk.

And so with the fall of Bronakh, the Kalynthian Empire is ready for a new age of peace and harmony: the age of union–when the lands of the world will at last be rejoined. For you it will be a time to build a new life, to meet new friends and remember old ones lost. And to watch and wait for the evil that can never sleep and must never be forgotten. The time of heroes will come again.

As the final words disappear, the door behind the sage opens to reveal a skeletal figure with glowing eyes just before we return to the main menu.

|

| We never did find out who this guy was. |

In the GIMLET, the game earns:

- 3 points for the game world. I found the framing narrative derivative and poorly reflected in the game itself. The map was mostly wasted.

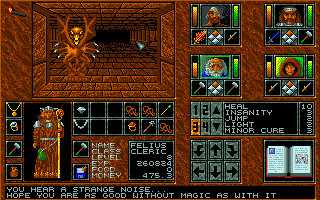

- 3 points for character creation and development. There’s no “creation” as such–just a selection from a gallery of heroes. Development is moderately satisfying, particularly in the acquisition of new spells, but forcing every player to have two warriors, a cleric, and a mage just reduces replayability.

- 1 point for a minor amount of NPC interaction to guide the quest.

- 5 points for encounters and foes. The game’s enemies are maddeningly unnamed, and while they do have some special attacks and defenses that you might want to plan tactics around, each enemy type lasts for such a brief time that it’s hardly worth analyzing them. I use this category for the quality of puzzles, which we’ve mostly already covered

- 5 points for magic and combat. I like that the spells were integrated with puzzle-solving. While the game makes good use of the “cool down” system of Dungeon Master, it lacks some of the timing and punch of other games of its ilk, and for most of the game it was too easy.

|

| Fighting some kind of goofy flying thing. |

- 4 points for equipment. You get the basics: two hand slots, armor, a ring, and a necklace or amulet. There weren’t many upgrades, especially towards the end. There’s no way to see weapon statistics, but at least the ability to sell weapons imparts some estimate of relative worth.

- 2 points for the economy. The game has one, but it’s not very well done. I sold a lot but hardly bought anything.

- 3 points for quests. It has a main quest, of course, and there are a couple of different paths through the early dungeons, although which you take is more a matter of luck than “choice.”

- 3 points for graphics, sound, and interface. It gets 1 for each. I thought the graphics and sound effects were only okay, and for everything I liked about the interface (e.g., the use of function keys to execute attacks), there was something I didn’t like (e.g., having to scroll slowly through the spell list). The automap, which you don’t acquire until the third dungeon, stopped working in all of the later dungeons.

- 3 points for gameplay. I have to give it a small amount of credit for some nonlinearity and some replayability, but the difficulty was too imbalanced and the pacing was horrible.

That gives us a subtotal of 32, from which I subtract 1 for bugs, for a final score of 31. The “invulnerability” bug dogged me throughout the final dungeon. It seemed like whenever the processor got overwhelmed by too much happening on the screen–too many spells or flying lightning bolts or whatever–enemies just froze in place. They stopped attacking, but they were also impossible to kill and were blocking the corridors. On the positive side, I never encountered any of the bugs some other players report, such as an inability to ever find some of the dungeons.

It doesn’t appear that the game ever had a North American release, and thus all the reviews are from European magazines, particularly Amiga magazines. I rubbed my hands and got ready to excoriate British Amiga reviewers for getting everything wrong, but they mostly gave the game a fair shake. Amiga Power said in February 1992 that: “[It] may not represent the new standard in RPGs–it’s a bit too scrappy in certain areas for that–but you can bet your bottom dollar it’ll be responsible for a great many hours of lost sleep among the die-hard D&D fraternity.” Overall, the magazine gave it an 80. Reviews from CU Amiga in March 1992 (83), Amiga Action in March 1992 (82), and Amiga Format in February 1992 (80), all basically said the same things: the graphics are a bit rough and the game is a bit too easy, but otherwise it wasn’t a bad experience. None of them seem to have made it all the way to the Halls of Rage before their reviews, however, which I imagine would have changed things. Continental reviews were less charitable, mostly in the 60s and 70s. The worst came from the German PC Player (37), but they didn’t get to it until August 1993, at which point they were comparing it to Ultima Underworld and Betrayal at Krondor.

Some of the reviews mention bits of marketing from Electronic Zoo that said the game had “over 100” levels. Even accounting for the extra early-game dungeons that you don’t experience if you take different paths, the only way that is true is if you count the little interconnected sections of dungeon levels and not the entirety of the levels. It’s a disingenuous bit of marketing. Electronic Zoo also advertised that it would take more than two months to finish. It took me three weeks, but I don’t really see how it makes sense to measure playing time in months anyway.

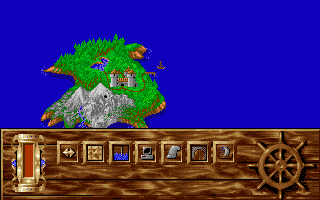

Abandoned Places was one of three games from Hungarian developer ArtGame. Abandoned Places 2 came along in 1993 and Piracy on the High Seas was published in 1992; it features an overworld interface very similar to Abandoned Places. Screenshots from the sequel show improved monster graphics, a redesigned interface, and first-person exploration of the overworld.

|

| Travel in Piracy uses an interface nearly identical to Places. |

If I can trust a few sites, the principals of ArtGame–including Ferenc Staengler, István Fábián, Sandor Hadas, and György Dragon–were university students when they met and decided to make games. An initial version of the game failed to find a publisher, although Electronic Arts expressed interest if the team came up with better graphics. They spent several months on a graphical overhaul, but by the time they resubmitted, EA had already agreed to publish Raven Software’s Black Crypt and didn’t want two games in the same subgenre at the same time. They ultimately struck a deal with United Kingdom-based publisher Electronic Zoo.

On a page in which Abandoned Places 2 is offered for free, Staengler recounts how he and his colleagues were treated by International Computer Entertainment, which bought the ailing Electronic Zoo and published the sequel. I’m not sure how much of this story (e.g., receiving no royalties) has anything to do with the original game and original publisher, so I’ll leave off any more history until next year, when I cover the sequel and hopefully have managed to make contact with Staengler or one of the other developers. It is worth noting that even in the first game’s manual, the publisher apparently made the developers anglicize their names: Ferenc Staengler became “Francis” Staengler, István Fábián became “Steve Fabian,” and György Dragon was rendered as “George Dragon.”

I found Abandoned Places underwhelming for most of its run, particularly in comparison to the better games of its sub-genre, but I do like that it tried to integrate Dungeon Master with an overworld, towns, an economy, and other features from outside the typical Dungeon Master line. There’s no reason that a good dungeon crawl has to be 15 levels straight down; you can enjoy the same mechanics while still pausing for story elements and while allowing the characters to spend a night in a tavern. Abandoned Places didn’t do it particularly well, but I’m glad that it tried to do it at all. I look forward to seeing if the sequel improves.

We’ll head back to The Legacy next, of course, but whether the next game after that is a return to Ultima VII or a look at Mythos 1 depends on how far I get retracing my steps in the former.

***********

Trying something. Let’s assume I have a Famicom Disk System (FDS) file and an IPS patch for it. How do I put them together? I can find all kinds of instructions for doing it with an SNES file, but not for an FDS file.

***********

Trying something. Let’s assume I have a Famicom Disk System (FDS) file and an IPS patch for it. How do I put them together? I can find all kinds of instructions for doing it with an SNES file, but not for an FDS file.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/06/abandoned-places-won-with-summary-and.html