The full extent of Wolfenstein 3D‘s popularity during 1992 and 1993 is difficult to quantify with any precision due to the peculiarities of the shareware distribution model. But the one thing we can say for sure is that it was enormously popular by any standard. Apogee sold roughly 200,000 copies of the paid episodes, yet that number hardly begins to express the game’s real reach. Most people who acquired the free episode were content with it alone, or couldn’t afford to buy the other installments, or had friends who had bought them already and were happy to share. It thus seems reasonable to assume that the total number of Wolfenstein 3D players reached well into seven digits, putting the game’s exposure on a par with The 7th Guest, the boxed industry’s biggest hit of 1993, the game generally agreed to have put CD-ROM on the map. And yet Wolfenstein 3D‘s impact would prove even more earthshaking than that of The 7th Guest in the long run.

One telling sign of its influence — and of the way that it was just a fundamentally different type of game than The 7th Guest, that stately multimedia showpiece — is the modding scene that sprang up around it. The game’s levels were stored in a rather easily decipherable format: the “WAD” file, standing for “Where’s All the Data?” Enterprising hackers were soon writing and distributing their own level editors, along with custom levels. (The most popular of them all filled the corridors of the Nazi headquarters with facsimiles of the sickly sweet, thuddingly unclever, unbelievably grating children’s-television character Barney the Dinosaur and let you take out your frustrations with an automatic weapon.) The id boys debated fiercely among themselves whether they should crack down on the modders, but John Carmack, who had read Steven Levy’s landmark book Hackers at an impressionable age and thoroughly absorbed its heroes’ ethos of openness and transparency, insisted that people be allowed to do whatever they wished with his creation. And when Carmack put his foot down, he always got his way; at the end of the day, he was the one irreplaceable member of the id collective, and every one of the others knew it.

With Wolfenstein 3D‘s popularity soaring, the id boys started eyeing the territory of the boxed publishers greedily. They struck a deal with a company called FormGen to release a seventh, lengthier installment of the game exclusively as a boxed retail product; it appeared under the name of Spear of Destiny in September of 1992. Thus readers of magazines like Computer Gaming World could scratch their heads that fall over two separate luridly violent full-page advertisements for Wolfenstein 3D games, each with a different publisher’s name at the bottom. Spear of Destiny sold at least 100,000 copies at retail, both to hardcore Wolfenstein 3D addicts who couldn’t get enough and to many others, isolated from the typical means of shareware distribution, who came upon the game for the first time in this form.

Even Nintendo came calling with hat in hand, just a couple of years after summarily rejecting id’s offer to make a version of Super Mario Bros. 3 that ran on computers. The id boys now heeded Nintendo’s plea to port Wolfenstein 3D to the new Super Nintendo Entertainment System, whilst also grudgingly agreeing to abide by the dictates of Nintendo’s infamously strict censors. They had no idea what they had signed up for. Before they were through, Nintendo demanded that they replace blood with sweat, guard dogs with mutant rats, and Adolf Hitler, the game’s inevitable final boss, with a generic villain named the “Staatmeister.” They hated this bowdlerization with a passion, but, having agreed to do the port, they duly saw it through, muttering “Never again!” to themselves all the while. And indeed, when they were finished they took a mutual vow never to work with Nintendo again. Who needed them? The world was id’s oyster.

By now, 1992 was drawing to a close, and they all felt it was high time that they moved on to the next new thing. For everyone at id, and most especially John Carmack, was beginning to look upon Wolfenstein 3D with a decidedly jaundiced eye.

The dirty little secret that was occluded by Wolfenstein 3D‘s immense success was that it wasn’t all that great a game once it was stripped of its novelty value. Its engine was just too basic to allow for compelling level design. You glided through its corridors as if you were on a branching tram line that had been mashed together with a fairground shooting gallery, trying to shoot the Nazis who popped up before they could shoot you. The lack of any sort of in-game map meant that you didn’t even know where you were most of the time; you just kept moving around shooting Nazis until you stumbled upon the elevator to the next level. Anyone who made it through seven episodes of this — and make no mistake, there were plenty of players who did — either had an awful lot of aggression to vent or really, really loved the unprecedented look and style of the game. The levels were even boring for their designers. John Romero:

Tom [Hall] and I [designed] levels [for Wolfenstein 3D] fast. Making those levels was the most boring shit ever because they were so simple. Tom was so bored; I kept on bugging him to do it. I told him about Scott Miller’s 300ZX and George Broussard’s Acura NSX. We needed cool cars too! Whenever he got distracted, I’d tell him, “Dude, NSX! NSX!”

Tom Hall had it doubly hard. The fact was, the ultra-violence of Wolfenstein 3D just wasn’t really his thing. He preferred worlds of candy-apple red, not bloody scarlet; of precocious kids and cuddly robots, not rabid vigilantes and sadistic Nazis. Still, he was nothing if not a team player. John Romero and Adrian Carmack had gone along with him for Commander Keen, so it was only fair that he humored them with Wolfenstein 3D. But now, he thought, all of that business was finally over, and they could all start thinking about making a third Commander Keen trilogy.

Poor Tom. It took a sweetly naïve nature like his to believe that the other id boys would be willing to go back to the innocent fun of their Nintendo pastiches. Wolfenstein 3D was a different beast entirely than Commander Keen. It wasn’t remarkable just for being as good as something someone else had already done; it was like nothing anyone had ever done before. And they owned this new thing, had it all to themselves. Hall’s third Commander Keen trilogy just wasn’t in the cards — not even when he offered to do it in 3D, using an updated version of the Wolfenstein 3D engine. Cute and whimsical was id’s yesterday; gritty and bloody was their today and, if they had anything to say about it, their tomorrow as well.

Digging into their less-than-bulging bag of pop-culture reference points, the id boys pulled out the Alien film franchise. What a 3D game those movies would make! Running through a labyrinth of claustrophobic corridors, shooting aliens… that would be amazing! On further reflection, though, no one wanted the hassle that would come with trying to live up to an official license, even assuming such a thing was possible; id was still an underground insurgency at heart, bereft of lawyers and Hollywood contacts. Their thinking moved toward creating a similar effect via a different story line.

The id boys had a long-running tabletop Dungeon & Dragons campaign involving demons who spilled over from their infernal plane of existence into the so-called “Prime Material Plane” of everyday fantasy. What if they did something like that, only in a science-fiction context? Demons in space! It would be perfect! It was actually John Carmack, normally the id boy least engaged by these sorts of discussions, who proposed the name. In a scene from the 1986 Martin Scorsese movie The Color of Money, a young pool sharp played by Tom Cruise struts into a bar carrying what looks like a clarinet case. “What you got in there?” asks his eventual patsy with an intimidating scowl. As our hero opens the case to reveal his pool cue, he flashes a 100-kilowatt Tom Cruise smile and says a single word: “Doom.”

Once again, Tom Hall tried to be supportive and make the best of it. He still held the official role of world-builder for id’s fictions. So, he went to work for some weeks, emerging at last with the most comprehensive design document which anyone at id had ever written, appropriately entitled The DOOM Bible. It offered plenty of opportunity for gunplay, but it also told an earnest story, in which you, as an astronaut trapped aboard a space station under assault by mysterious aliens, gradually learned to your horror that they were literal demons out of Hell, escaping into our dimension through a rift in the fabric of space-time. It was full of goals to advance and problems to solve beyond that of mowing down hordes of monsters, with a plot that evolved as you played. The history of gaming would have been markedly different, at least in the short term, if the other id boys had been interested in pursuing Hall’s path of complex storytelling within a richly simulated embodied virtual reality.

As it was, though, Hall’s ambitions landed with a resounding thud. Granted, there were all sorts of valid practical reasons for his friends to be skeptical. It was true enough that to go from the pseudo-3D engine of Wolfenstein 3D to one capable of supporting the type of complex puzzles and situations envisioned by Hall, and to get it all to run at an acceptable speed on everyday hardware, might be an insurmountable challenge even for a wizard like John Carmack. And yet the fact remains that the problem was at least as much one of motivation as one of technology. The other id boys just didn’t care about the sort of things that had Tom Hall so juiced. It again came down to John Carmack, normally the least articulate member of the group, to articulate their objections. “Story in a game,” he said, “is like story in a porn movie. It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.”

Tom Hall held out for several more months, but he just couldn’t convince himself to get fully onboard with the game his friends wanted to make. His relationship with the others went from bad to worse, until finally, in August of 1993, the others asked him to leave: “Obviously this isn’t working out.” By that time, DOOM was easily the most hotly anticipated game in the world, and nobody cared that it wouldn’t have a complicated story. “DOOM means two things,” said John Carmack. “Demons and shotguns!” And most of its fans wouldn’t have it any other way, then or now.

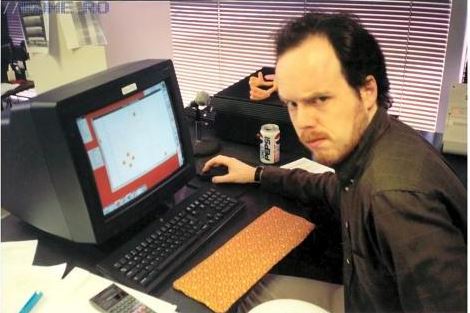

Tom Hall doesn’t look very happy about working on DOOM. Note the computer he works with: a NeXT workstation rather than an MS-DOS machine. John Carmack switched virtually all development to these $10,000 machines in the wake of Wolfenstein 3D‘s success, despite their tiny market footprint. The fact that the DOOM code was thus designed to be cross-platform from the beginning was undoubtedly a factor in the plethora of ports that appeared during and after its commercial heyday — that in fact still continue to appear today any time a new platform reaches a critical mass.

Making DOOM wound up requiring more than three times as many man-hours as anything the id boys had ever done before. It absorbed their every waking hour from January of 1993 to December of that year. Early on in that period, they decided that they wouldn’t be publishing it through Apogee. Cracks in the relationship between the id boys and Scott Miller had started forming around the latter’s business practices, which were scrupulously honest but also chaotic in that way dismayingly typical of a fast-growing business helmed by a first-time entrepreneur. Reports kept reaching id of people who wanted to buy Wolfenstein 3D, but couldn’t get through on the phone, or who managed to give Apogee their order only to have it never fulfilled.

But those complaints were perhaps just a convenient excuse. The reality was that the id boys just didn’t feel that they needed Apogee anymore. They had huge name recognition of their own now and plenty of money coming in to spend on advertising and promotion, and they could upload their new game to the major online services just as easily as Scott Miller could. Why keep giving him half of their money? Miller, for his part, handled the loss of his cash cow with graceful aplomb. He saw it as just business, nothing personal. “I would have done the same thing in their shoes,” he would frequently say in later interviews. He even hired Tom Hall to work at Apogee after the id boys cast him adrift in the foreign environs of Dallas.

Jay Wilbur now stepped into Miller’s old role for id. He prowled the commercial online services, the major bulletin-board systems, and the early Internet for hours each day, stoking the the flames of anticipation here, answering questions there.

And there were lots of questions, for DOOM was actually about a bit more than demons and shotguns: it was also about technology. Whatever else it might become, DOOM was to be a showcase for the latest engine from John Carmack, a young man who was swiftly making a name for himself as the best game programmer in the world. With DOOM, he allowed himself to set the floor considerably higher in terms of system requirements than he had for Wolfenstein 3D.

System requirements have always been a moving target for any game developer. Push too hard, and you may end up releasing a game that almost no one can play; stay too conservative, and you may release something that looks like yesterday’s news. Striking precisely the right point on this continuum requires knowing your customers. The Apogee shareware demographic didn’t typically have cutting-edge computers; they tended to be younger and a bit less affluent than those buying the big boxed games. Thus id had made it possible to run Wolfenstein 3D on a two-generations-behind 80286-based machine with just 640 K of memory. The marked limitations of its pseudo-3D engine sprang as much from the limitations of such hardware as it did from John Carmack’s philosophy that, any time it came down to a contest between fidelity to the real world and speed, the latter should win.

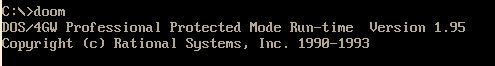

He still held to that philosophy as firmly as ever when he moved on to DOOM, but the slow progression of the market’s trailing edge did give him more to work with: he designed DOOM for at least an 80386-based computer — 80486 recommended — with at least 4 MB of memory. He was able to mostly ignore that bane of a generation of programmers, MS-DOS’s inability to seamlessly address memory beyond 640 K, by using a relatively new piece of software technology called a “DOS extender,” inspired to a large extent by Microsoft’s recent innovations for their MS-DOS-hosted versions of Windows. By transparently shifting the processor between its real and protected modes on the fly, Rational Systems’s “DOS/4GW” could make it seem to the programmer as if all of the machine’s memory was as effortlessly available as the first 640 K. DOS/4GW was included in the latest versions of what had heretofore been something of an also-ran in the compiler sweepstakes: the C compiler made by a small Canadian company known as Watcom. Carmack chose the Watcom compiler because of DOS/4GW; DOOM would quite literally have been impossible without it. In the aftermath of DOOM‘s prominent use of it, Watcom’s would become the C compiler of choice for game development, right through the remaining years of the MS-DOS-gaming era.

Rational Systems, the makers of DOS/4GW, were clever enough to stipulate in their licensing terms that the blurb above must appear whenever a program using it is started. Thus DOOM served as a prominent advertisement for the new software technology as it exploded across the world of computing in 1994. Soon you would have to look far and wide to find a game that didn’t mention DOS/4GW at startup.

Thanks not only to these new affordances but also — most of all, really — to John Carmack’s continuing evolution as a programmer, the DOOM engine advanced beyond that of Wolfenstein 3D in several important ways. Ironically, his work on the detested censored version of Wolfenstein 3D for the Super NES, a platform designed with 2D sprite-based games in mind rather than 3D graphics, had led him to discover a lightning-fast new way of sorting through visible surfaces, known as binary space partitioning, in a doctoral thesis by one Bruce Naylor. It had a well-nigh revelatory effect on the new engine’s capabilities.

That said, the new engine did remain caught, like its predecessor, in a liminal space between 2D and true 3D; it was just that it moved significantly further on the continuum toward the latter. No longer must everything and everyone exist on the same flat horizontal plane; you could now climb stairs and jump onto desks and daises. And walls must no longer all be at right angles to one another, meaning the world needed no longer resemble one of those steel-ball mazes children used to play with.

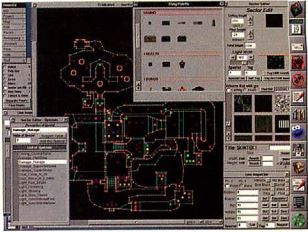

The DOOM level editor was a much more complicated tool than its Wolfenstein 3D equivalent, reflecting the enhanced capabilities of John Carmack’s latest engine. Most notably, the designer now had at his disposal the third dimension of height.

On the other hand, walls must still all be exactly vertical, and floors and ceilings must all be exactly horizontal; DOOM allowed stairs but not hills or ramps. These restrictions made it possible to map textures onto the environment without the ugly discontinuities that had plagued Blue Sky Productions’s earlier but more “honest” 3D game Ultima Underworld. Texture mapping in DOOM, while by no means perfectly perspective-correct, was at least closer to that ideal than in the older game. DOOM makes such a useful study in game engineering because it so vividly illustrates that faking it convincingly for the sake of the player is better than simulating things which delight only the programmer of the virtual world. Its engine is perfect for the game it wants to be.

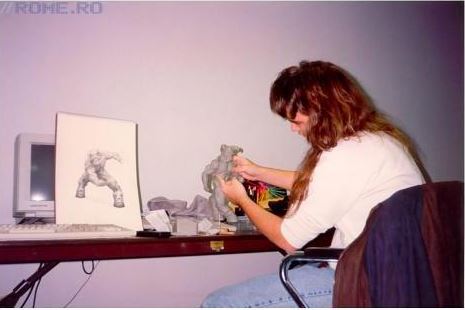

In a telling sign of John Carmack’s march toward a more complete 3D engine, the monsters in DOOM were sculpted as three-dimensional physical models by Adrian Carmack and Greg Punchatz, an artist hired just for the task. (The former is shown above.) The id boys then took snapshots of the models from eight separate angles for insertion into the game.

The value of the simple addition of height to the equation was revealed subtly — admittedly not an adverb often associated with DOOM! — as soon as you started the game. Instead of gliding smoothly about like a tram, your view now bobbed with uncanny verisimilitude as you ran about. You might never consciously notice the effect, but it made a huge difference to your feeling of really being in the world; if you tried to go back to Wolfenstein 3D after playing DOOM, you immediately had the feeling that something was somehow off.

But the introduction of varying height was most important for what it meant in terms of the game’s tactical possibilities. Now monsters could stand on balconies and shoot fireballs down at you, or you could do the same to them. Instead of a straightforward shooting gallery, the world of DOOM became a devious place of traps and ambushes. A clever hack allowed for portals such as windows, adding another level of tactical depth. (Walls with windows were actually implemented as free-standing objects in the engine rather than “real” walls; the same technique allowed for many other types of partial barriers.) Carmack’s latest engine also supported variable levels of lighting for the first time, which opened up a whole new realm of both dramatic and tactical possibility in itself; entering an unexplored pitch-dark room could be, to say the least, an intimidating prospect.

This outdoor scene nicely showcases some of the engine’s capabilities. Note the fireball flying toward you. It’s implemented as a physical object in the world like any other.

In addition, the new engine dramatically improved upon the nearly non-existent degree of physics simulation in Wolfenstein 3D. Weight and momentum were implemented; even bullets were simulated as physical objects in the world. A stereo soundscape was implemented as well; in addition to being unnerving as all get-out, it could become another vital tactical tool. Meanwhile the artificial intelligence of the monsters, while still fairly rudimentary, advanced significantly over that of Wolfenstein 3D. It was even possible to lure two monsters into fighting each other instead of you.

John Carmack also added a modicum of support for doing things other than killing monsters, although to nowhere near the degree once envisioned by Tom Hall. The engine could be used to present simple forms of set-piece puzzles, such as locked doors and keys, switches and levers for manipulating parts of the environment: platforms could move up and down, bridges could extend and retract. And in recognition of this added level of complexity, which could suddenly make the details of the geography and your precise position within it truly relevant, the engine offered a well-done auto-map for keeping track of those things.

Of course, none of these new affordances would matter without level designs that took advantage of them. The original plan was for Tom Hall and John Romero to create the levels. But, as we’ve seen, Hall just couldn’t seem to hit the mark that the id boys were aiming for. After finally dismissing him, they realized that Romero still needed helped to shoulder the design burden. It arrived from a most unlikely source — from a fellow far removed from the rest of the id boys in age, experience, and temperament.

Sandy Petersen was already a cult hero in certain circles for having created a tabletop RPG called Call of Cthulhu in 1981. Based on the works of the horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, it was the first RPG ever to convincingly transcend the kill-monsters-to-level-up-so-you-can-kill-bigger-monsters dynamic of Dungeons & Dragons. But Call of Cthulhu remained a cult game even when the tabletop-RPG boom was at its height, and by the early 1990s Petersen was serving as an in-house design consultant at the computer-game publisher MicroProse. Unhappy in this role, he sent his résumé to the upstart id.

The résumé was greeted with considerable skepticism. It’s doubtful whether any of the id boys fully grasped the significance of Petersen’s achievement with Call of Cthulhu; while they were hardcore tabletop-RPG players, they were perfectly happy with the traditional power-gaming approach of Dungeons & Dragons, thank you very much. Still, the résumé was more impressive than any other they had received, and they did urgently need a level designer… they called him in for an interview.

Their initial skepticism wasn’t lessened by the man himself. Petersen was pudgy and balding, looking even older than his already ancient 38 years, coming across rather like a genial university professor. And he was a devout Mormon to boot, washed up among this tribe of atheists and nihilists. Surely it could never work out.

Nevertheless, they decided to grant him the favor of a test before they rejected him; he had, after all, flown all the way from Baltimore to Dallas just to meet with them. They gave him a brief introduction to the DOOM engine and its level editor, and asked him to throw something together for them. Within minutes, Petersen produced a cunningly dramatic trap room, featuring lights that suddenly winked out when the player entered and a demon waiting in ambush behind a hidden door. He was hired.

Romero and Petersen proved to complement each other very well, with individual design aesthetics that reflected their personalities. Romero favored straight-up carnage — the more demon blood the better — while Petersen evinced a subtler, more cerebral approach in levels that could almost have a puzzle-like feel, where charging in with shotgun blazing was usually not the best tactic. Together the two approaches gave the game a nice balance.

Indeed, superb level design became DOOM‘s secret weapon, one that has allowed it to remain relevant to this day, when its degree of gore and violence seems humdrum, its pixels look as big as houses, and the limitations of its engine seem downright absurd. (You can’t even look up or down, for Pete’s sake. Nor is there a “jump” command, meaning that your brawny superman can be stopped in his tracks by an inconveniently high curb.)

It’s disarmingly easy to underestimate DOOM today on your first encounter with it, simply because its visual aesthetic seems so tossed-off, so hopelessly juvenile; it’s the same crude mixture of action movies, heavy-metal album covers, and affected adolescent nihilism that defined the underground game-cracking scene of the 1980s. And yet behind it all is a game design that oozes as much thought and care as it does blood. These levels were obsessed over by their designers, and then, just as importantly, extensively critiqued by the other id boys and their immediate hangers-on, who weren’t inclined to pull their punches. Whatever your opinion of DOOM as a whole and/or the changes it wrought to the culture of gaming — I for one have thoroughly mixed feelings at best on both of those subjects — one cannot deny that it’s a veritable clinic of clever level design. In this sense, it still offers lessons for today’s game developers, whether they happen to be working inside or outside of the genre it came to define.

DOOM‘s other, not-so-secret weapon went by the name of “deathmatch.”

There had been significant experimentation with networked gaming on personal computers in the past: the legendary designer Dani Bunten Berry had spent the last half-decade making action-strategy games that were primarily or exclusively intended to be played by two humans connected via modem; Peter Molyneux’s “god game” Populous and its sequels had also allowed two players to compete on linked computers, as had a fair number of others. But computer-to-computer multiplayer-only games never sold very well, and most games that had networked multiplayer as an option seldom saw it used. Most people in those days didn’t even own modems; most computers were islands unto themselves.

By 1993, however, the isolationist mode of computing was slowly being nibbled away at. Not only was the World Wide Web on the verge of bursting into the cultural consciousness, but many offices and campuses were already networked internally, mostly using the systems of a company known as Novell. In fact, the id boys had just such a system in their Dallas office. When John Carmack told John Romero many months into the development of DOOM that multiplayer was feasible, the latter’s level of excitement was noteworthy even for him: “If we can get this done, this is going to be the fucking coolest game that the planet Earth has ever fucking seen in its entire history.” And it turned out that they could get it done because John Carmack was a programming genius.

While Carmack also implemented support for a modem connection or a direct computer-to-computer cable, it was under Novell’s IPX networking protocol that multiplayer DOOM really shined. Here you had a connection that was rock-solid and lightning-fast — and, best of all, here you could have up to four players in the same world instead of just two. You could tackle the single-player game as a team if you wanted to, but the id boys all agreed that deathmatch — all-out anarchy, where the last man standing won — was where the real fun lived. It made DOOM into more of a sport than a conventional computer game, something you could literally play forever. Soon the corridors at id were echoing with cries of “Suck it down!” as everyone engaged in frenzied online free-for-alls. Deathmatch was, in the diction of the id boys, “awesome.” It wasn’t just an improvement on what Wolfenstein 3D had done; it was something else from it that was genuinely new under the sun. “This is the shit!” chortled Romero, and for once it sounded like an understatement.

The excitement over DOOM had reached a fever pitch by the fall of 1993. Some people seemed on the verge of a complete emotional meltdown, and launched into overwrought tirades every time Jay Wilbur had to push the release date back a bit more; people wrote poetry about the big day soon to come (“The Night Before DOOM“), and rang id’s offices at all hours of the day and night like junkies begging for a fix.

Even fuddy-duddy old Computer Gaming World stopped by the id offices to write up a two-page preview. This time out, no reservations whatsoever about the violence were expressed, much less any of the full-fledged hang-wringing that had been seen earlier from editor Johnny Wilson. Far from giving in to the gaming establishment, the id boys were, slowly but surely, remaking it in their own image.

At last, id announced that the free first episode of DOOM would go up at the stroke of midnight on December 10, 1993, on, of all places, the file server belonging to the University of Wisconsin–Parkside. When the id boys tried to log on to do the upload, so many users were already online waiting for the file to appear that they couldn’t get in; they had to call the university’s system administrator and have him kick everyone else off. Then, once the file did appear, the server promptly crashed under the load of 10,000 people, all trying to get DOOM at once on a system that expected no more than 175 users at a time. The administrator rebooted it; it crashed again. They would have a hard go of things at the modest small-town university for quite some time to come.

Legend had it that when Don Woods first uploaded his and Will Crowthers’s game Adventure in 1977, all work in the field of data processing stopped for a week while everyone tried to solve it. Now, not quite seventeen years later, something similar happened in the case of DOOM, arguably the most culturally important computer game to appear since Adventure. The id boys had joked in an early press release that they expected DOOM to become “the number-one cause of decreased productivity in businesses around the world.” Even they were surprised by the extent to which that prediction came true.

Network administrators all over the world had to contend with this new phenomenon known as deathmatch. John Carmack had had no experience with network programming before DOOM, and in his naïveté had used a transmission method known as a broadcast package that forced every computer on the network, whether it was running DOOM or not, to stop and analyze every packet which every DOOM-playing computer generated. As reports of the chaos that resulted poured in, Carmack scrambled to code an update which would use machine-to-machine packets instead.

In the meantime, DOOM brought entire information-technology infrastructures to their knees. Intel banned the game; high-school and university computers labs hardly knew what had hit them. A sign posted at Carnegie-Mellon University before the day of release was even over was typical: “Since today’s release of DOOM, we have discovered [that the game is] bringing the campus network to a halt. Computing Services asks that all DOOM players please do not play DOOM in network mode. Use of DOOM in network mode causes serious degradation of performance for the players’ network, and during this time of finals network use is already at its peak. We may be forced to disconnect the PCs of those who are playing the game in network mode. Again, please do not play DOOM in network mode.” One clever system administrator at the University of Louisville created a program to search the hard drives of all machines on the network for the game, and delete it wherever it was found. All to no avail: DOOM was unstoppable.

But in these final months of the mostly-unconnected era of of personal computing — the World Wide Web would begin to hit big over the course of 1994 — a game still needed to reach those without modems or network cards in their computers in order to become a hit on the scale that id envisioned for DOOM. Jay Wilbur, displaying a wily marketing genius that went Scott Miller one better, decided that absolutely everyone should be allowed to distribute the first episode of DOOM on disk, charging whatever they could get for it: “We don’t care if you make money off this shareware demo. Move it! Move it in mass quantities.” For distribution, Wilbur realized, was the key to success. There are many ways to frame the story of DOOM, but certainly one of them is a story of guerrilla marketing at its finest.

The free episode of DOOM appeared in stores under many different imprints, but most, like this Australian edition, used the iconic cover id themselves provided. John Romero claims that he served as the artist’s model for the image.

The incentives for distribution were massive. If a little mom-and-pop operation in, say, far-off Australia could become the first to stick that episode onto disks, stick those disks in a box, and get the box onto store shelves, they could make a killing, free and clear. DOOM became omnipresent, inescapable all over the world. When you logged into CompuServe, there was DOOM; when you wandered into your local software store, there was DOOM again, possibly in several different forms of packaging; when you popped in the disk or CD that came with your favorite gaming magazine, there it was yet again. The traditional industry was utterly gobsmacked by this virulent upstart of a game.

As with Wolfenstein 3D, a large majority of the people who acquired the first episode of DOOM in one way or another were perfectly satisfied with its eight big levels and unlimited deathmatch play; plenty of others doubtless never bothered to read the fine print, never even realized that more DOOM was on offer if they called 1-800-IDGAMES with their credit card in hand. And then, of course, there was the ever-present specter of piracy; nothing whatsoever stopped buyers of the paid episodes from sharing them with all of their DOOM-loving friends. By some estimates, the conversion rate from the free to the paid episodes was as low as 1 percent. Nevertheless, it was enough to make the id boys very, very rich.

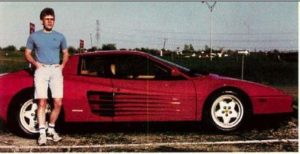

Sometimes $100,000 worth of orders would roll in on a single day. John Carmack and John Romero each went out and bought a new Ferrari Testarossa; now it was the turn of Scott Miller and George Broussard to look on the id boys’ cars with envy. Glossy magazines, newspapers, and television news programs all begged to visit the id offices, where they wondered over the cars in the parking lot and the unkempt young men inside screaming the most horrid scatological and sexual insults at one another as they played deathmatch. If nothing else, the id boys were certainly a colorful story.

The id boys’ cars got almost as much magazine coverage as their games. Here we see John Carmack with his Ferrari, which he had modified to produce 800 horsepower: “I want dangerous acceleration.”

Indeed, the id story is as close as gaming ever came to fulfilling one of its most longstanding dreams: that of game developers as rock stars, as first articulated by Trip Hawkins in 1983 upon his founding of Electronic Arts. Yet if Hawkins’s initial stable of developers, so carefully posed in black and white in EA’s iconic early advertisements, resembled an artsy post-punk band — the interactive version of Talking Heads — the id boys were meat-and-potatoes heavy metal for the masses — Metallica at their Black Album peak. John Romero, the id boy who most looked the part of rock star, particularly reveled in the odd sort of obsequious hero worship that marks certain corners of gamer culture. He almost visibly swelled with pride every time a group of his minions started chanting “We’re not worthy!” and literally bowed down in his presence, and wore his “DOOM: Wrote It!” tee-shirt until the print peeled off.

The impact DOOM was having on the industry had become undeniable by the time of the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1994. Here everyone seemed to want in on id’s action. The phrase “first-person shooter” had yet to be invented, so the many soon-to-be-released games of the type were commonly referred to as “DOOM clones” — or, as Computer Gaming World preferred, “DOOM toos.” The same magazine, still seeming just a trifle ambivalent about it all, called it the “3D action fad.” But this was no fad; these games were here to stay. The boxed publishers who had scoffed at the shareware scene a year or two before were now all scrambling to follow id’ lead. LucasArts previewed a DOOM clone set in the Star Wars universe; SSI, looking for a new lease on life after losing their coveted Dungeons & Dragons license, had multiple games of the type, including one using a rented version of id’s own technology.

And then, inevitably, there was id’s own DOOM II: Hell on Earth. As a piece of game design, it evinced no sign of the dreaded sophomore slump that afflicts so many rock groups — this even though it used the exact same engine as its predecessor, and even though John Romero, id’s rock-star-in-chief, was increasingly busy with extracurriculars and contributed only a handful of levels. His slack was largely taken up one American McGee, the latest scruffy rebel to join the id boys, a 21-year-old former auto mechanic who had suffered through an even more hardscrabble upbringing than the two Johns. After beginning at id as a tester, he had gradually revealed an uncanny talent for making levels that combined the intricacy of Sandy Petersen’s with the gung-ho flair of John Romero’s. Now, he joined Petersen and, more intermittently, Romero to create a game that was if anything even more devious than its predecessor. The id boys had grown cockier than ever, but they could still back it up.

John Romero in 1994, doing something the other id boys wished he would do a bit more of: making a level for DOOM II.

They were approached by a New York City wheeler-and-dealer named Ron Chaimowitz who wanted to publish DOOM II exclusively to retail. He had never had anything to do with computer games before; he had made his name in the music industry, where he had broken big acts like Gloria Estefan and Julio Iglesias, then moved on to publish Jane Fonda’s workout videos through his company GoodTimes Entertainment. But he had distribution connections — and, as Jay Wilbur has so recently proved, distribution often means everything. GoodTimes sold millions of videotapes through Wal-Mart, the exploding epicenter of heartland retail, and Chaimowitz promised that his new software label would be able to leverage those connections. He further promised to spend $2 million on advertising. He would prove as good as his word in both respects. Chaimowitz’s new software label, which he named GT Interactive, manufactured an extraordinary 600,000 copies of DOOM II prior to its release, marking by far the largest initial production run in the history of computer gaming to date.

In marked contrast to the simple uploading of the first episode of the original DOOM, DOOM II was launched with all the pomp and circumstance that $2 million could provide. A party to commemorate the event took place on October 10, 1994, at a hip Gothic night club in New York City which had been re-decorated in a predictably gory manner. The party even came complete with protesters against the game’s violence, to add that delicious note of controversy that any group of rock stars worth their salt requires.

At the party, a fellow named Bob Huntley, owner of a small Houston software company, foisted a disk on John Romero containing “The Dial-Up Wide-Area Network Games Operation,” or “DWANGO.” Using it, you could dial into Huntley’s Houston server at any time to play a pick-up game of DOOM deathmatch with a stranger who might happen to be on the other side of the world. Romero expressed his love for the concept in his trademark profane logorrhea: “I like staying up late and I want to play people whenever the fuck I want to and I don’t want to have to wake up my buddy at three in the morning and go, ‘Hey, uh, you wanna get your skull cracked?’ This is the thing that you can dial into and just play!” He convinced the other id boys to give DWANGO their official endorsement, and the service went live within weeks. For just $8.96 per month, you could now deathmatch any time you wanted. And thus another indelible piece of modern gaming culture, as well as a milestone in the cultural history of the Internet, fell into place.

DOOM was becoming not just a way of gaming but a way of life, one that left little space in the hearts of its most committed adherents for anything else. Some say that gaming became better after DOOM, some that it became worse. One thing that everyone can agree on, however, is that it changed; it’s by no means unreasonable to divide the entire history of computer gaming into pre-DOOM and post-DOOM eras. Next time, then, in the concluding article of this series, we’ll do our best to come to terms with that seismic shift.

(Sources: the books Masters of Doom by David Kushner, Game Engine Black Book: Wolfenstein 3D and Game Engine Black Book: DOOM by Fabien Sanglard, and Principles of Three-Dimensional Computer Animation by Michael O’Rourke; Retro Gamer 75; Game Developer premiere issue and issues of June 1994 and February/March 1995; Computer Gaming World of July 1993, March 1994, July 1994, August 1994, September 1994. Online sources include “Apogee: Where Wolfenstein Got Its Start” by Chris Plante at Polygon, “Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Era of First-Person Shooters” by David L. Craddock at Shack News, Benj Edwards’s interview with Scott Miller for Gamasutra, Jeremy Peels’s interview with John Romero for PC Games N, and Jay Wilbur’s old Usenet posts, which can now be accessed via Google Groups. And a special thanks to Alex Sarosi, better known in our comment threads as Lt. Nitpicker, for pointing out to me out how important Jay Wilbur’s anything-goes approach to distribution of the free episode of DOOM was to the game’s success.

The original Doom episodes and Doom II are available as digital purchases on GOG.com.)

Original URL: https://www.filfre.net/2020/06/the-shareware-scene-part-4-doom/