From Tales of the Rampant Coyote

Posted by Rampant Coyote on September 4, 2018

I grew up reading stories from the “pulp era.” I also grew up playing Dungeons & Dragons (well, once I turned 12… so reading predated the playing by a little bit). Until I read Appendix N by Jeffro Johnson, I didn’t realize there was a connection between the two. When I first started playing D&D, it was pretty much “anything goes.” Science fiction, fantasy, horror, whatever… it all worked. Old-school D&D was like that… as was old-school pulp. I didn’t consciously realize this, it was just the attitude reflected in the rules and game modules, in the articles and letters in Dragon magazine, Polyhedron, and similar periodicals (ah, the days before the Internet). It was on the covers of Heavy Metal and White Dwarf magazine. And it was part of my favorite films, the original Star Wars trilogy, featuring space wizards with magic swords battling it out with space ships and giant walking robots blasting it out in the background. Awesome stuff.

At some point, I became a purist. Fantasy was fantasy and science fiction. I sneered at an aquantance’s D&D campaign that featured knights wearing powered space-armor and lasers. Nevermind the fact that I’d had plenty of fun years earlier playing the science-fiction-themed official D&D module, “Expedition to the Barrier Peaks,” or that I still used the totally broken SF-themed psionics rules for 1st edition Advanced D&D. At this point, young Jay Barnson thought he knew everything about everything, and damn it, science fiction was different from fantasy! I resented how the later entries in the Wizardry computer game series (and the early Might & Magic titles) mixed space ships & magic. How silly! Okay, maybe they weren’t handled well, but I was against the principle!

And then I got older. More experienced. Played more games, watched more films, read more fiction both modern and classic. And the voice inside my head finally said, “Screw it.” Probably the same voice that heard Clarke’s Third Law too many times: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I realized the wall between science fiction and fantasy was a lot thinner than I’d thought. Where had it come from?

The answer is, in part, John W. Campbell. A science fiction author to who took the helm of Astounding Stories (formerly Astounding Stories of Super Science) in 1938, changed its name to Astounding Science Fiction, and emphasized science-driven stories as opposed to pulp adventure stories with vaguely scientific rationale to make the plot work. This wasn’t entirely a new approach. That wasn’t too dissimilar to Hugo Gernsback’s approach with launching Amazing Stories more than a decade before. Interestingly enough, by this point, this marketing decision set Astounding Science Fiction apart from Amazing Stories, which was in my perspective the point. Campbell made the focus on harder science stick, in part because he paid top dollar for stories, compared to the rest of the pulp market.

Campbell ran the magazine for a long time afterward, eventually dropping the “Astounding” and rebranding it “Analog,” the name by which it is known today. But the beginning of his tenure marked what is frequently called the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.” This all came at the right time, as the severe belt-tightening of the Great Depression came to a close, and the specter of World War II arose. People were desperate for an inexpensive escape, and pulp adventures filled the bill nicely. The relative optimism of science fiction of the era didn’t hurt. The idea that men with screwdrivers could engineer solutions to seemingly insurmountable evils as well as any hard-hitting action hero was refreshing and welcome. Campbell’s marketing focus came at a good time. Science fiction grew in popularity, and other magazines sprang up emphasizing science fiction with various levels of Campbellian “hardness.”

It is my belief that this exerted a pretty strong influence over the writing community. As a writer, you need to maximize your chances of both making a sale and selling to the highest-paying markets. It’s how you put food on the table. Since the “slicks” rarely purchased stories with unrealistic elements, your best bet would be to target Astounding and to try and meet Campbell’s standards. Even if you were rejected, you could then submit elsewhere. Amazing Stories might still publish something that felt like an Astounding story, but the converse was not true. So the “Golden Age” erected a wall between “Science Fiction” and everything else. If you didn’t meet Campbell’s standards, not only was your story not Astounding material, but it might not even *gasp* be science fiction at all! Oh, noes!

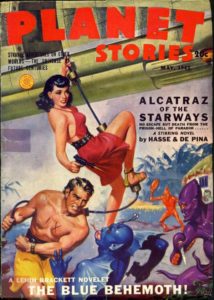

That didn’t stop Planet Stories or Amazing Stories from publishing all kinds of character-driven tales of space princesses and heroic derring-do throughout the solar system and galaxy at large, or calling it science fiction. So it wasn’t a universal change. Snobbish readers referred to these “other” stories as “Space Opera,” hoping to smear it with association to “Soap Operas” and “Horse Operas,” but today the description has lost most of its negative connotation. So there. The assumption persists that the harder SF of Campbell’s tenure was superior and more “mature” than that of the earlier or competing pulps.

That didn’t stop Planet Stories or Amazing Stories from publishing all kinds of character-driven tales of space princesses and heroic derring-do throughout the solar system and galaxy at large, or calling it science fiction. So it wasn’t a universal change. Snobbish readers referred to these “other” stories as “Space Opera,” hoping to smear it with association to “Soap Operas” and “Horse Operas,” but today the description has lost most of its negative connotation. So there. The assumption persists that the harder SF of Campbell’s tenure was superior and more “mature” than that of the earlier or competing pulps.

At once point, the assumption was almost uncontested, but there’s vocal disagreement today. But that’s only by the people who actually read those older stories…

But that’s primarily where the modern division between science fiction and fantasy came from. The “Golden Age” was a golden wall. Was it a good thing? I’m not sure. For me, I think it was a good thing insofar as it gave a boost to “hard” science fiction, yet remained porous and easily crossed. Where it caused the snobbishness and this idea that fantasy chocolate and science-fiction peanut butter should never be mixed, maybe it wasn’t so great. For my part, most of the science fiction I’ve read came after Campbell began his reign, and there’s a lot I love. Some of that might never have been written had Campbell not encouraged it through his high bounty on hard SF.

But then, what is “hard” SF? What qualifies? Honestly, a lot of the stuff that seemed pretty hard back in the day and tied into then-modern theories of how the universe worked come off as being pretty bizarre and fantastic today. A lot of the stuff written in the mid-20th century is alternate history today, dealing with timelines that never came to pass, theories long disproven, and mixing antiquated technology with things that still don’t exist. Even Andy Weir’s “The Martian,” a recent classic of hard science fiction that has enjoyed well-deserved mass-market popularity, is starting to feel a little quaint with the latest science and technology. When I was a kid, planets were thought to be rare, and dinosaurs didn’t have feathers. Science is a journey and methodology, not a destination. This makes it ripe for imaginative stories, but not so great for hard divisions between it and fantasy.

But I’m all for fuzzy, blurred lines, inviting all kinds of variety across the spectrum by virtue of their existence. I don’t want to argue about whether Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s godlike Q or premise of “we’ve evolved past needing money” is more or less fantastical than the Jedi and the really strange size / distance scales of Star Wars. I don’t think The Martian or Interstellar are inherently superior to Guardians of the Galaxy or Wonder Woman by virtue their scientific plausibility. I want stories in the middle and at the extremes.

But I’m all for fuzzy, blurred lines, inviting all kinds of variety across the spectrum by virtue of their existence. I don’t want to argue about whether Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s godlike Q or premise of “we’ve evolved past needing money” is more or less fantastical than the Jedi and the really strange size / distance scales of Star Wars. I don’t think The Martian or Interstellar are inherently superior to Guardians of the Galaxy or Wonder Woman by virtue their scientific plausibility. I want stories in the middle and at the extremes.

And yeah, I’m okay with D&D games with powered battle-armor, and with the Dark Savant orbiting a fantasy world in a space ship. It’s all good fun.

Filed Under: Books, Dice & Paper, Retro – Comments:

Original URL: http://rampantgames.com/blog/?p=12073