From The CRPG Addict

|

| The title shows that, just as with The Game of Dungeons, “DND” was just a file name, not the game name. |

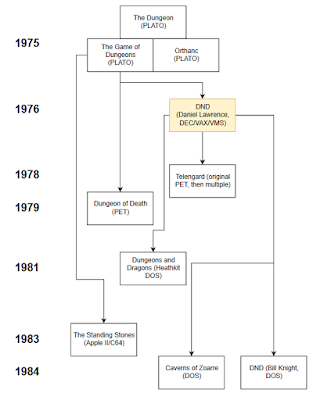

Ahab did a great job in the last couple of years analyzing The Dungeon and The Game of Dungeons, prompting me to go back and win those games. But those contributions pale in comparison to what he did last month. For the first time that I’m aware of, he figured out how to get a version of Daniel Lawrence’s DND operating on a VAX emulator. For decades, we’ve had to reconstruct this missing link between the PLATO Game of Dungeons and the commercial Telengard based on player memories, adaptations, and interpretations of source code. Ahab not only showed the game in action, but he won it and supplied a full set of maps (for one of the three dungeons) as part of the process. His material is key to understanding this particular, peculiar line of CRPGs. Among other things, the ability to actually play this game shows that only the file name was DND; the title was–copyrights be damned–Dungeons & Dragons.

|

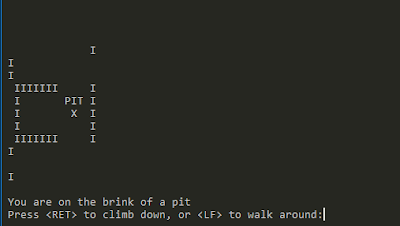

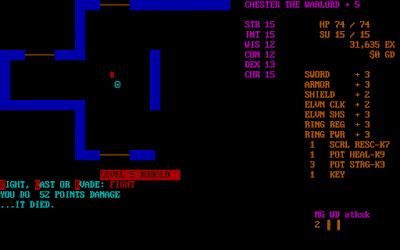

| Gameplay in the VMS/VAX DND. My graphics are all messed up because of a line feed issue that I can’t solve. The dungeon walls don’t really look this chaotic. |

Untangling the history of this particular lineage has been difficult, largely because of horrendous misinformation, much of it perpetrated (or at least not corrected) by Lawrence himself, who died in 2010 at the age of 52. (Among other things, he explicitly designated this page, which is so hopelessly confused I don’t know where to begin, as the “official DND site.” The authors do deserve credit for aggregating and preserving important files.) To read some sites, Lawrence is the father of the entire CRPG line, having written the first DND as early as 1972–two years before tabletop Dungeons & Dragons! His game was so popular, some articles have alleged, that students at the University of Indiana decided to adapt it as The Game of Dungeons. (Of course, it was the other way around.) Even writers who haven’t so thoroughly confused the timeline have accepted Lawrence’s assertions that he wrote “his” DND entirely on his own, with no reference to any other game, despite that it clearly borrows elements from the PLATO Game of Dungeons and Lawrence went to a university (Purdue) connected to PLATO. In a 2007 interview with Matt Barton, he suggests that his “play testers” might have played The Game of Dungeons and brought ideas to him. To me, such a scenario doesn’t begin to explain the similarities between the games.

|

| Daniel Lawrence in an undated photograph. Credit unknown. |

The best truth that I can determine with the available evidence is that Lawrence wrote his first version of DND in 1976 or 1977, clearly after being exposed to The Game of Dungeons on PLATO. I’m inclined to think that 1977 is the more likely date, since DND is closer in similarity to Version 6 of The Game of Dungeons, which wasn’t released until 1977. Then again, elements of The Game Version 8 (1978) also seem to show up in Lawrence’s work, so it’s possible he went back to the well several times during the development of his adaptation. The existence of several mainframe versions would support this thesis.

As we’ll see, Lawrence made plenty of additions, and to recognize that he plagiarized from The Game is not to deny his own skill and innovations. His primary contribution was releasing the game to the wider world, first by writing a version for Purdue’s DEC RSTS/E system. (In Lawrence’s own words, the game was “the cause of more than one student dropping out” and “made me very unpopular with the computing staff at Purdue.”) Engineers from DEC maintaining Purdue’s system became familiar with the game and liked it so much that in 1979, they asked Lawrence to come to their Massachusetts headquarters and write a port for DEC’s PDP-10 mainframe running the TOPS-20 operating system. (There are hints within DEC documents that Lawrence may have been paid for this, and that DEC’s intention was to offer the game with its installations. The specific agreement between Lawrence and DEC has not come to light.) This version was subsequently disseminated in many locations where DECs were installed. The VMS/VAX version that Ahab got running seems to have been ported from this mainframe version.

By then, Lawrence had already been porting the game to the micro-computer. In 1978, he wrote a version for the Commodore PET that he titled Telengard, which had been the name of one of the explorable dungeons in DND. Representatives from Avalon Hill ran into Lawrence demoing the game at a convention in 1980 or 1981 and offered him a publishing deal, which ultimately saw PET, Commodore 64, Apple II, TRS-80, Atari 800, and MS-DOS releases starting in 1981 or 1982.

|

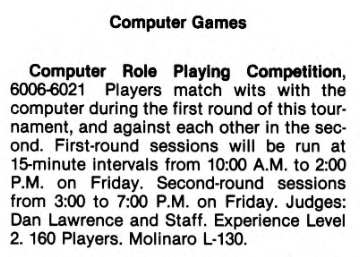

| The title screen from the Commodore PET version of Telengard. The 1981 date seems unlikely as the actual release year. |

(None of the histories of Lawrence or Telengard mention the specific convention at which this meeting occurred, but I found a likely session in the GenCon XIV program from August 1981. Unless Lawrence ran the same competition multiple years [I can’t find the previous year’s catalog], it seems unlikely that Telengard had a pre-1982 release date despite the copyright date on some versions of the game.)

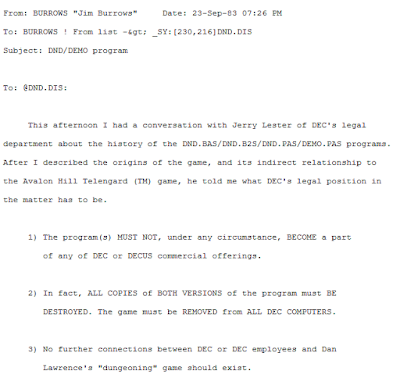

From then on, Lawrence and Avalon Hill waged war on the ubiquitously-released free versions of the game, ordering their removal from every system on which they appeared. For its part, DEC acceded to legal threats from Avalon Hill, resulting in the modern difficulty reconstructing what those early versions looked like. You can read a long, fun e-mail chain here in which DEC employees try to argue law with their own legal department. Hilariously, various employees request assistance in finding the Orb throughout the thread while their exasperated bosses remind them that the game isn’t supposed to exist on any DEC machine anymore.

|

| A DEC executive orders the deletion of DND from DEC machines. |

If Lawrence was guilty of some disingenuous behavior in trying to quash free versions of a game he partly plagiarized, it came back to bite him in repeated plagiarisms of his versions. We’ve seen plenty of them on this blog, including the so-called “Heathkit DND” (in actuality, also titled Dungeons and Dragons) of 1981, R.O. Software’s DND (1984), and Thomas Hanlin’s Caverns of Zoarre (1984). There are other BBS and shareware versions of the game that we haven’t tried.

|

| A DND “family tree.” |

That’s the history. But what is Dungeons & Dragons? It’s a text-based game with ASCII graphics in which a single character navigates one of three 20-level dungeons in a quest to retrieve a magic orb from a dragon. The layout of the dungeon and the locations of many of the special encounters are fixed, but the locations of combats and miscellaneous treasure finds are so random that you could encounter a never-ending stream of them from the same dungeon square. Combats are with a small menagerie of enemies, each with different strengths and vulnerabilities to the game’s various spells. The character gains experience through both combat and treasure-finding, with miscellaneous encounters increasing and decreasing his attributes and providing him with magical gear. When he feels strong enough, he takes on the final dungeon level, recovers the orb, and–if he makes it back alive–gets his name on a leaderboard of “orb finders.”

As I mentioned, there are too many elements copied directly from The Game of Dungeons for it to be remotely possible that Lawrence never saw it. These include:

- The basic approach to game mechanics and goals, including the existence of permadeath.

- A character creation process that includes a “secret name” for each character, serving as a kind of password

|

| The need for a “secret name” is drawn from The Game of Dungeons, but the full set of attributes, the choice of character classes, and the choice of dungeons is new to DND. |

- The number of dungeon levels.

- A main quest to recover an orb.

- Carrying treasure out of the dungeon converts it to experience points.

|

| My character levels up from a treasure haul. |

- A list of successful characters called “finders.”

- The existence of a transportation device, called “Excelsior,” that moves you among the levels.

- Basic combat options of (F)ight, (C)ast, and (E)vade.

- A small number of monsters who have numeric levels assigned.

- Many of the magic items are identical. Items can be trapped (although Lawrence’s traps are more creative).

- Treasure is found in both chests and random piles. Chests contain vastly more gold than the random piles.

- Magic books that can raise or lower your attributes.

|

| DND’s handling of chests and books is the same as The Game of Dungeons. |

- Pits that you can fall down, dumping you on lower levels.

|

| Luckily, I spotted this one. |

It’s also possible that Lawrence took a few elements from the earlier The Dungeon, including the organization of spells into a number of “slots” per level as well as some of the treasures you can find in the dungeon and their relative conversion to gold.

But Lawrence also added some new things to the Game of Dungeons template, some making it better, some making it poorer. These include:

- DND has no graphics. Walls and corridors are ASCII characters and the main characters is represented as an X. The Game of Dungeons had graphics for geography, the PC, monsters, equipment, gold, and so forth.

- Instead of just “gold,” the player finds a variety of different treasure types that are converted to gold.

- DND dungeon levels are much larger.

- The Excelsior transporter exists on every level in DND, not just the top one.

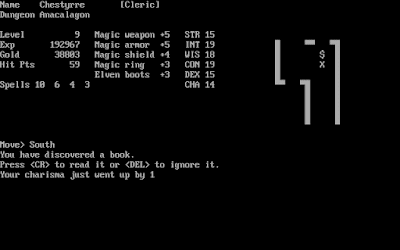

- A full set of tabletop Dungeons and Dragons attributes. The Game of Dungeons just had strength, intelligence, and dexterity. DND adds constitution and charisma.

|

| A DND “character sheet.” |

- While the character in Game was a multi-classed fighter/magic-user/cleric, DND has the player specify a choice of these classes. As such, combat is rebalanced so that you don’t need to cast particular spells to ensure victory, and a pure fighter has a shot at winning. Spells, which could reliably one-shot certain enemies in The Game, are significantly reduced in power. They’re also more in line with tabletop Dungeons and Dragons and, it must be said, a lot less silly than The Game.

- There’s no distinction between experience and gold in DND, as there was in Game through Version 5. The Game also changed to a single experience pool starting in Version 6, so Lawrence may have been influenced by the later one.

- DND offers three dungeons to explore–Telengard, Svhenk’s Lair, and Lamorte–each of which might contain the orb.

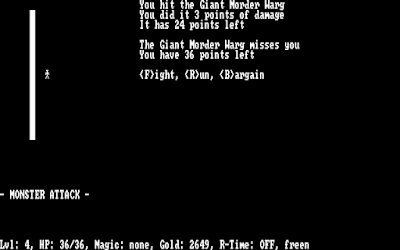

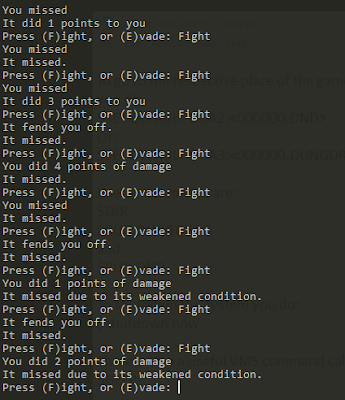

- Game resolved combats all at once. DND shows round-for-round results.

|

| DND’s approach is generally better, but sometimes you wish it would just hurry up and get it done. |

- DND completely randomizes the appearance of treasure. The Game “seeded” each level with gold and chests whenever you entered, and you could clear the level, but in DND, treasure has a chance of showing up in every square as you move to it, including those you’ve already explored.

- DND adds more special encounters at fixed locations, including thrones, altars, fountains, dragons’ lairs, and doors with combination codes.

|

| Special encounters with altars are a new element in DND. |

- Lawrence replaced the awkward “teleporters” with stairs that remain in a fixed location.

- DND includes a greater variety of equipment, including magic weapons other than swords. The pluses go much higher, too. Where The Game capped at +3, DND allows higher than +20.

- DND adds cute atmospheric messages as you explore. Examples: “A mutilated body lies on the floor nearby”; “‘Turn back!!!’ a voice screams”; “The room vibrates as if an army is passing by.” There’s even a reference to Colossal Cave Adventure and its hollow voice that says “PLUGH.”

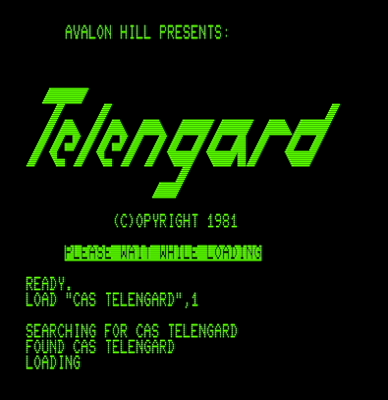

Finally, it’s worth noting some of the changes between DND and Telengard:

- Telengard has no main quest. The only objective is to get stronger and richer. For years, I thought this was a defining feature of the sub-genre, but it turns out that it’s actually quite rare. Most variants have some kind of main quest.

- Telengard‘s has only one dungeon, randomly drawn every time you start a new game.

- The appearance of thrones, fountains, altars, and other special features are completely randomized, just like monsters and miscellaneous treasure. A player can encounter everything that Telengard has to offer by passing time in a single square.

- Telengard has graphics.

- Telengard has an expanded selection of items, including potions and scrolls.

|

| Telengard is a nicer-looking game, but the greater randomization creates a chaotic experience. |

|

| Gameplay from the Heathkit Dungeons and Dragons (1981). |

|

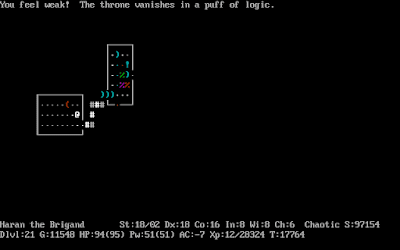

| Sitting on thrones in NetHack has many of the same consequences as in DND. |

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/02/the-final-word-on-daniel-lawrences-dnd.html