From The CRPG Addict

|

| Trying the Atari ST version this time. |

Difficulty: Hard (4/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

Wizard Warz isn’t much of an RPG, although I suppose it technically qualifies. (For some reason, I had the opposite opinion in 2011.) One of the things that must have thrown me is that there’s no character creation process, aside from selecting your sex and opening batch of spells. Then you’re thrown onto the landscape, an apprentice wizard tasked with developing his skills and ultimately freeing the land from the yoke of seven powerful wizards.

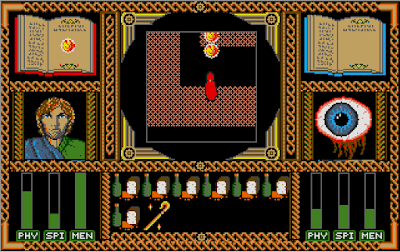

The plot and its different phases are just an excuse for a near-endless series of one-on-one combats between you and the other wizards. Every enemy in the game, no matter what it is nominally called–animal, plant, human, supernatural–just looks like a little wizard in a cloak when combat begins. Every enemy has the same types of spells that you do. In combat, you fire spells at each other to lower each other’s physical, spiritual, and mental meters. If any of these reaches 0, you die.

|

| Locked in combat with a werewolf. |

The game progresses in three phases. During character creation, you choose four spells that you’ll use for the first phase. You then run around an island fighting six creatures: ape (or maybe yeti), spider, scorpion, werewolf, triffid, and serpent. (These might vary by platform.) Upon victory, each gives you an artifact: crown, cape, sword, chalice, pocket watch, and key. By returning these artifacts to the various castles and towns on the island, you receive food in return. Once you’ve returned all six, the first phase is over and you enter a port town for passage to the next location.

|

| Returning an item to the castle in exchange for bread. |

Phase 2 puts you in an arena where you can select from 30 potential opponents from the standard high-fantasy menagerie (e.g., troll, vampire, giant wasp, zombie, gorgon, dwarf, dragon), defeating them one by one. Most victories allow you a new spell (up to 9) or an attribute bump. Four victories give you a familiar, which offers a permanent advantage like shrugging off certain spells. Three of the victories give you a sword, a ring, and wand. Once you have all three of these, you move on to Phase 3.

|

| Phase 2 lets you choose your opponents, cycling through them with the joystick trigger. This one is best dealt with via physical spells. |

When I played in 2011, I died in Phase 2 after defeating most of the monsters because I ended up fighting a sorceress who had the “Forget” spell. “Forget” causes your active spell to disappear from your spellbook, and if you’ve played stupidly (i.e., if that was your only offensive spell), you could end up dead in the water like I was. But back in 2011, I apparently hadn’t found the game manual, which offers several options to defend against this fate (particularly “Neutralize Magic,” but I particularly like “Mirror,” which causes the opponent to forget his own “Forget”). You can also carefully plot your way through the enemies, saving those with “Forget” for later in the phase–and perhaps never meeting them at all, if you get the three items first.

|

| A timely reward for defeating a medusa. |

Phase 3 has you take on the seven evil wizards in succession: Wolf Lord, Bear Lord, Imp Lord, Ogre Lord, Gryphon Lord, Crystal Lord, and Dragon Lord. You have to fight several of their henchmen before the wizards themselves appear. Every enemy you kill during this phase rewards you with food, which you can use to replenish physical health. Once you defeat the final wizard, you win.

|

| Finding the Wolf Lord in the third phase. Note how the character’s face changes as he gets more experience. |

If it sounds boring, there is theoretically quite a bit of variance in tactics depending on the “wizard” you face. The game manual tells you what spells each type of wizard favors, and you can match your own spell in kind. Particularly during Phases 2 and 3, there are enemies that only respond to certain types of damage, so you cannot for instance rely on physical spells against most undead creatures. You can also tailor various types of defensive spells to their attacks.

But, yes, an awful lot of the game can be completed by simply spamming your most powerful physical spell the moment you see the enemy. I favored a combination where I would hit the enemy with “Slow” or “Stun” and then launch a succession of “Fireballs” or “Magic Missiles.” This worked against all but a few creatures for which I needed “Heavenly Bolt” (a spiritual spell) or “Mindwrack” (a mental spell). When you shoot a spell, you have to be aligned right for it to hit the enemy, so a lot depends on your own controller dexterity.

The game does some odd things with the three meters, which are both measures of health and reservoirs of spell points. First, physical health drains a little bit as you walk around, and particularly if you bump into things. Second, it’s nearly impossible to replenish mental energy and spiritual energy. You can transfer mental energy to spiritual energy with a key, and also spiritual energy to physical energy. Food, meanwhile, replenishes only physical energy. The only way you get mental energy replenished is as a reward for phase completion or for some of the Phase 2 combats. Any player who decides to specialize in mental spells is in for a tough game, and it’s a mystery why the developers didn’t better balance these abilities. It would make perfect sense if there was a key that completed the loop by transferring physical energy to mental energy, but there isn’t.

|

| Nearing a scorpion in Phase 1. He responds only to physical damage. Fortunately, spiritual and mental energy can be exchanged for physical energy. |

The particularly crazy thing about Wizard Warz is that a complete game takes at least a couple of hours, and yet there’s no way to save. It also means that even though the individual combats aren’t difficult, the accumulation of them–you have to fight over 60 battles to win the game–makes it hard to ensure that something doesn’t go wrong. The game could have autosaved at the beginning of each phase to maintain some of the difficulty but keep it fair.

Aside from the lack of save ability, there are a couple of fatal flaws. First, despite wildly different graphics in the various versions, it apparently only shipped with a single set of instructions. The instructions show which graphic goes with which spell, but for many versions of the game, the in-game graphics for the spells look very little like those in the instructions. This makes it difficult to tell what spell the enemy mages are using against you, and what spells are being offered to you after the combats in Phase 2. Second, and most important, the exploration window is laughably small (just about every review commented on this). It makes it hard to find opponents and (in Phase 1) towns, and it also means that during the battles, the two combatants are practically in melee range as they hurl spells at each other.

|

| Blasting fireballs at an off-screen enemy. |

The game is also bugged. In particular, none of the familiars seem to do what they’re supposed to do. One of them is supposed to expand the size of the map window, but nothing seems to change. Others are supposed to protect you against “Stun,” “Forget,” and “Fear.” I can’t say for sure they don’t work because I’m not sure I was subjected to those spells after getting the familiars, but magazines at the time reported that they didn’t work.

Most bugged of all is the victory. I got to the ending on my own and watched two YouTube videos of the endings on different platforms, but I still haven’t seen the final screen as originally intended. In the ZX Spectrum edition, the game just froze when the player defeated the final wizard. In the Amiga version, the player got a “congratulations” screen at the end, but it told him that he’d only completed 11% of the game and that he’d only achieved the rank of “apprentice.” Meanwhile, in my experience with the Atari ST, nothing happened after I defeated the final wizard and I was able to keep running around the map. If I killed myself, I got a message that I had completed 100% of the game, and that I had achieved a grade of “X Erase,” which is text from the instructions. Incidentally, the game had made my character invisible for the last 20 or so minutes of gameplay (not in battle, but on the outdoor map).

|

| My “winning” screen. |

Wizard Warz was developed in the mid-1980s in Britain, where most of the RPGs from local studios were highly original, utterly uninfluenced by American titles of the same period, and still not very good. As with games like Heavy on the Magick and Swords and Sorcery, I find myself noting that no other game has taken this particular approach–and then wishing that it had been more derivative. But even allowing for standard British RPG unorthodoxy, it’s hard to imagine that anyone thought this game was going to be a blockbuster. And yet the developers (Canvas Software) simultaneously released it on five different platforms, with a sixth following within a year.

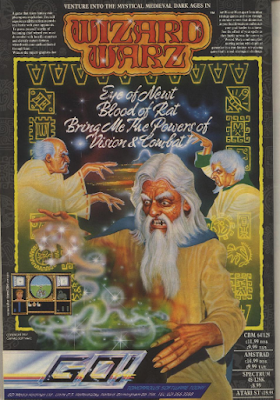

Although the structure, commands, and screen layout are the same across its various platforms, the graphics couldn’t be more different. Sure, they had to adapt to what the platforms were capable of, but it feels like they didn’t re-use any assets at all. They didn’t even multi-task the staff: across the six versions are four different lead programmers and four different graphic artists. The box shows solid production values, and the ads rival those for AAA games of the same period. Why did Canvas go all-in on Wizard Warz?

|

| DOS. |

|

| Commodore 64. |

|

| ZX Spectrum. |

An equal mystery is where Wizard Warz came from in the first place. Canvas mostly specialized in ports for other companies. (In my 2011 entry, before I had any idea how to research properly, I credited them with the famous Airborne Ranger, but they just did ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC ports. I mean, if they had developed it, it would have been British Special Forces or something.) Their in-house games were odd action adaptations of Highlander (1986) and Miami Vice (1986). They had no particular RPG experience or even fantasy experience.

Lead design is credited to a Gary Bolton, who has only three games to his credit. The second is Starring Charlie Chaplin (1988), a unique and absolutely unclassifiable game in which you control the famed comedian, pratfalling your way around a movie studio before you cut and edit the result and see how it does at the box office. He also has a producer credit on an Atari ST port of Atari’s Road Runner (1987). (I tried unsuccessfully to find Bolton for this review. I did write to another former Canvas employee but got no response.)

|

| The ad promises a livelier experience than the game was capable of delivering. |

Whatever dreams they had for Wizard Warz, the game didn’t save the company: it went out of business in 1988 or 1989. The game’s best review was a 77/100 from July 1988’s Sinclair User. It’s one of those baffling British reviews where you wonder if the author played the same game. I can kind-of understand his praise for the graphics–he’s comparing it to other ZX Spectrum games, after all–but not the part where he’s bored because he spent too much time “wandering around without knowing where one’s next quest is coming from.” I don’t even know how to respond to that. The only “wandering” that can be done in the game is on the small game maps, and if you can’t find the “next quest” on those, you’re the kind of person who needs a map to get out of a half-bath.

Your Sinclair, covering the same version, was harsh (“one of the least fun pieces of programming we’ve had the misfortune to play in months”). ACE was lukewarm at 62/100 (“as RPGs go, it’s nothing outstanding”). Continental magazines put it in the 30s and 40s. The worst review was from Zzap!, which gave 30/100 for the C64 version, which admittedly had the worst graphics. (I also couldn’t get the controls to work.) But the fact that it was reviewed by so many magazines in the first place testifies to its wide release and, thus, expectations.

I looked over my review of 2011 and decided I was too generous on “equipment” (you really only have food, in terms of usable stuff) but perhaps didn’t give enough credit to “magic and combat.” I was probably thinking of the spell as a type of “equipment.” I don’t know why I gave it a 3 for “quests”; any game that offers only a main quest with no side quests or choices gets only a 2. My changes bring it down to a 15 from the original 17 score I’d given it. But more important, I get to change my loss to a win, which was enough to get me an extra percentage point in the sidebar.

Alas, I’m running out of low-hanging fruit in the previously-lost list. Winning Bones (1991) should only take an hour if I can figure out what I did wrong the first time. War in Middle Earth (1988) also shouldn’t be that hard; I should have won it before deciding it wasn’t an RPG and dismissing it. Seven Spirits of Ra (1987) might be worth another look. Beyond that, there are good reasons I abandoned those games, and any return is not only going to be time-intensive, but it will be time spent on a game I already know I don’t like or is very difficult to win. That time is probably best spent moving forward, so don’t look for a lot more of these.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/06/revisiting-wizard-warz-1987.html