From The CRPG Addict

|

| The first attempt at a history of a troubled company. |

Our tour through the games developed and published by Paragon software has included some highly-original (if not highly-rated) titles, including Alien Fires: 2199 A.D. (1987), Wizard Wars (1988), MegaTraveller 1: The Zhodani Conspiracy (1990), Space 1889 (1990), MegaTraveller 2: Quest for the Ancients (1991), Twilight: 2000 (1991), and most recently Challenge of the Five Realms (1992), developed as Paragon was being purchased by MicroProse. Very little has been written about the history of Paragon, so I spoke to co-founder and game designer F. J. Lennon to get to the bottom of the many questions that were generated during my experience with this series. In addition, I bought and read Lennon’s business book, Every Mistake in the Book: A Business How-NOT-To (2001), which informed my coverage below.

Beginnings

Paragon Software began in 1986 in a St. Vincent College dorm room in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, co-founded by Mark Seremet, Anthony Davies, and Francis Joseph Lennon III, who has always gone by his initials, “F. J.” The students originally started the company to make accounting software, and they released at least one title for the Commodore 128. (Davies was gone before the first title hit the shelves.) But the entrepreneurs behind the company were also fond of playing Karate Champ at their local pizza parlor, and they began to discuss how they could bring such a game to the microcomputer. The result was Master Ninja: Shadow Warrior of Death (1986) for the Amiga and Commodore 64.

(MobyGames lists a contemporary title from the company as Gemini-2 from 1986, but this was developed by an independent Mississippi developer who also briefly used the name “Paragon Software.” The companies are unconnected.)

The Paragon principals were exhibiting

Master Ninja at the 1987 Computer Electronics Show in Chicago when Jeff Simpson and Sky Matthews wandered up. The pair had created

Alien Fires: 2199 A.D. for the Amiga and were looking for a publisher. “I don’t know if there was much of a game there,” Lennon recalls, “But it was dazzling to look at. Breathtaking.” (Recall from

my coverage that the game had digitized sound, highly original graphics, and incremental movement.) Simpson and Matthews, who were about the same age as their Paragon counterparts, struck up a fast friendship and soon the developers had a publishing deal.

|

I will always remember Alien Fires for Mangle-Tangle (or was it Mango-Tango?), the pipe-smoking kangaroo/rabbit/horse.

|

1988 saw Paragon produce two text adventures–Guardians of Infinity: To Save Kennedy and Twilight’s Ransom. (The latter was notably set in “Liberty City,” which would of course be the setting for a later Grand Theft Auto title.) The same year, Mark Seremet and Christopher Straka designed Wizard Wars. (Straka, a martial arts expert, had been hired to perform karate moves as a reference for the Karate Champ animators. Afterwards, according to Lennon, “he just hung around and worked his way into a design role.” Two years later, he and Thomas Holmes staged a “mutiny” and left Paragon to form Event Horizon, later DreamForge.) I mentioned to Lennon how terrible I thought Wizard Wars was, and he conceded that while Seremet was “a really great programmer, he was never much of a creative.” Lennon himself was “never a coder,” and thus fell into a more natural roll as the top-level designer, writer, and team-leader.

Deals

In his book, Lennon characterizes these early years unromantically. Paragon was constantly living hand-to-mouth, maxing out its lines of credit, shucking and jiving its investors, running on outdated PCs, at first cramped in an apartment, then subjected to a flood and a burglary when they finally got their own offices, with no clear delineation of responsibilities and few explicit goals and timelines.

Guardians of Infinity was a horrible disaster, selling fewer than 1,000 copies; Lennon admits that he wrote the game for himself rather than responding to what the market clearly wanted.

The company might not have lasted long if it had not received a license to create PC games based on Marvel Comics properties. I had long wondered how Paragon, a company with a spotty history of not that many titles, had come to acquire such a valuable property. “It was as simple as walking in and asking them,” Lennon said. “No one had gotten there first.” (In his book, Lennon also confesses to possessing a certain bravado that led to publishing deals that the company should not otherwise been able to achieve.) Their deal with Marvel led to

X-Men (1989),

The Amazing Spider-Man and Captain America in Dr. Doom’s Revenge! (1989),

The Punisher (1990),

The Amazing Spider-Man (1990), and

X-Men II: The Fall of the Mutants (1991).

|

| Paragon’s action/adventure titles based on Marvel properties used an interface similar to the later GDW-based RPGs. |

The round of press following the acquisition of the license put Paragon on the map. MicroProse, not too far away in Maryland, called about a distribution deal. More important for our purposes, at the 1989 Gen Con convention, they were approached by Marc Miller of Game Designers’ Workshop about developing the GDW properties into games. “I hit it off with Marc Miller pretty quickly,” Lennon recalls. Both men had a proficiency for story-telling and world-building.

I asked about the pace of development–four major RPGs in two years, while half the company was working on the Marvel properties. To my surprise, it turned out that the pace had nothing to do with GDW. Instead, MicroProse set the timetable. “They would tell us that we needed one adventure game and two RPGs by Christmas,” Lennon offered as an example. Until speaking to Lennon, I didn’t realize how much control the publisher had over the development schedule. I guess I rather assumed that the developers worked at whatever pace they wanted until the game was ready for a box and a manual. I couldn’t have been more wrong; publishers had the power to break developers. “Everything had to be done by Christmas or you were dead.”

The GDW Titles

Paragon’s first title under the Game Designers’ Workshop deal was

MegaTraveller 1: The Zhodani Conspiracy (1990). Reviews of the game were actually mixed (British Amiga magazines loved it), but Lennon recalls them universally negative. “We got skewered. We were lucky we rebounded from that.” He remembers the real-time combat being a particular point of contention for fans of the tabletop game. He recalls

Computer Gaming World editor Johnny Wilson, who could “make or break your game,” and who Lennon actually consulted with in his next attempt at a GDW title,

Space 1889.

|

I didn’t like much about MegaTraveller 1, but it had an excellent character creation system.

|

I summarized my own feelings about the titles and their common lack of character development. I had thought that was perhaps a limitation of their source material–the GDW rules–but Lennon recalls that GDW didn’t put much pressure on the team. “Marc Miller recognized that PNP RPGs were not the same as computer RPGs,” Lennon says. He adds that even Marvel didn’t really insist on much input in content and mechanics. “Stan Lee was involved and really interested in the potential of computer games. If he liked something, that’s all you really had to worry about.”

Lennon attributes my complaint more to Paragon’s lack of experience with traditional RPGs. “I don’t know that we really understood the leveling-up process in tabletop games,” he says. “We probably didn’t understand that concept well enough.” Lennon’s own experience with computer RPGs was limited to the

Ultima titles, which themselves lack strong character-development systems for all their world-building prowess.

|

| Space: 1889 had an interesting quasi-steampunk theme, but it was far more an adventure game than an RPG. |

In our discussions, Lennon pointed out something that I probably under-emphasized in my own reviews of the GDW games (and perhaps to some extent,

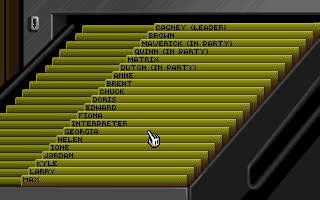

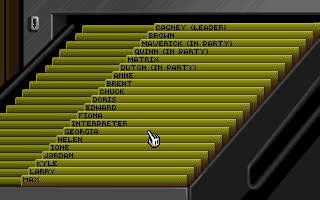

Challenge of the Five Realms): they were designed to flexibly swap out characters. In both the

MegaTraveller games and

Twilight: 2000, you could have a lot more characters in stasis than were active in the party. Players were supposed to regard the beginning of each mission as a puzzle for which they assembled the right team with the right skills. I agree that I didn’t really think about playing the game that way.

|

| Twilight: 2000 let you create 20 characters, so even without “character development,” every skill ought to have someone with a high number. |

In my unkind review of MegaTraveller 2, I wrote:

MegaTraveller 2 is not a good RPG. It fails in every aspect of RPG mechanics, including character development, combat, and equipment. The story isn’t even really that good. Its world-building is minimal. Although you encounter about a dozen races in the game, there’s no real characterization attached to them. And yet this bad sequel to a bad game manages to offer something that no other RPG has offered in the chronology: a truly open world with nonlinear gameplay and dozens of side quests. I would really like to know who on the team insisted on that. He should have been working for a better company.

It turns out that person was Lennon himself. “I remember losing that entire summer,” he recalls of the sequel. “I wrote every line of that dialogue. There were over one thousand NPCs. I probably had two or three thousand pages of documentation and script.” He agreed with me that

Challenge of the Five Realms had more dialogue and text, but he points out he had a much larger team to assist by then, including Laura Kampo, who became (and still is) Lennon’s wife.

|

| MegaTraveller 2 gave us a large galaxy to explore, with plenty of side-quests, NPCs, and intrigue. |

The End

Lennon recalls that the company’s games sold well, but never as well as the companies at the top of the industry, like SSI. GDW, one of its principal partners, “never seemed to be financially healthy.” Their GDW and Marvel licenses expired in 1992. With things looking a bit bleak, Paragon’s owners accepted MicroProse’s offer to acquire the company.

|

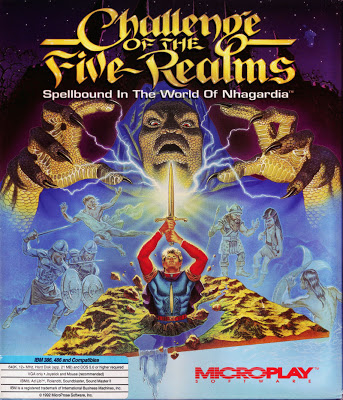

| Challenge of the Five Realms showed what the Paragon team could do without any licensing restrictions. |

Paragon remained mostly intact as a studio within MicroProse and developed Challenge of the Five Realms in 1992 and BloodNet in 1993. GDW’s Miller joined the team to help create Challenge. Lennon remains particularly proud of that game. But it was a bad time to be owned by MicroProse. The company was in serious debt from a failed venture into coin-operated games and from general mismanagement. After a couple of years, Lennon says, the old Paragon team “saw the writing on the wall.”

“We went to [the MicroProse management] and said, ‘we want our studio back.'” Given the parent company’s straits, “They basically gave it back for a ham sandwich as long as we agreed to take on the liability, too.” Having acquired their freedom but no assets, the team readily entered into a partnership with entrepreneur Ryan Brant to form Take Two Interactive, which of course is still going strong.

|

| MicroProse jumped the gun on this ad. |

Lennon himself stayed at Take Two only about two years. He wrote and directed

Star Crusader (1994), co-produced

Hell: A Cyberpunk Thriller (1994), and co-wrote the screenplay for

Ripper (1996). These latter two games were at the forefront of a 1990s trend for real-life cinematics, with high-profile actors, in an adventure game setting.

Hell included Dennis Hopper and Grace Jones, and

Ripper featured Christopher Walken, Burgess Meredith, Karen Allen, John Rhys-Davies, and Paul Giamatti among many others.

But he was almost immediately unhappy. “They were a criminal, criminal organization,” he says, referring to Brant’s near prison-sentence over stock manipulation a few years later. “I knew if I stayed there,” he told me, “I would likely end up in jail.” He had harsh words for Brant (who died last year at age 47) in his book:

I now found myself working for a boy–not an immature man or a short guy prone to tantrums, but literally a guy who was barely old enough to drink a beer, a whelp playing office with his trust fund. Worst of all, he was a sinister little manipulator, a true Machiavelli of multimedia . . . As this man-child played business tycoon, I found it impossible to mask my disgust . . . Soon I was living in his doghouse while many others around me were happily residing in his ass [p. 8].

Success has followed most of the Paragon staff. Lennon’s wife, Laura Kampo, left Take Two about the same time he did and became a vice president at Disney Interactive. Mark Seremet stayed at Take two for a few other titles (notably 1998’s Black Dahlia, starring Dennis Hopper and Teri Garr) and then became the COO and CEO of a series of companies, including Zoo Games (2007-2013), indiePub (2013), and Apostrophe Apps (2015-present). Even Antony Davies, who left the company before its first game was released, became a prestigious economist.

|

| F. J. Lennon (from LinkedIn) |

After leaving Take Two, Lennon took at turn towards more children’s-oriented “edutainment.” He wrote Marvel Comics Spider Man: The Sinister Six (1996) and Spider-Man: Venom Factor (1996) for Byron Preiss Multimedia, consulted with Disney Interactive Studios on some interactive storybooks and online games, and consulted on Sesame Street games for Realtime Associates. He calls “the best game I ever worked on” one that was never released: a noir adventure game called To Die For that used the voice and likeness of Humphrey Bogart. Unfortunately, Engineering Animation, Inc. went out of business before the title saw distribution.

In 2009, Lennon wrote an iPhone game called Soul Trapper: Episode 1 – Ollie Ollie Oxen Free! for Realitme Associates–an “audio adventure that draws from the history of radio mystery dramas and the nostalgia of choose-your-own adventure games” (MobyGames). A few years later, Lennon took the main character from the title, Kane Price, and built a novel trilogy around him. Soul Trapper and Devil’s Gate have already been released. Recently, Lennon has been working on educational games for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Although not tied to any specific genre or audience, he has no plans to leave the field any time soon: “One way or another, I’m always going to be in games.”

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/paragon-of-suffering-interview-with-fj.html