From The CRPG Addict

|

| The copyright date on the main screen would seem to refer to the Maces and Magic engine, not to this specific game, which all evidence agrees was released in 1981. |

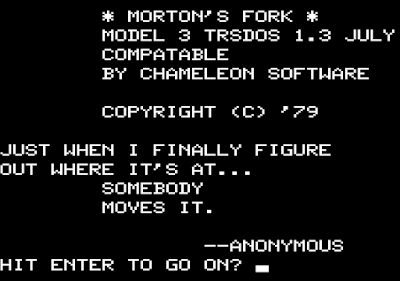

Morton’s Fork

United States

Chameleon Software (developer and original publisher); Adventure International (later publisher)

Chameleon Software (developer and original publisher); Adventure International (later publisher)

Released 1981 for TRS-80 and Apple II

Date Started: 9 January 2020

Date Ended: 9 January 2020

Total Hours: 4

Difficulty: Easy-Moderate (2.5/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at time of posting: (to come later)

Morton’s Fork is the third game in the series generally called Maces & Magic, after Dungeon (1979; later called Balrog or Balrog Sampler) and Stone of Sisyphus (links to my coverage). It’s been difficulty to reconstruct the history of the company even though I spoke to one of its principals, Richard Bumgarner, back in 2013. Chameleon was the moonlighting gig of three Indianapolis-based medical professionals, including x-ray technician Bumgarner. From what I can figure, they conceived of the series in the late 1970s and may have produced and marketed all three games before they struck a publishing deal with Scott Adams’ Adventure International. The first game was originally called Dungeon but later acquired the (nonsensical) Balrog or Balrog Sampler names from AI. Adventure International also seems to be the source of the Maces & Magic series name, although it appears nowhere except on the game packaging. AI also gussied up the title screens a bit, removing the jokes that the creators had placed and (of course) adding the AI name and logo.

|

| A later version of the main screen, from the Apple II edition. |

I’ve spent years trying to find a working version of Morton’s Fork–all three games are notoriously unstable–and the one I was finally able to play lacks the AI logo on the title screen. It’s possible that all three games were produced and marketed as early as 1979 and that the 1981 date is from when they were re-distributed by AI, but so far I haven’t been able to find any magazine evidence of Chameleon selling the second two games directly.

|

| A 1981 ad for the Adventure International releases of the three titles. |

Even if Morton’s Fork had a 1981 release date, its technology is essentially the same as the first game in the series. All three games play exactly the same way, just with different scenarios and puzzles. All three are RPG/text adventure hybrids in which the goal is to collect a fixed number of treasures in a large environment and then find your way out of the game. A mutable hero and wandering monsters are blended with fixed landscapes and unchanging puzzles. The hero could theoretically be swapped between games as if they were “modules” in a traditional RPG experience. The games are thus somewhat like Eamon (1980) but without the central “hub” disk.

|

| A leaflet in the game encourages the player to buy the other games. |

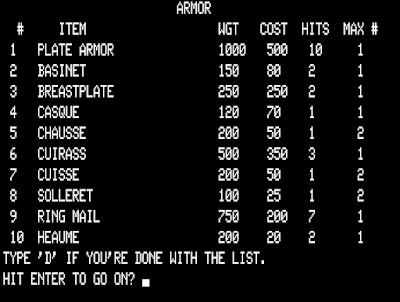

All three start the same way. The player creates a character and the game rolls for strength, luck, dexterity, intelligence, constitution, and charisma. The character is assumed to be a warrior, or a warrior/thief, as there is no magic in the game. After creation, the player is given a chance to purchase weapons and armor from a very long list of obscure terms, apparently created by a doctor who had an encyclopedia or something. You are limited in what you buy by gold and encumbrance.

Dungeon and Stone of Sisyphus had the player explore dungeons with pan-cultural themes, including a hippodrome, an Egyptian room, and an Arabian desert. Fork moves the action to a large castle. The box says that it’s a “wizard’s castle,” but in-game there’s no hint of a wizard. The goal is simply to loot it of as much treasure as possible.

|

| All of the Maces & Magic games feature absurdly detailed weapon and armor lists. |

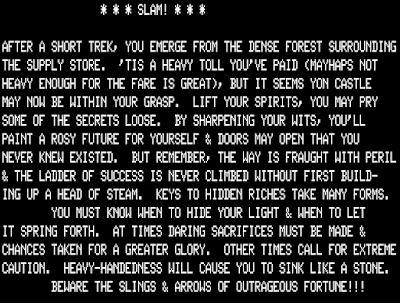

Morton’s Fork begins a bit differently from the other titles by including a “good luck” screen as the game begins. Although it seems full of cliches, it is in fact full of hints. For instance, the advice to “lift your spirits; you may pry some of the secrets loose” is a hint to drink with an NPC in the castle’s cellar. “Keys to hidden riches may take many forms” is a clue to use a hairpin as a lockpick. “You must know when to hide your light and when to let it spring forth” refers to a section of game where you have to light a torch to navigate a dark hallway, but then extinguish it to avoid getting attacked by bats. “Paint a rosy future for yourself and doors may open” is the clue needed for the endgame.

|

| A pre-game text screen full of spoilers. |

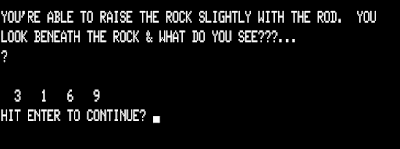

The game eases you into its journey with a long path leading to the castle. You find a token, and then on the next screen a pedestal with a slot. This lowers the drawbridge. You find an iron bar and then a rock with a bunch of scratches; prying the bar reveals a passcode that you must give to the butler when you first arrive. Once you reach the castle’s entry, the game opens up and you can flexibly explore and acquire treasures.

|

| An early puzzle. The number is randomized for each new game. |

The text quality is good, if not as verbose as Infocom games of the period. Inputs are also much more limited. On any given screen, the game gives you numeric inputs for what you can do and where you can go, so you never waste a lot of time typing verbs and nouns that have no effect. The only exception is that on any screen, you can use an item from your inventory, typing a simple (and usually obvious) keyword to specify what you want to do. Thus, you enter a dark room. In addition to following the game’s suggestions to (1) leave or (2) feel your way down the corridor, you can also hit “P” to open your pack, choose the torch, and type LIGHT or IGNITE or any of several synonyms. Most of the game’s puzzles are about using the right inventory item in the right place.

|

| A typical text screen with numbered choices. |

There are fixed combats with certain enemies as well as random combats with guards that roam the corridors. Combat is executed automatically, with your attributes and weapon strengths aggregated into a single combat score and then pitted against your enemy’s. Opponents lose hit points (constitution) each round until one of them dies.

|

| Combat with some castle guards. |

It’s relatively easy to roll a character too weak to win any of the game’s combats, or too poor to afford enough protection to do well. Some of the enemies are, I believe, out of the reach of any first-round character and would have to be fought by a player who escaped a first attempt with a bunch of treasure and used it to buy much better equipment.

The game follows its predecessors by offering a lot of choices but not being necessarily very logical or “fair” in the execution of those choices. For instance, in a den, you’re faced with a fireplace with three levers. One opens a hidden niche and reveals a valuable coin collection. The second causes the fire to roar into the room and kill you. The third releases a “smoke monster” that you have to battle. There really is no way of determining the good from the bad when making your choice.

|

| This is funny, but I’m not sure it’s a logical outcome of taking a glass of punch at a party. |

They aren’t really “role-playing” choices, either. If you find your way into the torture room, you have options to attack the torture troll and thus free his prisoner or help the torture troll crank the wheel that operates the rack. If you attack the troll, you face a near-impossible battle and if you manage to kill him, the prisoner just gruffly wanders away. If you help torture the prisoner, you get valuable intelligence about how to enter the throne room.

Finally, there are an awful lot of instant death situations that are hardly fair. Just wandering into the wrong room can kill you. I suspect these are in place to artificially bolster the game’s replay value. Otherwise, I can’t see how any player would take one month to finish it, which the box says is the average.

|

| All I did was pull on a rope. |

|

| All I did was pull a lever. |

|

| All I did was walk into a room. |

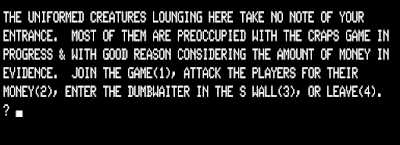

Overall, though, the castle is a fun place to explore. It’s a living place, with guards roaming the halls and shooting craps in their off-duty room, a butler guarding the entryway, and guests dancing the night away in a ballroom. The game isn’t obvious about it, but I suspect your success or failure as you navigate the halls is based partly on your attributes. For instance, if you visit the ballroom you can try to pickpocket the guests. Not only is success based (I suspect) on dexterity, but your ability to even enter and stay in the room has something to do with your charisma.

Your ultimate goal is to assemble a group of treasures. I didn’t find them all, but I found almost all of them:

- A ruby necklace, pickpocketed from the guests in the ballroom.

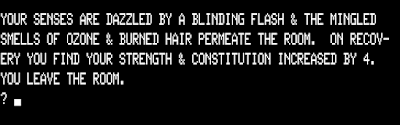

- A large gold figure. It’s found in its “small gold figure” form in a room with piles of objects and a large purple flame. By looking at the objects, you can figure out that throwing items into the flame makes them bigger, so tossing in the “small gold figure” gives you the large one. You also have the option to jump in the flames yourself for a permanent boost to strength and constitution, although you kill yourself if you try it a second time.

|

| The one bit of “character development” in the game. |

- A coin collection, found in a hidden niche in the den’s fireplace.

- A silver tea service, found by picking the lock of a cabinet with a hairpin.

- An emerald orb, found in a dresser that opens when you strike a tuning fork in the room.

- Gold cookies, looted after you kill a “cookie monster” in the pantry off the kitchen. That’s not right.

- A diamond stickpin, simply found in one of the rooms.

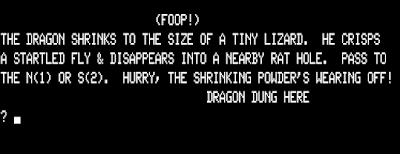

- A multi-jeweled crown, found in the throne room, which you reach after a long sequence of puzzles. You have to walk over a pit and pass a swarm of bats by strategically lighting and extinguishing a torch, pass a large dragon by pouring “shrinking powder” on him, and get by a guard monster by giving him a password that you got by steaming open an envelope.

|

| One of the more memorable sequences in the game, though I never did find any use for the dragon dung. |

- The platinum chameleon, found at the top of a tower that requires a lot of inventory puzzles to successfully climb.

The most difficult puzzle of all is getting out of the castle. I wouldn’t have solved it if I hadn’t figured out that the welcome screen was full of hints. Eventually, you find a couple of rooms that link to a chute. If you climb in the chute, you end up tumbling into a non-descript room with no exits. It’s only from that opening screen that you get the hint to use a bucket of paint (found in a “many-colored room”) to PAINT DOOR on the wall. This causes your door to swing upon and reveal “the corporate headquarters of Chameleon Software,” where “astonished programmers” help you carry your treasures out of the dungeon.

|

| Might and Magic would draw from this ending years later. |

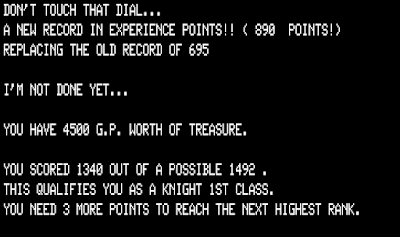

You’re then given your final experience score (from the monsters that you killed) and your final point total from the treasures that you acquired. After a few runs at the game, I was able to achieve 1,340 out of a possible 1,492 points.

|

| I’m going to call this a “win.” |

There were some rooms that I didn’t solve that might have held the additional treasures. There’s a closet off the top of a staircase with a “closet monster” who was always too powerful for me. If you’re unlucky enough to wander your way into the gym, you get picked on by three buff guards. Insulting them causes them to attack you, and I couldn’t defeat them. The other options all lead to negative outcomes. Also, I suspect there was something I was supposed to do with a crystal chandelier.

|

| None of these options leads to anything good. |

Theoretically, you’re supposed to be able to save the character and then re-enter the game, using the riches from your first adventure to purchase better equipment and try again. Unfortunately, for none of the three games have I managed to get a character to survive the transition from game disk to save disk and back again. It’s a miracle when the program runs right at all instead of crashing with vague errors, failing to load the weapon and armor tables, suddenly deciding my character has no inventory, or a host of other problems.

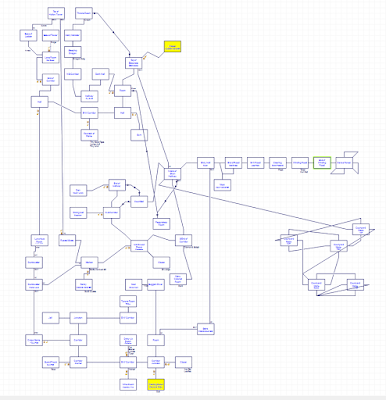

In a GIMLET, Morton’s Fork gets a 17 compared to Dungeon‘s 20. Fork has fewer opportunities for character development, fewer interesting encounters, and a smaller game world than the first game in the series.

|

| My map of the game. |

Before we go, we should discuss the name of the game. A “Morton’s fork” is described by The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms as “a situation in which there are two choices or alternatives whose consequences are equally unpleasant.” It is traced back to John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England under Henry VII. He is said to have argued that a man living ostentatiously could clearly afford higher taxes while a man living frugally must be saving his money–and could thus afford higher taxes. The “water test” for witches (if you float, you’re a witch and you’re executed; if you sink and drown, you’re innocent) is often given as an example of a Morton’s Fork.

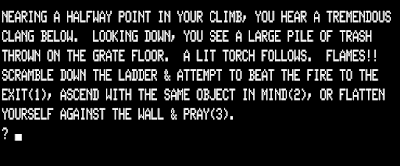

|

| An in-game Morton’s fork. You die in a fire no matter what option you choose. |

It’s a curious title for a game, particularly since the only “fork” in the game is a tuning fork, and it’s hardly a centerpiece. But like Stone of Sisyphus, which references a process of doing the same thankless task repeatedly, I think the creators were making a commentary on adventure games and perhaps even “choose your own adventure”-style books, in which multiple options lead to the same outcome. There’s one notable moment in the game in which you’re given three ways to escape from a fire, and none of them work.

Were they critiquing themselves? Making fun of their own players, who paid $29.95 for the game only to presumably lose three consecutive characters to the same fire? We can’t say. All we know is that the creators chose a title that ostensibly pokes fun at the laziest of adventure game tropes–and then they stocked the game with actual examples.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/game-351-mortons-fork-1981.html