From The CRPG Addict

|

| As an expansion of Hellfire Warrior, the game has no main title screen. |

Ranking at Time of Posting: (to come later)

|

| A typical Acheron screen has me fighting a fungusman in a twisty cavern. A treasure can be seen beyond him. |

|

| Kronus himself appears randomly throughout the game’s levels and cannot be killed. |

|

| My character at the beginning of this session. I created him as a veteran of Hellfire Warrior. |

|

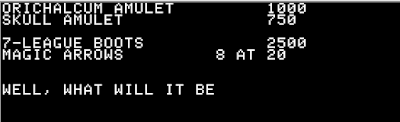

| Available magic items. |

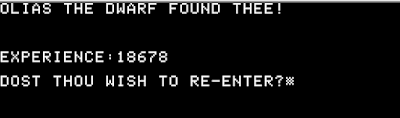

In one last screen before you enter, you can donate money to Benedic the Cleric’s mission, which seems to increase the chance that Benedic is the one that finds and resurrects you when you die. Otherwise, you may be found by Lowenthal the Wizard, who takes all magic items that you own before returning you to the town for resurrection; or Olias the Dwarf, who takes all your items; or a random monster, who just eats you.

|

| I confess I reloaded save states in such circumstances. |

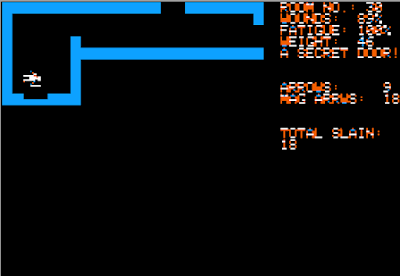

Once inside the dungeon, the game behaves just like the earlier incarnations. You use “R,” “L,” and “V” to turn and rotate the character and then type a number from 1 to 9 indicating how many steps to move in your facing direction. “S” searches for traps, “E” searches for secret doors (you have to be pretty close to the door), and “O” opens them.

|

| Finding a secret door. |

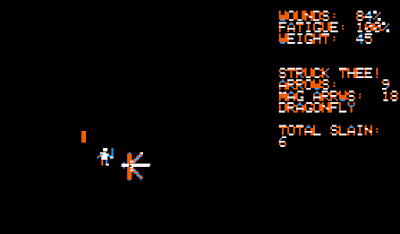

When monsters appear, you can try to shoot them at a distance with a regular arrow (“F”) or a magic arrow (“M”), or wait until they get close and use “A,” “T,” and “P” for attack, thrust, and parry. When the monsters get your hit points down, you can heal with a salve (“H”), nectar (“N”), or elixir (“Y”) if you’ve purchased them. If the room has a treasure, you grab it with “G.” The controls are all quite intuitive except for movement, which never stops being clunky.

|

| Melee combat with a grifffin. There are, alas, no spells in the game. |

You have to be careful about stamina. The game tracks encumbrance (including weapons, armor, and found treasures), and the faster you move with more weight, the faster your stamina depletes. Standing still causes it to (slowly) recharge, and you don’t want to be caught in combat in such situations. I had fewer problems with it here than in the original Hellfire Warrior.

The rooms and corridors are all uniformly dull–the top-down equivalent of Wizardry‘s wireframes from the same year. (There are mild icon animations but nothing to get excited about.) This is where the Dunjonquest series is greatly enhanced by the monster, trap, room, and treasure descriptions in the accompanying manual. On the screen, you may enter Room 16, but with the manual, you know you’ve entered a cave where:

The air is intolerably hot. To the west you can see roaring flames. As you make your way through the passage, you stumble over something. Looking down, you see the fragments of a huge egg. It would seem that the Dragon has borne young ones.

If you meet one of the baby dragons, you consult the manual to see that:

Although this creature resembles its parent closely in its scaled, wormlike form, it is fortunately much smaller, typically 6-8 feet in length. Even though the immature beast cannot breathe flame (and luckily so!), it will attack anything it meets with ferocity.

You defeat him and head down the corridor, only to accidentally stumble in a dragonfire trap! The manual has you covered there, too:

With a titanic roar, the corridor fills with the burning flame of the Dragon’s breath. You should have been quieter, more careful. Now it knows you are here.

But eventually you defeat your foes and pick up the treasure in the room. The screen tells you that you’ve acquired Treasure #8:

A quaint piece of giantish artwork, a skull carved from a huge agate. Surely some collector of such things would buy it, but for how much?

As noted, levels 2 and 4 don’t have any room descriptions–some limitation imposed by the game basically faking the Hellfire Warrior application into thinking it’s playing Hellfire Warrior levels. But to compensate, Reiche used treasure descriptions more as encounter flags rather than literal treasures. Sometimes, you find healing items that can be repeatedly taken. Other times, you find a clue, as in “a severed hand . . . clutching spasmodically” that eventually “points north, up the corridor.” And still other times, it’s just flavor text, as in “the floating remains of one of the kraken’s more recent meals.”

The overall dungeon designs are superior to the earlier games in the series. You start in the “Abode of the Dragon,” a classic dungeon of rooms and passages featuring trolls, ogres, giants, grues, and the titular dragon. These are not Level 1 monsters, so you’re expected to bring an experienced character. The room descriptions have you begin in a field and (depending on the way you go) either enter a tunnel immediately or follow a shoreline around to a cave entrance. They both converge on the dragon’s lair, one via a straight path through monsters and treasures and the other taking a shortcut through a secret door. A side area leads to a unicorn’s grove, where a non-hostile unicorn lets you take an opal necklace. Other treasures found throughout the area include a magic sword and a healing potion; I think this is the first Dunjonquest game where any of the found treasures can remain a permanent part of your character.

|

| The game’s take on a “grue.” |

The demon Kronus occasionally pops up in all of the levels, and there’s nothing to do but run away. The manual says that he cannot be killed, and my experience bears that out.

The first Key of Acheron, a “spherical ruby gem as large as your fist,” is found beyond the slain dragon. Overall, the level has more valuable treasures than the others, and if you thoroughly explore, by the time you return to the surface, you’ll have enough money to enchant your sword and armor and drink every elixir in the apothecary’s shop before your next trip.

|

| The first key lies beyond the dragon. |

“The Temple in the Jungle” offers no room descriptions and simply has you navigating a fairly open level with different types of dinosaurs, giant dragonflies, and Sserpa (snake god) shamans. For the first time in the series, this level has an adventure game-like quality where the “rooms” don’t lie in consistent directions, and the map warps on itself. You have to create a little node map to find your way through. You eventually find the “amethyst key” in a room occupied by a giant tarantula.

|

| Fighting a giant dragonfly in what we have to imagine is a trackless jungle. |

“The Crystal Caves” puts you in an extinct volcano. There are some interesting “trap” areas that the game suggests are deep pools full of piranhas from which you have to climb your way out. Mechanically, you do this by searching for secret doors, but a player with an imagination will appreciate the game’s attempts to do something clever with limited mechanics.

Battling lava beasts, lizards, fungus men, salt slimes and dodging earthquakes and cave-ins (again, all described in detail in the manual), you eventually find your way through secret doors and recover the “emerald key” in a cavern.

|

| I collect the third gem. |

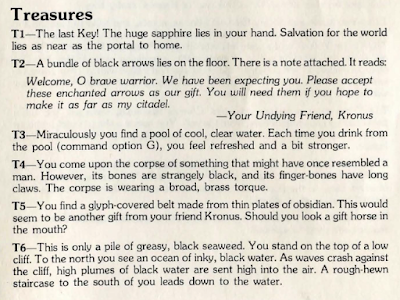

The last level is called “The Shadowland of Kronus.” Like the jungle, it lacks room descriptions, but here almost none of the treasures are actually treasures. Instead, they generally contain clues or taunts from Kronus.

|

| Some of the treasure descriptions from the final level. |

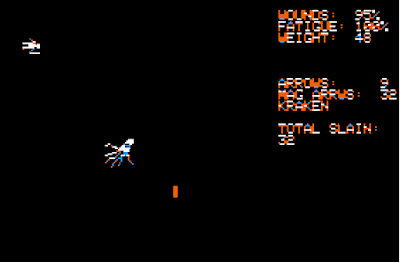

The level takes the longest to explore. Eventually, you find your way through a secret door to a large, open water area, where the game uses a treasure encounter to suggest you’re paddling around on a boat. Waves and “black rain” do damage to the character while you’re attacked by shadow bats, fiends, and krakens. Another node map is necessary to chart a path through the area.

|

| Release the kraken! |

You arrive ultimately on the shores of a citadel (this is all related via treasure paragraphs) and a walkway where numerous gaps suggest a “broken railing”; going through these gaps leads to instant death. Eventually, you come to Kronus’s chambers with side-rooms for a torture chamber, library, and bedroom. Each room has appropriate monsters, like wraiths, astral skulls, and automatons. I particularly enjoyed the treasure encounter in the library, with its Lovecraftian allusions:

You stand in a library filled with books, scrolls, and tablets of arcane and eldritch knowledge. Looking around, you find such titles as De Mysteriis Vermis, The King in Yellow, and a complete edition of the Pnatonik Manuscripts. Resting on a nearby table you find a particularly interesting volume entitled The Necronomicon. When you open the book you find it filled with incomprehensible writings, and you feel an unholy chill pass through your body. Perhaps some wizard will buy this strange librum.

A secret door leads from Kronus’s chambers to the final area. You pass through a room of fake sapphire keys (and lots of monsters) before arriving in a room with Kronus himself guarding the real final key. As before, there’s no point in fighting Kronus. You have to dart up, grab the key, find a secret door in the north wall, and escape the dungeon before he kills you.

|

| The final encounter. |

|

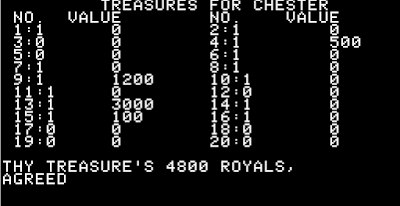

| The appearance of Treasure #1 four times in a row (this is the last) is the only “proof” that I’ve won. |

****

I’d like to ask a favor of my U.S. readers. I’m looking for places across the United States that sell Diet Coke with Ginger Lime in 20-ounce bottles. Exactly that–no other flavors, please, and no cans. Just Diet Coke with Ginger Lime in 20-ounce bottles. If you happen to see them at a local convenience store, drug store, or whatever, I would appreciate an e-mail to crpgaddict@gmail.com. Thank you!

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/04/game-324-keys-of-acheron-1981.html