The beginning of serious work on the operating system that would come to be known as OS/2 left Microsoft’s team of Windows developers on decidedly uncertain ground. As OS/2 ramped up, Windows ramped down in proportion, until by the middle of 1986 Tandy Trower had just a few programmers remaining on his team. What had once been Microsoft’s highest-priority project had now become a backwater. Many were asking what the point of Windows was in light of OS/2 and its new GUI, the Presentation Manager. Steve Ballmer, ironically the very same fellow who had played the role of Windows’s cheerleader-in-chief during 1984 and 1985, was now the most prominent of those voices inside Microsoft who couldn’t understand why Trower’s team continued to exist at all.

Windows survived only thanks to the deep-seated instinct of Bill Gates to never put all his eggs in one basket. Stewart Alsop II, editor-in-chief of InfoWorld magazine during this period:

I know from conversations with people at Microsoft in environments where they didn’t have to bullshit me that they almost killed Windows. It came down to Ballmer and Gates having it out. Ballmer wanted to kill Windows. Gates prevented him from doing it. Gates viewed it as a defensive strategy. Just look at Gates. Every time he does something, he tries to cover his bet. He tries to have more than one thing going at once. He didn’t want to commit everything to OS/2, just on the off chance it didn’t work. And in hindsight, he was right.

Gates’s determination to always have a backup plan showed its value around the beginning of 1987, when IBM informed Microsoft of their marketing plans for their new PS/2 hardware line as well as OS/2. Gates had, for very good reason, serious reservations about virtually every aspect of the plans which IBM now laid out for him, from the fortress of patents being constructed around the proprietary Micro Channel Architecture of the PS/2 hardware to an attitude toward the OS/2 software which seemed to assume that the new operating system would automatically supersede MS-DOS, just because of the IBM name. (How well had that worked out for TopView?) “About this time is when Microsoft really started to get hacked at IBM,” remembers Mark Mackaman, Microsoft’s OS/2 product manager at the time. IBM’s latest misguided plans, the cherry on top of all of Gates’s frustration with his inefficient and bureaucratic partners, finally became too much for him. Beginning to feel a strong premonition that the OS/2 train was going to run off the tracks alongside PS/2, he suddenly started to put some distance between IBM’s plans and Microsoft’s. After having all but ignored Windows for the past year, he started to talk about it in public again. And Tandy Trower found his tiny team’s star rising once again inside Microsoft, even as OS/2’s fell.

The first undeniable sign that a Windows rehabilitation had begun came in March of 1987, when Microsoft announced that they had sold 500,000 copies of the operating environment since its release in November of 1985. This number came as quite a surprise to technology journalists, whose own best guess would have pegged Windows’s sales at 10 percent of that figure at best. It soon emerged that Microsoft was counting all sorts of freebies and bundle deals as regular unit sales, and that even by their own most optimistic estimates no more than 100,000 copies of Windows had ever actually been installed. But no matter. For dedicated Microsoft watchers, their fanciful press release was most significant not for the numbers it trumpeted but as a sign that Windows was on again.

According to Paul and George Grayson, whose company Micrografix was among the few which embraced Windows 1, the public announcement of OS/2 and its Presentation Manager in April of 1987 actually lent Microsoft’s older GUI new momentum:

Everybody predicted when IBM announced OS/2 and PM [that] it was death for Windows developers. It was the exact opposite: sales doubled the next month. Everybody all of a sudden knew that graphical user interfaces were critical to the future of the PC, and they said, “How can I get one?”

You had better graphics, you had faster computers, you had kind of the acknowledgement that graphical user interfaces were in your future, you had the Macintosh being very successful. So you had this thing, this phenomenon called Mac envy, beginning to occur where people had PCs and they’d look at their DOS-based programs and say, “Boy, did I get ripped off.” And mice were becoming popular. People wanted a way to use mice. All these things just kind of happened at one moment in time, and it was like hitting the accelerator.

It did indeed seem that Opportunity was starting to knock — if Microsoft could deliver a version of Windows that was more compelling than the first. And Opportunity, of course, was one house guest whom Bill Gates seldom rejected. On October 6, 1987, Microsoft announced that Windows 2 would ship in not one but three forms within the next month or two. Vanilla Windows 2.03 would run on the same hardware as the previous version, while Windows/386 would be a special supercharged version made just for the 80386 CPU — a raised middle finger to IBM for refusing to let Microsoft make OS/2 an 80386-exclusive operating system.

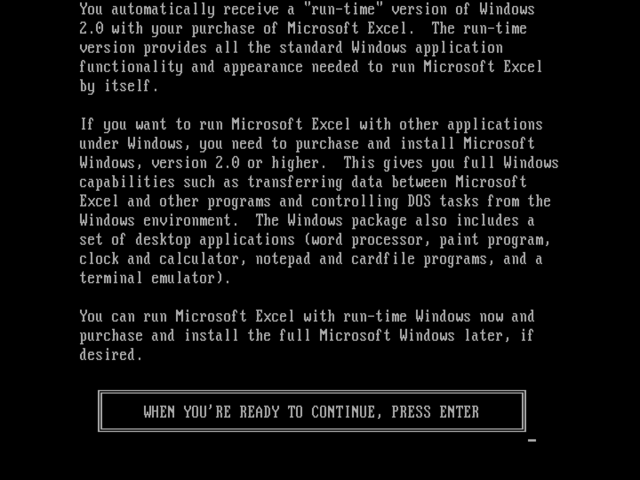

But the most surprising new Windows product of all actually bore the name “Microsoft Excel” on the box. After struggling fruitlessly for the past two years to get people to write native applications for Windows, Microsoft had decided to flip that script by making a version of Windows that ran as part of an application. The new Excel spreadsheet would ship with what Microsoft called a “run-time” version of Windows 2, sufficient to run Excel and only Excel. When people tried Excel and liked it, they’d go out and buy a proper Windows in order to make all their computing work this way. That, anyway, was the theory.

Whether considered as Excel for Windows or Windows for Excel, Microsoft’s latest attempt to field a competitor to Lotus 1-2-3 already had an interesting history. It was in fact a latecomer to the world of MS-DOS, a port of a Macintosh product that had been very successful over the past two years.

After releasing a fairly workmanlike version of Multiplan for the Macintosh back in 1984, Microsoft had turned their attention to a more ambitious Mac spreadsheet that would be designed from scratch in order to take better advantage of the GUI. The wisdom of committing resources to such a move sparked considerable debate both inside and outside their offices, especially after Lotus announced plans of their own for a Macintosh product called Jazz.

Lotus 1-2-3 on MS-DOS was well on its way to becoming the most successful business application of the 1980s by combining a spreadsheet, a database, and a business-graphics application in one package. Now, Lotus Jazz proposed to add a word processor and telecommunications software to that collection on the Macintosh. Few gave Microsoft’s Excel much chance on the Mac against Lotus, the darling of the Fortune magazine set, a company which could seemingly do no wrong, a company which was arguably better known than Microsoft at the time and certainly more profitable. But when Jazz shipped on May 27, 1985, it was greeted with unexpectedly lukewarm reviews. It felt slow and painfully bloated, with an interface that felt more like a Baroque fugue than smooth jazz. For the first time since toppling VisiCalc from its throne as the queen of American business software, Lotus had left the competition an opening.

Excel for Mac shipped on September 30, 1985. In addition to feeling elegant, fast, and easy in contrast to the Lotus monstrosity, Microsoft’s latest spreadsheet was also much cheaper. It outdistanced its more heralded competitor in remarkably short order, quickly growing into a whale in the relatively small pond that was the Macintosh business-applications market. In December of 1985, Excel alone accounted for 36 percent of said market, compared to 9 percent for Jazz. By the beginning of 1987, 160,000 copies of Excel had been sold, compared to 10,000 copies of Jazz. And by the end of that same year, 255,000 copies of Excel had been sold — approximately one copy for every five Macs in active use.

Such numbers weren’t huge when set next to the cash cow that was MS-DOS, but Excel for the Macintosh was nevertheless a breakthrough product for Microsoft. Prior to it, system software had been their one and only forte; despite lots and lots of trying, their applications had always been to one degree or another also-rans, chasing but never catching market leaders like Lotus, VisiCorp, and WordPerfect. But the virgin territory of the Macintosh — ironically, the one business computer for which Microsoft didn’t make the system software — had changed all that. Microsoft’s programmers did a much better job of embracing the GUI paradigm than did their counterparts at companies like Lotus, resulting in software that truly felt like it was designed for the Macintosh from the start rather than ported over from another, more old-fashioned platform. Through not only Excel but also a Mac version of their Word word processor, Microsoft came to play a dominant role in the Mac applications market, with both products ranking among the top five best-selling Mac business applications more months than not during the latter 1980s. Now the challenge was to translate that success in the small export market that was the Macintosh to Microsoft’s sprawling home country, the land of MS-DOS.

On August 16, 1987, Microsoft received some encouraging news just as they were about to take up that challenge in earnest. For the first time ever, their total sales over the previous year amounted to enough to make them the biggest software company in the world, a title which they inherited from none other than Lotus, who had enjoyed it since 1984. The internal memo which Bill Gates wrote in response says everything about his future priorities. “[Lotus’s] big distinction of being the largest is being taken away,” he said, “before we have even begun to really compete with them.” The long-awaited version of Excel for PC compatibles would be launched with two important agendas in mind: to hit Lotus where it hurt, and to get Windows 2 — some form of Windows 2 — onto people’s computers.

Excel for Windows — or should we say Windows for Excel? — reached stores by the beginning of November 1987, to a press reception that verged on ecstatic. PC Magazine‘s review was typical:

Microsoft Excel, the new spreadsheet from Microsoft Corp., could be one of those milestone programs that change the way we use computers. Not only does Excel have a real chance of giving 1-2-3 its most serious competition since Lotus Development Corp. introduced that program in 1982, it could finally give the graphics interface a respectable home in the starched-shirt world of DOS.

For people who cut their teeth on 1-2-3 and have never played with a Mac, Excel looks more like a video game than a serious spreadsheet. It comes with a run-time version of Microsoft Windows, so it has cheery colors, scroll bars, icons, and menu bars. But users will soon discover the beauty of Windows. Since it treats the whole screen as graphics, you can have different spreadsheets and charts in different parts of the screen and you can change nearly everything about the way anything looks.

Excel won PC Magazine‘s award for “technical excellence” in 1987 — a year that notably included OS/2 among the field of competitors. The only thing to complain about was performance: like Windows itself, Excel ran like a dog on an 8088-based machine and sluggishly even on an 80286, requiring an 80386 to really unleash its potential.

Especially given the much greater demands Excel placed on its hardware, it would have to struggle long and hard to displace the well-entrenched Lotus 1-2-3, but it would manage to capture 12 percent of the MS-DOS spreadsheet market in its first year alone. In the process, the genius move of packaging Windows itself with by far the most exciting Windows application yet created finally caused significant numbers of people to actually start using Microsoft’s GUI, paving the road to its acceptance among even the most conservative of corporate users. Articles by starch-shirted Luddites asking what GUIs were really good for became noticeably less common in the wake of Excel, a product which answered that question pretty darn comprehensively.

Of course, Excel could never have enjoyed such success as the front edge of Microsoft’s GUI wedge had the version of Windows under which it ran not been much more impressive than the first one. Ironically, many of the most welcome improvements came courtesy of the people from the erstwhile Dynamical Systems Research, the company Microsoft had bought, at IBM’s behest, for their work on a TopView clone that could be incorporated into OS/2. After IBM gave up on that idea, most of the Dynamical folks wound up on the Windows team, where they did stellar work. Indeed, one of them, Nathan Myhrvold, would go on to became Microsoft’s chief software architect and still later head of research, more than justifying his little company’s $1.5 million purchase price all by himself. Take that, IBM!

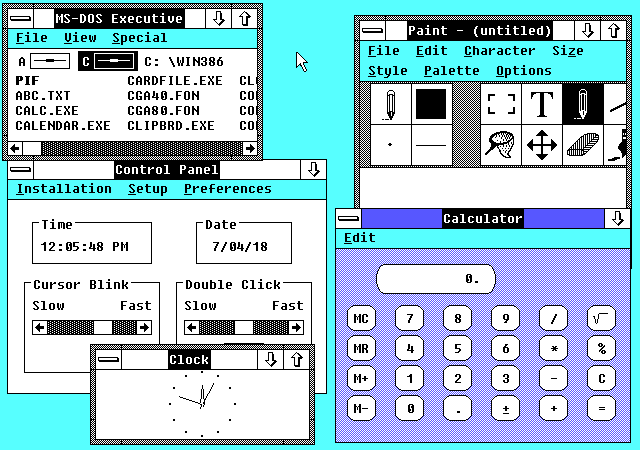

From the user’s perspective, the most plainly obvious improvement in Windows 2 was the abandonment of Scott MacGregor’s pedantic old tiled-windows system and the embrace of a system of sizable, draggable, overlappable windows like those found on the Macintosh. For the gearheads, though, the real excitement lay in the improvements hidden under the hood of Windows/386, which made heavy use of the 80386’s “virtual” mode. Windows itself and its MS-DOS plumbing ran in one virtual machine, and each vanilla MS-DOS application the user spawned therefrom got another virtual machine of its own. This meant that as many MS-DOS applications and native Windows applications as one wished could now be run in parallel, under a multitasking model that was preemptive for the former and cooperative for the latter. The 640 K barrier still applied to each of the virtual machines and was thus still a headache, requiring the usual inefficient workarounds in the form of extended or expanded memory for applications that absolutely, positively had to have access to more memory. Still, having multiple 640 K virtual machines at one’s disposal was better than having just one.

Windows/386 was arguably the first version of Windows that wasn’t more trouble than it was worth for most users. If you had the hardware to run it, it was a very compelling product, even if the realities of the software market meant that you used it more frequently to multitask old-school MS-DOS applications than to run native Windows applications.

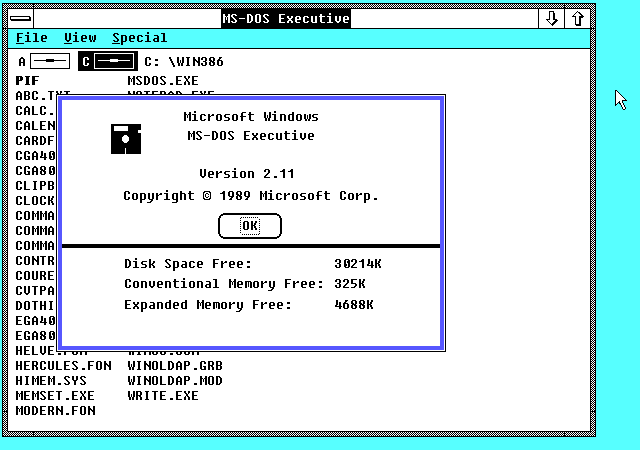

Microsoft themselves didn’t seem to entirely understand the relationship between Windows and OS/2’s Presentation Manager during the late 1980s. This version of Windows inexplicably has the “Presentation Manager” name as well on some of the disks. No wonder users were often confused as to which product was the real Microsoft GUI of the future. (Version 2.11 of Windows/386, the one we’re looking at here, was released some eighteen months after the initial 2.01 release, which I couldn’t ever manage to get running under emulation due to strange hard-drive errors. But the material differences between the two versions are relatively minor.)

Windows 2 remains less advanced than Presentation Manager in many ways, such as the ongoing lack of any concept of application installation. Without it, we’re still left to root around through the individual files on the hard disk in order to start applications.

Especially in the Windows/386 version, most of the really major improvement that came with Windows 2 are architectural enhancements that are hidden under the hood. There is, however, one glaring exception to that rule: the tiled windows are gone, replaced with a windowing system that works the way we still expect such things to work today. You can drag these windows, you can size them, and you can overlap them as you will.

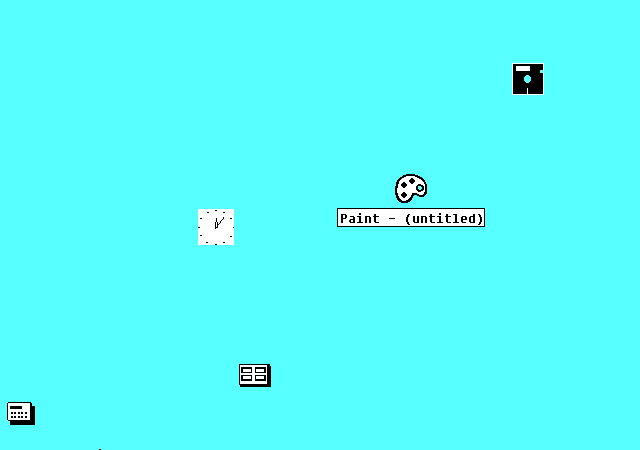

The desktop concept is still lacking, but we’re making progress. Like in Windows 1, icons on the desktop only represent running applications that have been minimized. Unlike in Windows 1, these icons can now be dragged anywhere on the proto-desktop. From here, it would require only one more leap of logic to start using the icons to represent things other than running applications. Baby steps… baby steps.

Windows/386 removes some if by no means all of the sting from the 640 K barrier. Thanks to the 80386’s virtual mode, vanilla MS-DOS applications can now run in memory above the 640 K barrier, leaving the first 640 K free for Windows itself and native Windows applications. So few compelling examples of the latter existed during Windows/386’s heyday that the average user was likely to spend a lot more time running MS-DOS applications with it anyway. In this scenario, memory was ironically much less of problem than it would have been had the user attempted to run many native applications.

One of the less heralded of Microsoft’s genius marketing moves has been the use of Microsoft Excel as a sort of Trojan horse to get people using Windows. When installed on a machine without Windows, Excel also installs a “run-time” version of the operating environment sufficient only to run itself. Excel would, as Microsoft’s thinking went, get people used to a GUI and get them asking why they couldn’t use one for the other tasks they had to accomplish on the computer. “Why, as a matter of fact you can,” would go Microsoft’s answer. “You just need to buy this product called Windows.” Uptake wouldn’t be instant, but Excel did become quite successful as a standalone product, and did indeed do much to pave the way for the eventual near-universal acceptance of Windows 3.

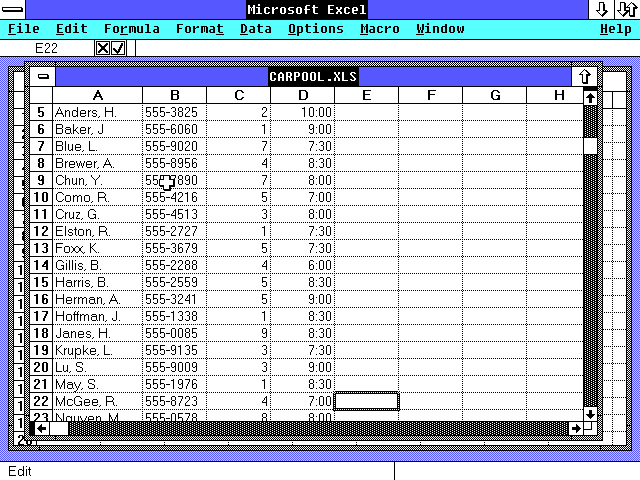

Excel running under either a complete or a run-time version of Windows. When it appeared alongside Windows 2 in late 1987, it was by far the most sophisticated and compelling application yet made for the environment, giving the MS-DOS-using masses for the first time a proof of concept of what a GUI could mean in the real world.

Greatly improved though it was, Windows 2 didn’t blow the market away. Plenty of the same old problems remained, beginning and for many ending with the fact that seeing it at its best required a pricey 80386-based computer. In light of this, third-party software developers didn’t exactly stampede onto the Windows bandwagon. Still, having been provided with such a wonderful example in the form of Microsoft Excel of how compelling (and profitable) a Windows application done right could be, some of them did begin to commit some resources to Windows as well as vanilla MS-DOS. Throughout the life of Windows 2, Microsoft made a standard practice of giving their run-time version of it to outside application developers as well as their own, all in a bid to give people a taste of a GUI through the word processor, spreadsheet, or paint program they were going to buy anyway. To some extent at least, it worked. Some users turned that taste into a meal by buying boxed copies of Windows 2, and still more were intrigued enough to quit scoffing and start accepting that GUIs in general might truly be a better way to get their work done — if not now, then at some point in the future, when the hardware and the software had both gotten a little bit better.

By the spring of 1988, Windows was still at least an order of magnitude away from meeting the goal Bill Gates had once stated it would manage before the end of 1984: that of being installed on 90 percent of all MS-DOS computers. But, even if Windows 2 hadn’t blown anyone away, it was doing considerably better than Windows 1, and certainly seemed to have more momentum than OS/2’s as-yet-unreleased Presentation Manager. Granted, neither of these were terribly high bars to clear — and yet there was a dawning sense that Windows, six and a half years on from its birth as the humble Interface Manager, might just get the last laugh on the MS-DOS command line after all. Microsoft was already formulating plans for a Windows 3, which was coming to be seen both inside and outside the company as the pivotal version, the point where steadily improving hardware would combine with better software to break the GUI into the business-computing mainstream at long last. No, it wasn’t 1984 any more, but better late than never.

And then a new development threatened to pull the rug out from under all the progress that had been made. On March 17, 1988, Apple blindsided Microsoft by filing a lawsuit against them in federal court, alleging that the latter had stolen the former’s intellectual property by copying the “look and feel” of the Macintosh GUI. With the gauntlet thus thrown down, the stage was set for one of the most titanic legal battles in the history of the computer industry, one with the potential to fundamentally alter the very nature of the software business. At stake as well was the very existence of Windows just as it finally seemed to be getting somewhere. And as went Windows, Bill Gates was coming to believe once again, so went Microsoft. In order for both to survive, he would now have to win a two-front war: one in the marketplace, the other in the court system.

(Sources: the books The Making of Microsoft: How Bill Gates and His Team Created the World’s Most Successful Software Company by Daniel Ichbiah and Susan L. Knepper, Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire by James Wallace and Jim Erickson, Gates: How Microsoft’s Mogul Reinvented an Industry and Made Himself the Richest Man in America by Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, Computer Wars: The Fall of IBM and the Future of Global Technology by Charles H. Ferguson and Charles R. Morris, and Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World’s Most Colorful Company by Owen W. Linzmayer; PC Magazine of November 10 1987, November 24 1987, December 22 1987, April 12 1988, and September 12 1989; Byte of May 1988 and July 1988; Tandy Trower’s “The Secret Origins of Windows” on the Technologizer website. Finally, I owe a lot to Nathan Lineback for the histories, insights, comparisons, and images found at his wonderful online “GUI Gallery.”)

Original URL: https://www.filfre.net/2018/07/doing-windows-part-5-a-second-try/