From The CRPG Addict

|

The party continues to explore The Seventh Link‘s large world.

|

This entry posits a thesis that I’ve never explicitly articulated before and probably haven’t spent enough time thinking about its flaws. I thus particularly invite you to join me in the comments and add or modify the thesis’s tenets. It doesn’t feel to me like a particularly original argument, so I’d also be glad for any references to other writers who have argued something similar.

The thesis is that a perfect game (although this might apply to films and novels, too) is something like a cube–equal and balanced on three dimensions. I am calling those dimensions

breadth,

depth, and

immersion.

|

| Fate: Gates of Dawn (1991) had an enormous game world and not enough happening within it. |

Breadth refers primarily to the physical size of the game. It can be measured in dungeon squares or tiles, or in modern games the length of time it takes to travel from one end to the other. It also refers to the length of time it takes to play and win the game; while this is often a function of size, it can also be manipulated to make a small game seem larger or a large game seem smaller; for instance, in the use of fast travel (making a large game seem smaller) or the re-use of maps (making a small game seem larger).

Depth refers to the things that you find and to the things that happen within that game world. The specific elements depend on the game’s genre, but for RPGs it includes things like the backstory, lore, NPCs, quests, and character development.

|

Two separate multi-volume book series covering the biography of a single NPC might be too much for some games–but not for The Elder Scrolls’ huge game world.

|

We’ll get to immersion in a minute, but for now let’s pretend that my thesis has only these two elements, and I’m arguing that a good game is like a square: you want a breadth equal to its depth and vice versa. The easiest way to engage the thesis is to imagine the extremes. A game with extreme breadth and almost no depth would be something like Red Dead Redemption 2 or Fallout 4 if all you could do was explore the map. You’d get bored pretty fast.

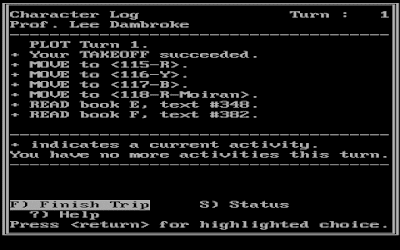

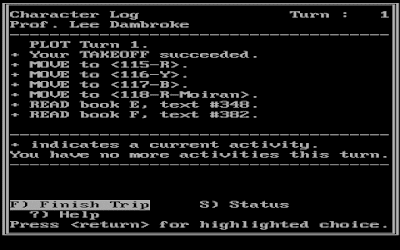

The opposite–a game with extreme depth and no breadth–is harder to envision because it almost wouldn’t be a computer game at all. Imagine a game of only a couple of dozen squares in which every time your character moves, you have to read paragraph after paragraph of text and engage in hours-long dialogues with multiple NPCs. The computer part would feel superfluous. The

Star Saga games are the closest I can imagine in real life.

|

| Star Saga (1987) mostly used the computer application to direct “players” to chapters in a several hundred-page book. |

My thesis is that a good game doesn’t have to feature a lot of breadth or depth, but rather than it needs to keep them in balance. It is thus not absurd to argue that Ultima IV is a better game than Dragon Age: Inquisition just even though the latter is bigger and has far more story and lore. The issue isn’t which has more but which does a better job balancing the two. Ultima IV has just enough backstory and in-game dialogue, lore, and other content to support the size of Britannia and the length of the game. If had featured 200 books with as much text as those found in The Elder Scrolls, it would have gone too far. It would also have gone too far it if had featured the same content as it does, but in a world four times the size.

I have seen the phrase “wide as an ocean, deep as a puddle” applied numerous times to

Skyrim. I find it unfair, but only a little. I’d say that it’s as wide as the Pacific Ocean but deep as the Arctic Ocean. The game has plenty of depth. It would be insane to argue that it has less depth (e.g., less content, less meaningful NPC interaction, fewer choices, less role-playing) than fan favorites like

Dungeon Master, any of the

Ultima titles, or even

Planescape: Torment. But people aren’t objecting to its

absolute depth; they’re objecting to its depth relative to its breadth. When I say a game is “too long” in my GIMLET, I’m not saying that crossed some objective threshold so much as I’m saying that it’s too long for its content.

|

| Ultima Underworld (1992), through a combination of graphics, sound, and interface, is one of the first games to make you feel truly “immersed” in the setting. |

Let’s talk about the third axis. I debated for a while about including it, but I do think it’s important. Immersion deals with the game’s capacity to make you feel like you are truly “occupying” its world, and it’s primarily a function of graphics and sound–although we must allow for skilled developers who can engage the player’s imagination in the absence of these things, as a good author does.

To understand the importance of this axis, imagine a large game that you believe balances breadth and depth well. Fallout: New Vegas seems to be a fan favorite. Now imagine that it has no sound and the wireframe graphics of Wizardry. Is it still on your top 10 list? No matter how well a game balances size and content, there’s a point at which it becomes “too much” if it can’t fully engage your senses and immerse you in its world.

None of these variables is completely objective, and immersion is probably the least objective of the three. Its importance has a lot to do with your age and experience level with older games. I still think the graphics in

Morrowind are beautiful, but last week, I stumbled on a Reddit thread in which someone posted an image of a horse falling over in

Red Dead Redemption 2 and leaving a horse-sized imprint in the mud, and half the commenters were complaining that the imprint wasn’t realistic enough. Even among those of us with a high tolerance for primitive graphics, immersion is a mutable characteristic. A game that seems like a solid cube today will slowly flatten as we become used to better graphics and sound.

|

Watching the sunset in Morrowind (2003) still seems lovely to me, but to some people these graphics are hopelessly outdated.

|

The greatest developmental sins are committed by RPG authors who fail to consider these elements of balance. Take Fate: Gates of Dawn, which took me 272 hours to win and featured both an enormous outdoor game world as well as enormous, multi-leveled dungeons. It was a game of ridiculous breadth, and while it had a certain amount of depth–perhaps even more than the typical RPG of the time–it didn’t have enough depth to equal the breadth. I still recommend that modern players limit themselves to the opening area and the Cavetrain quest, as those first 50 hours let you experience everything good about the game; the remaining 5/6 of its length is utterly superfluous. Knights of Legend, Wizardry V, and all three Bard’s Tale games are all good examples of games whose size greatly exceed the amount of interesting content they provide.

It’s tough to find reverse examples–too much depth and not enough breadth. I mentioned the

Star Saga games earlier, in which you make a move in a computer application and then read pages of text in an accompanying book. I ended up rejecting them not because they weren’t RPGs because they weren’t really

computer games. There are other examples of games that wanted to do something epic with their themes but struggled with an interface that could support their intentions.

ICON: Quest for the Ring is a good example. The three Richard Seaborne games–particularly

Escape from Hell and

The Tower of Myraglen–had deep philosophical ambitions that weren’t quite matched by the gameplay experience.

|

The Tower of Myraglen (1987) wanted to be more profound than the breadth of the game could really support.

|

But even games near-perfectly balanced in depth and breadth often suffer when we consider the immersion axis. I will grant you that there’s a somewhat high threshold before it becomes important. It arguably never becomes important in simple arcade games, and even with RPGs, anyone who argues that Wizardry or Ultima or Dungeons of Daggorath are bad games because of their graphics is expressing an opinion so out-of-touch with my own values that I’d almost regard it as a character flaw. But even I would argue there’s no place for a soundless wireframe game that takes 200 hours. There is a degree to which good descriptive text can substitute for graphics, which is why I often praise games for including it, but even I would probably balk at an all-text Fallout 4.

Deathlord is a good example of a game that’s reasonably square with breadth and depth but still largely fails because it’s just too big for an iconographic game. I think we’re going to start to see this a lot more with 1990s titles, as the use of hard disk installations allows for physically enormous games that are still a bore to explore. The first Elder Scrolls title, Arena, will probably be an example.

Most people probably wouldn’t argue that a game’s graphics and sound are

too good for its breadth and depth, but there are times that you feel that the developer’s wasted immersive engines on limited content.

Myst is arguably a good example, if you don’t love its type of puzzles. Eventually, we reach a point at which depth and immersion almost merge–where the graphics and sound are so good that they let you see, hear, and otherwise experience things that would otherwise have to be rendered as dialogue or written text–and that has implications for this thesis that I haven’t fully considered.

|

Fully half of Red Dead Redemption 2‘s game map exists mostly to look nice, with no significant gameplay content.

|

This thesis gelled as I play

The Seventh Link. If you haven’t been paying attention, developer Jeff Noyle paid a visit in the comments to

my last entry and offered some tips and maps, which motivated me to keep going with the title. The game is mechanically sound: Noyle did a good job replicating the basic experience of

Ultima III and

IV, including combat, while arguably improving the economy and inventory system. The problem is a reduction in content accompanied by an increase in size. Elira alone–let alone the three other planets–is as large as Britannia (from

Ultima IV), has almost as many towns and dungeons, and its towns and dungeons are larger. And yet in the entire game, there is less dialogue than a single Britannian town. While an

Ultima player has lots of side-quests and sub-quests to accomplish (find the mystics, find the runes, learn the words of power, meditate at shrines, etc.), the

Seventh Link player has a much simpler quest with fewer stages. In short, the game’s breadth far exceeds its depth.

When I last blogged about the game, I had explored a couple of dungeon levels but was worried about overextending myself. I think the developer intended a larger, stronger party before tackling the dungeons. Back on the surface, I soon encounter what I most needed: a pirate ship. After slaying the pirates in combat, I was able to board the ship.

|

| Blasting enemies with the ship’s cannon. |

As in Ultima III–V, the ship has cannons that can be used to mercilessly wipe out approaching enemies, but doing so offers no experience or gold. They’re best used to eliminate enemies you don’t want (e.g., anything that causes poison) so you can spend your hit points and spell points on easier and more lucrative prospects.

I used the boat to reach previously-inaccessible land areas and thus visit a few more towns. In one of them, I got a third character, a cleric named Tharon. One of the towns sold a “flying disk,” but it’s a bit above my price range. I need it to continue exploring the town, although I don’t know if you can take it with you when you leave.

|

| A second NPC joins the party. |

There are some interesting graphical vignettes in the outdoor area, including doors in the middle of mountain ranges, archipelagos connected by bridges, towns at the end of mazes, towns with lakes in the middle of them, and so on, but none of this interesting geography leads to any depth in gameplay. The towns have the same identical services and one or two lines each of useful dialogue. This makes the land somewhat exhausting to explore, which is why I’m now using the maps that Jeff provided with no shame.

|

| An interesting environment, and yet the town has no more depth or character than any other town. |

I’m going to make a push to win this in one or two more entries, before I get started with Star Control II, which will require a large devotion of time this weekend.

The final thing I’ll say about breadth, depth, and immersion is that my GIMLET doesn’t reflect them very well. The considerations aren’t entirely absent, but the GIMLET definitely rewards more of everything rather than good balance among the three axes. So far, it hasn’t been a huge problem, but I think it will become one as time marches on. Mediocre games from the 2000s will end up getting much higher scores than excellent classics just because they have more of everything–more NPCs, more character options, more history and lore, better graphics and sound, and so forth. I’m concerned that the GIMLET’s purely additive system will result in relative scores that I balk at, like Might and Magic IX ranked higher than Might and Magic III or a bore-fest like Kingdoms of Amalur outperforming Pool of Radiance.

I don’t have the answers to this conundrum yet, but sometime this year we’ll have a discussion about potential revisions to the GIMLET that better take these factors (and others) into account. This would be a good time to start organizing your arguments.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/02/breadth-depth-and-immersion-ft-seventh.html