From The CRPG Addict

|

| Character selection occurs right on the main title screen. |

Xoru

United States

Castle Technologies (developer and publisher)

Several versions released between 1987 and 1989 for DOS

Date Started: 13 June 2018

Date Ended: 5 March 2019

Total Hours: 7

Difficulty: Easy-Moderate (2/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at Time of Posting: (to come later)

Xoru has taken me on a hell of a ride over the last 9 months. Last June, I played it for a few hours, got stuck, and decided I had enough grounds to reject it as an RPG. Then, in December, I got a long, impassioned letter from a fan who begged me to reconsider. I fired it up again and got stuck in roughly the same place. This time, I put out a call for help and commenters Zenic Reverie (“

The RPG Consoler“) and D.P. got involved. They helped a bit but got stuck with the same puzzles that I did. Then I tracked down the author, Brian Sanders, and we exchanged several e-mails. Brian didn’t remember enough to help with my specific problem at first, but I must have put a bug in his ear, because a few weeks later wrote back with a map and hint guide that he’d “commissioned,” which suggests to me that I annoyed him so much that he paid someone to solve the game so I’d go away. On the same day he sent the hint guide, Zenic won it on his own and sent me his solution. In the end, I still don’t feel like it’s much of an RPG, but I’ll be damned if I’m not going to write about it after all

that.

|

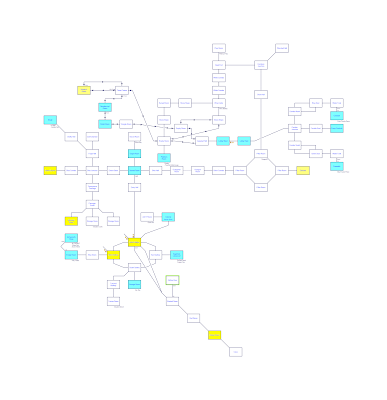

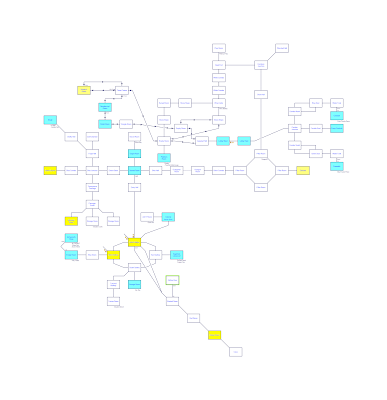

| My Trizbort map of the dungeon. |

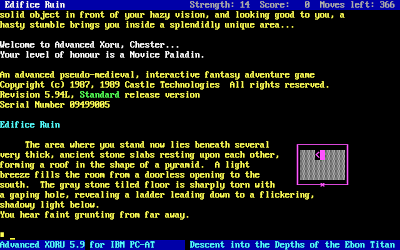

Written by San Diego-based developer Brian Sanders and released as shareware, Xoru is a text adventure-RPG hybrid that invites comparison with Beyond Zork (1987) in its mechanics, if not its attitude. The game went through several versions in the late 1980s and eventually acquired an “Advanced” tag (i.e., most sites have it as Advanced Xoru), but the main title didn’t change. There’s sort-of a subtitle–Descent into the Depths of the Ebon Titan–that appears far enough away from the main title that I’ve chosen to regard it more as flavor text than a true subtitle.

The backstory casts the character as a denizen of the modern world, abruptly wrenched by a cabal of wizards from a busy airport terminal, through a portal, and into a “pseudo-medieval fantasy world” in which he must explore a sprawling, multi-leveled dungeon for various reasons. In this, the game almost immediately clashes with its extremely brief character creation system in which you choose from among an unusual list of classes: paladin, necromancer, barbarian, zen-druid priest, and shadowy tracker. The implication is that each class will call upon special abilities and strengths to solve the game’s obstacles, in the manner Quest for Glory, but in practice it mostly means that some classes have an easier time in combat than others.

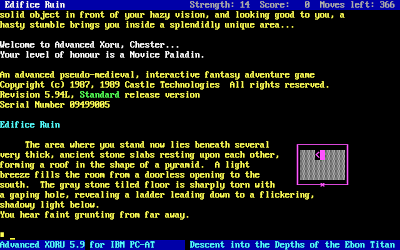

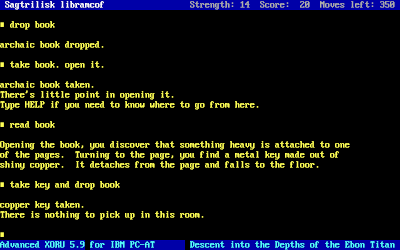

Gameplay for everyone begins in an “edifice ruin” at the top of the dungeon, each character finding items there appropriate to his class. The text window is accompanied by a mini-map that shows the directions the character can move, a clear Beyond Zork influence.

|

| The game begins. A little map tells you which ways you can go. |

The dungeon under the ruin consists of about 75 rooms arranged in three sections, logically-constructed and well-described. Xoru lacks most of Zork’s humor (which got a little too thick in Beyond, I thought) but it has the same attention to economical, vivid descriptions of rooms and events, at the best of times eliciting the sense of exploring a dangerous place with a good dungeon master. There isn’t much of a core “theme” to the dungeon, and like Zork the pseudo-medieval world has modern concepts like plumbing and elevators. Some examples of the experience:

- A trap door is on a high ceiling. You have to drag a bench from another room and stand on it to open the door. It takes you to an alchemist’s lab where you receive a couple of important items.

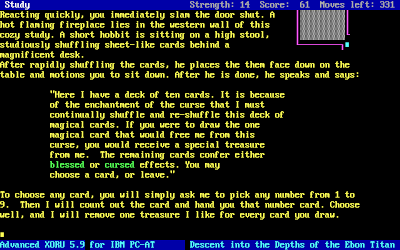

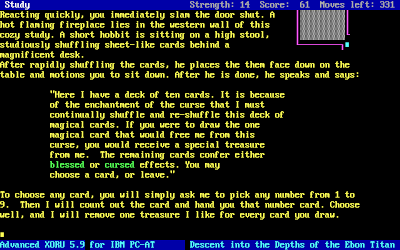

- A hobbit sits in a room with nine cards, kind of like a Deck of Many Things. He invites you to draw as many cards as you would like, one of which will free him. But for each draw, he will take a random item from your inventory. This can result in a “walking dead” situation if he takes an important item, so you have to prepare by dropping anything vital and loading up on miscellaneous treasure and extra weapons. The cards have various positive and negative effects. One of them does free the hobbit, for which he gives you a necessary gold key, and another gives you an important clue to another room.

|

| The memorable hobbit encounter. |

- The clue mentioned above is: “Make music with the giraffe, camel, elephant, and a pair of ferrets.” When you find a room with an organ, you therefore have to play GCEFF. The game has virtually no sound, but it does represent these tones faithfully. Playing the right sequence opens a secret door to an area with a vital key.

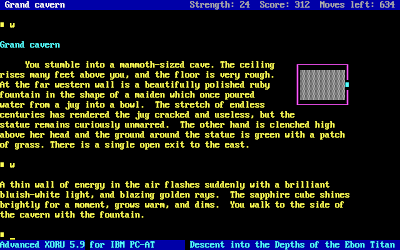

- An area has enormous tanks full of water. You have to go to a pumping station and turn the controls to empty the tanks, at which point you can enter each tank, each of which holds a different puzzle piece. Putting them together gives you a sapphire cube that you need for the penultimate area.

|

Was there a similar puzzle in one of the Zork games?

|

There are a fair number of “red herrings” in the game, not just as objects but also areas that feel like they ought to serve a larger purpose because of the detail in which they’re described (e.g., the torture chamber) or how much trouble it took to get there. For instance, there’s a puzzle involving an elevator that leads you to something called an “Ant-E-Room” where you have to kill a giant ant. But despite a vivid description of the room, there’s nothing to accomplish there. There’s an entire sub-section full of one-way chutes and passages that seems to have no purpose except to challenge your ability to get out if you’re unlucky enough to blunder in.

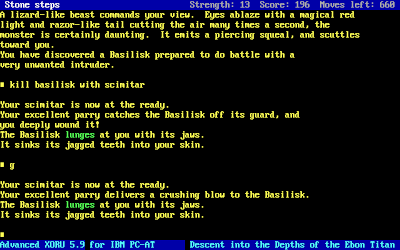

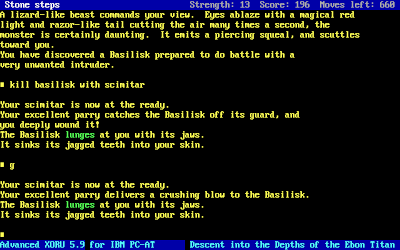

Monsters pop up occasionally–ogres, gnolls, ghouls, bugbears, basilisks, and maybe one or two others I didn’t write down. Fighting them is generally a matter of typing KILL [MONSTER] WITH [WEAPON] and letting the action play out. Spellcasters are supposed to find scrolls that they can use in combat by typing CAST and the name of the scroll. I never found any spell scrolls beyond the one that the game starts you with, which seems to do nothing. The game tracks an strength statistic and a health statistic that deplete as you take hits. The fighting classes seem to have a easier time than the others, but nobody has a terribly hard time. There are potions and generic scrolls scattered around the dungeon that increase strength and restore health and armor protects you from harm.

|

| Trading blows with a basilisk. |

|

I spent a lot of time annotating the presence of monsters and items on my original map, only to discover on a replay that these locations are heavily randomized for each new game. Sometimes you meet monsters in practically every room; other times, you can make it through the entire game without fighting once. Sometimes, I had half a dozen weapons to choose between; other times, I never let go of my starting scimitar. Most of the time, I never found any armor. Playing a couple of times helps you determine which items are necessary, as they’re always found in the same locations for every game. There are a lot of unnecessary items (except perhaps as fodder for the hobbit’s card game), including lots of gems and valuables, but also things that sound like they ought to do something, like ropes and 10-foot poles.

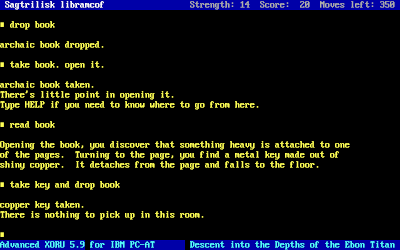

The interpreter is adequate. It follows most of Infocom’s standards; for instance, the player can switch between VERBOSE, BRIEF, and SUPERBRIEF descriptions of places he’s already been, and hitting G is a shortcut for “again,” or repeat the previous action. Z passes time. Yes, it’s derivative, but on the other hand it’s nice for players not to have to learn a new set of conventions. Unfortunately, the interpreter tends to fail when given complex commands or compound sentences with propositions. The manual says that it supports actions like TAKE THE APPLE AND EAT IT, but I found that most of the time it would do the first part of the sentence and ignore the second part. I’ve never seen the advantage to using such complex sentences anyway, so it mostly didn’t bother me. A little more annoying was the tendency of the interpreter to confuse objects; for instance, if you have both the sapphire and the sapphire cube, trying to drop the sapphire will actually cause you to drop the cube.

|

| The parser gets a bit confused from compound sentences. |

There are a ton of commands I never found any use for, including TALK, JUMP, KNOCK, PULL, PUSH, and LISTEN. These plus the extra items and poor use of the classes suggests to me that Sanders meant to keep expanding the game, or perhaps offer additional modules with the engine.

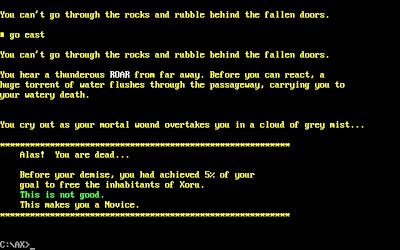

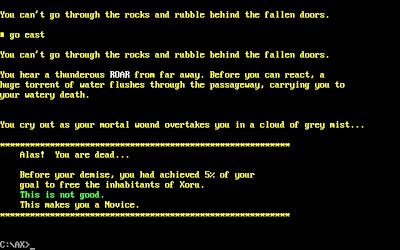

The game has a time limit of 360 moves, but that’s pretty generous, especially considering that a lot of moves don’t count, such as waiting. Also, for some reason, drinking water in a particular room (you have to solve an inventory puzzle involving a well bucket crank first) increases the number of available moves while also (nonsensically) increasing your score every time you drink. But if you do wait out all the turns, you suffer an instant death as water comes bursting through a couple of previously-unopenable doors and floods the dungeon. There’s also a hunger and thirst system, but food and water are both plentiful, and anyway you could easily win the game before even noticing that you’re hungry or thirsty.

|

| Instant death when you run out the timer. |

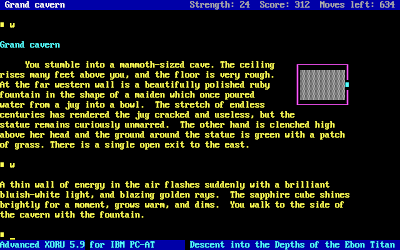

When I got stuck, was about 80% of the way through the game, and in retrospect, I wasn’t really stuck. I was overthinking a solution to a particular puzzle that involved replacing a cracked jug on a statue with a new one. I didn’t realize from the room description that the room is basically in two halves, and that to approach the statue, you need to walk through an energy barrier, which you can only do if you have a sapphire cube in your possession. There were times I had the cube, but I never tried walking through the room with the cube in my possession, I guess.

|

| The room where I spent way too much time trying to throw things at the jug, and poke it with poles, and lasso it with a rope . . |

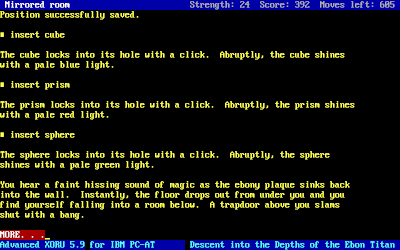

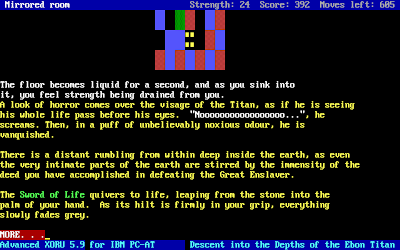

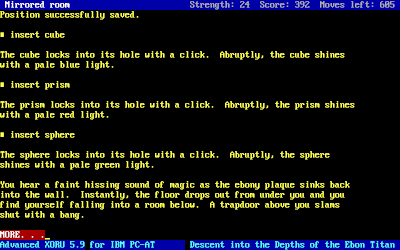

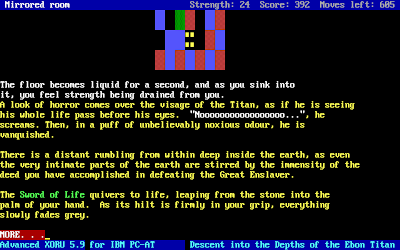

Once you solve this puzzle, you get a ruby prism, which reflects some laser beams coming out of the eyes of a couple of lion statues, allowing you to pass to the “Chamber of the Lake,” where you climb a statue and pry an emerald sphere out of one of its eyes. With sphere, cube, and prims in possession, you visit a room called the “Mirrored Room” and insert them in three appropriately-shaped holes. The floor drops out and you’re dumped into the final area, to confront the Ebon Titan.

|

| Reaching the endgame. |

This final area gives you an odd puzzle, a bit unsatisfying to me because I didn’t really figure it out. You find yourself on a grid of blue, green, red, and black (or “void”) squares, the colors shifting as you plot your moves. You’re represented as an asterisk, and the Ebon Titan is represented as an exclamation point. The only goal is to make it to the Titan’s square, but each of the colored squares (at least most of the time) has some kind of trap.

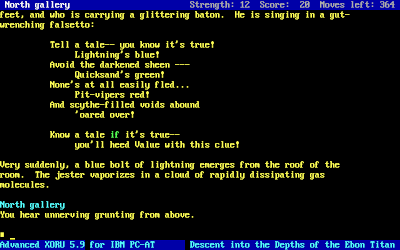

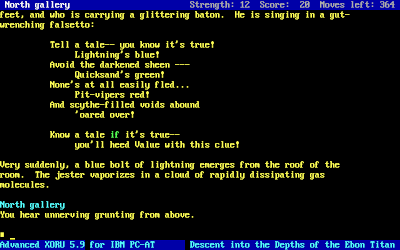

Earlier in the game, at a random location, a jester comes prancing through one of the rooms and gives you a clue about this area–just before he’s incinerated by a lightning bolt. The problem is that his clue (at least, to me) doesn’t really help because it indicates that any of the colored squares could have a trap.

|

| The jester tries to help but doesn’t tell me about any “safe” squares. |

It took me a couple of reloads, but I made it through by luck. I’d be really curious how I was supposed to deduce the right path here. Even the author of the hint file that Sanders commissioned wrote, “Look, I honestly don’t know where the traps are or what the colors mean. That is why you save.”

|

| Trying to make it through the final area. |

Once you reach the Titan’s square, he just dies with a pathetic “Nooooooooo . . .” The game congratulates you on having defeated “The Great Enslaver.” A sword that was embedded in the floor in front of the Titan–now named the Sword of Life–“quivers to life, leaping from the stone into the palm of your hand.” You’re teleported outside the dungeon, where the edifice collapses to reveal a gleaming diamond palace, and a wizard appears and congratulates you on becoming king. Not bad for a guy who was suffering from a flight delay just half an hour ago.

|

| Vanquishing the Ebon Titan. |

The game gives you a final score at the end which makes little sense. When I died, it said I had accomplished 100% of my goal, but when I beat the game having done all the same things, it said I was at 79%. Much like other text adventures, including Beyond Zork, once you know what you’re doing, a winning game is trivially short. You could win this one in 10 or 15 minutes.

|

| At 100%, I could have been a GOD. |

I’ll leave judgement as to its text adventure qualities to The Adventure Gamer, if they ever get to it. As an RPG, it barely qualifies. There is extremely minimal character development in the form of strength increases, and combat, simple as it is, does technically rely on attributes as well as equipment. In a GIMLET, I give it:

- 2 points for the game world. It’s not terribly thematic and could use a more compelling backstory. It would be nice to have heard something about the Ebon Titan and his status as an “enslaver” before actually meeting him.

- 1 point for character creation and development. There really is no point to the classes, particularly the thief-oriented “shadowy tracker.” It would have been cool if there had been class-oriented puzzles, for instance a door that a thief could pick, a barbarian could bash, and a magic user could open with a spell. Puzzles like the trap door could have easily been class-aspected rather than having everyone drag over a bench.

|

| Checking my inventory and stats. |

- 1 point for NPC interaction, and that’s very limited, consisting of basically the hobbit and a couple of optional encounters in random places with a jester and a hunter.

- 3 points for encounters and foes. The foes are unimaginative, and the puzzles are mostly simple inventory puzzles.

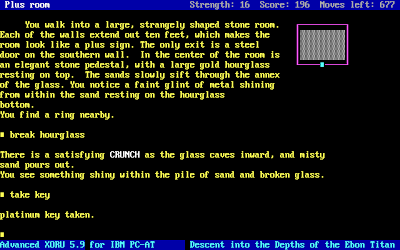

|

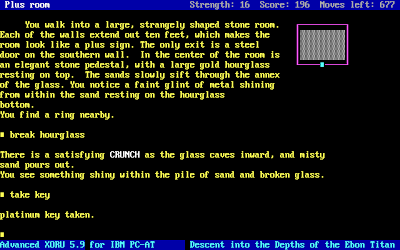

| At first, I thought there might be something more interesting to do with the hourglass, but no, the solution was to just BREAK it. |

- 1 point for magic and combat with no real options. I think maybe you can throw holy water at a ghoul, but otherwise your only “tactics” are KILL MONSTER WITH WEAPON.

- 2 points for equipment. There isn’t much in the traditional RPG style, and a lot of red herrings on the adventure side.

- 0 points for no economy. No, trading stuff to the hobbit doesn’t count.

- 2 points for the main quest.

- 2 points for graphics, sound, and interface. It gets most of this value for the quality of the text. The map images are mostly superfluous, the sound is extremely scant, and as we saw, the interpreter had some issues. I do like that you can move with the arrow keys instead of having to type NORTH and EAST all the time.

- 3 points for gameplay. I give it a little credit for some nonlinearity and replayability in the optional areas, although overall the dungeon is a bit too small and the puzzles (despite my getting stuck on one) are a bit too easy. It doesn’t drag, at least.

That gives us a final score of 17, which is pretty low, but I’m not really rating it in its appropriate genre. Text adventure fans will probably enjoy it more than RPG fans.

Xoru was reviewed in the April 1993 issue of Red Herring, where the reviewer said that he could “highly recommend it,” although he’d only been exposed to the demo copy, which killed you after 80 moves. The 1997 issue of the British magazine SynTax provided a more thorough review, agreeing with me that the “text descriptions are very good: not flowery but straight to the point and informative,” but complaining about the simple puzzles. He also notes–and I would have to agree–that the $44.95 price tag was a bit steep for a game of such limited content.

The version I played was 5.94. From the release notes, the Version 5 series had one more dungeon area than earlier editions, and at least some previous versions didn’t even bring the game to an ending. While this was the last text version, it wasn’t the last version entirely: In 2014, Sanders–his company revived and re-christened Castlelore Studio–created a 3D graphical version of the game for the Mac. You can see it in action

here and buy it

here. The graphics are what you’d expect from an indie developer (it’s “really hard to do by yourself,” Sanders wrote me), but as the video played, I found myself easily recognizing the various rooms based on the text versions that I’d explored. Certainly, I got zapped by those lion-lasers plenty of times.

|

| The series of “gallery” rooms represented in the 3D engine. |

In e-mail correspondence with me, Brian Sanders said that he originally wrote the game while he was a junior in high school. His mother suggested the title, but after he found it listed once-too-often at the bottom of game lists and the ends of catalogs, he made “Advanced” part of the title. It was originally just a grid of rooms with randomized monsters and treasure–something like a text Wizard’s Castle–but grew from there. Sanders says he was inspired by the Infocom titles as well as Choose Your Own Adventure books.

I was an avid reader and I was enchanted and captivated by these computer programs which made stories exploratory and interactive. There was this exciting illusion that the games offered limitless possibilities for exploration–even if the world was clearly finite, you had no way of knowing how far it went, and you would have to use your own mind to get there.

That’s a good summary of the experience playing a lot of RPGs, but perhaps specifically adventure games. With most RPGs of this era, and their fixed grids of tiles, you generally get a sense of the dimensions of the maps and overall game world, and you know when your character is about to hit its edges. There isn’t quite the same sense of wonder as to what’s around the next bend. Adventure games mostly feature non-symmetrical layouts that can sprawl unannounced in any direction. Once you have the entirety of the game before you, it often seems simple and underwhelming, but when you’re playing live and you don’t know whether the locked door opens into a closet or an entire sub-dungeon, it can be exciting in ways that perhaps my GIMLET doesn’t capture. I’m sorry we won’t be seeing many more of these.

Thanks to Brian, Zenic, and D.P. for helping to clear this one, and to everyone for your patience in a slow week as I recovered from a lot of travel and work late in February. The rest of this month ought to be back-on-track and productive.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/03/game-320-xoru-1989.html