From The CRPG Addict

|

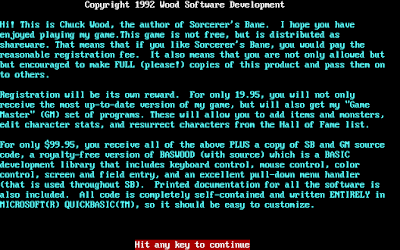

| Unfortunately, the game has no title screen. This is as close as we get. |

Sorcerer’s Bane

United States

Wood Software Development (developer and publisher)

Released in 1992 for DOS

Date Started: 27 January 2019

One of the things for which I am most grateful about this blog is that it introduced me to the roguelike sub-genre. The introduction was quite quick, as Rogue was the second game that I played. I had never encountered anything like it–had never encountered permadeath at all, really. The idea that you could invest dozens of hours into a character, and then he could be gone, just like that, with one wrong roll of the dice, is a hard concept to grasp when you’ve grown up playing RPGs that allow liberal saving and reloading. Even recently, when I was playing The Game of Dungeons, I had moments where my mind refused to believe that a character in which I’d heavily invested–hale and powerful only moments ago–was somehow suddenly irretrievable.

Because Rogue itself, with its permadeath and dungeon randomization, is so inherently replayable, games in the sub-genre really have to distinguish themselves with new content to be memorable. Otherwise, all you’ve made is a clone of Rogue. Thus, we find a lot more variance in roguelikes–more than I thought was possible before I experienced them–than we do in many other sub-genres. NetHack, UnReal World, Moria, and Wizard’s Lair I may look somewhat the same, but they took vastly different approaches in mechanics and content, making them all fun to play in their own way.

Along those lines,

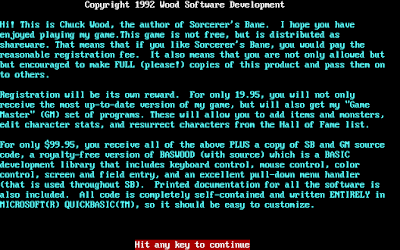

Sorcerer’s Bane is an admirable effort from Indianapolis-based developer Chuck Wood. (Wow, is that a difficult name to Google. I’m sure there’s at least one “Peter Piper” out there with the same problem.) If I’ve found the right man, he would have been 18 when the game was released as shareware. (He asked $19.95 for it, or $99.95 for a version with the source code.) While it has a youth’s sense of humor in some of the text, the game is competently-programmed and highly-original. Wood clearly played

Rogue (and perhaps

NetHack) and was familiar with

Dungeons and Dragons conventions, but he wasn’t overly restricted by them.

|

| Until you register, you have to see this message every time you quit. I’d happily pay the shareware fee, but I can’t track Chuck down. |

The backstory concerns two sorcerers named Lodi and Sabee who together founded a magicians’ academy called Mogadore. Each of the wizards wielded a Staff of Power. For some reason, Lodi turned evil and killed Sabee, hoping to use his Staff of Power in conjunction with his own to achieve near-omnipotence. For some reason, Lodi was unable to use the staff, so he broke it into four pieces and hid them in various parts of Mogadore, guarded by four dragons. Lodi them sequestered himself in the lowest levels of the (now-) dungeon to plot further mischief. The player’s mission is to reunite the four pieces of the staff, figure out how it works, and destroy Lodi.

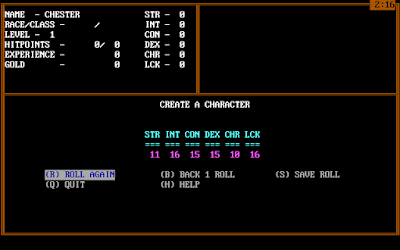

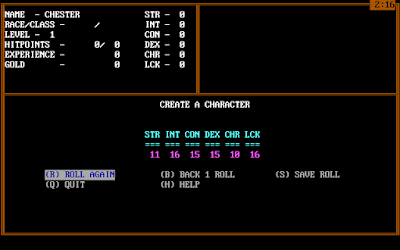

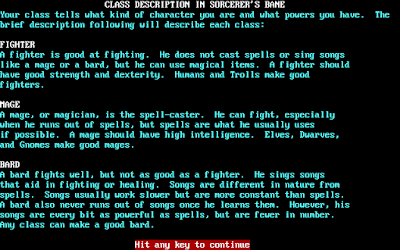

Character creation has the player roll for strength, intelligence, constitution, dexterity, charisma, and luck on an 8-18 scale. He then chooses from human, elf, troll, dwarf, and gnome races, which further modify the attributes. Classes are fighter, magic user, and bard, and each has unique talents that (unlike the typical roguelike) can’t be acquired by the other classes. In other words, no one but a magic user will ever cast spells, and no one but a bard will ever sing bard songs. I went with a gnome bard which is a little unusual for me.

|

| Creating a character. |

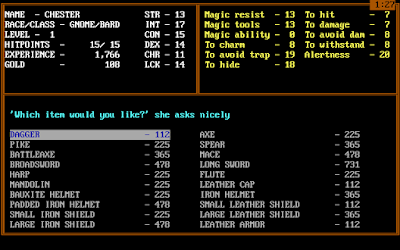

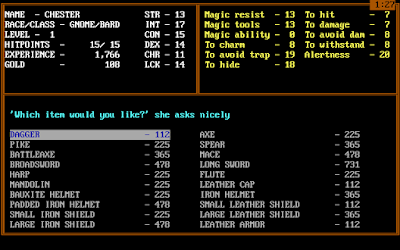

The game begins in a menu town with a single shop and a cleric. You don’t have much gold to start, but you can return to the menu level whenever you want. The shop buys and sells weapons and armor, identifies equipment, and recharges wands. The cleric heals, cures sickness, and removes cursed items.

|

| The store has the standard selection of equipment. |

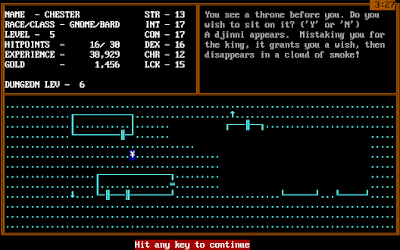

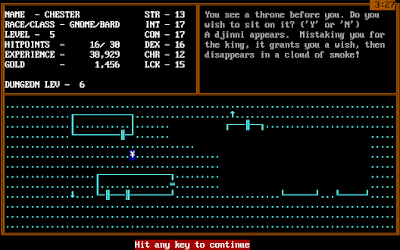

Below the menu town, each dungeon level is 12 x 76 squares, with features randomly generated. The levels don’t have twisting corridors of most roguelikes. Instead, most of the space is open, but with occasional buildings or “rooms.” The character is represented by a yen symbol (¥). As you move, you reveal the squares around you, which might contain traps, treasure, or special encounters. Combats appear randomly as you walk, in a separate interface, and monsters are not seen in the environment.

|

| Exploring one of the dungeon levels, I have a special encounter with a throne. |

My initial reactions to the game were negative, primarily because it has far fewer options than most roguelikes and thus seemed “dumbed down.” In the exploration window, there are no regular commands beyond movement and inventory. There’s no food system and no complex interaction between items, and no object permanence–when you drop things, they disappear entirely.

|

| A fairly small set of commands for a roguelike. |

Soon, however, the game’s strengths and innovations started to come through. Among them:

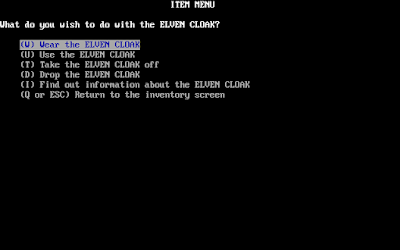

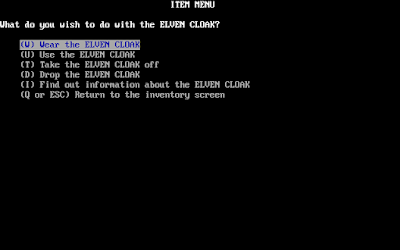

- It has an excellent interface–one of the best I’ve ever seen in any game. It supports both the mouse and keyboard, and also multiple ways to use the keyboard. For instance, you can arrow among the commands and hit ENTER or type the letter of the command. It anticipates multiple ways that different users might want to accomplish things. For instance, in the inventory screen, you can choose to (W)ield, (D)rop, or (I)dentify items (among other commands), or you can select the item first and then see a sub-menu of the different things you can do with it. It offers a few shortcuts; in combat, (K)ill causes the entire combat to play out as if you hit (F)ight every round.

|

| I could have done all these things from the previous inventory screen, or here in a way that’s specific to the elven cloak. And I can either press the appropriate key, arrow to my selection and hit ENTER, or use the mouse. |

- The “help” system is also excellent. Almost every screen has a (H)elp command that provides contextual assistance with your current situation.

|

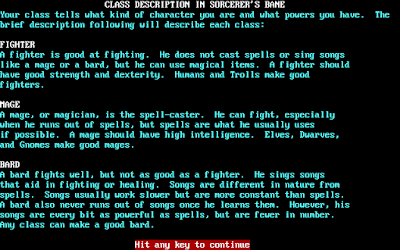

| Hitting “Help” on the class selection screen brings up a description of each class. |

- You get experience just for walking. Every step grants you one point. This makes it possible to play a “stealth” version of the game, at least at low levels.

- In combat, you can attempt to avoid battle by simply talking to the enemy. Results depend on charisma, but it works a lot of the time with animals and neutral creatures. There are even “good” creatures like dryads who have additional encounter options if you talk with them.

|

| What kind of monster wants to kill a dog? |

- After you’ve faced an enemy a few times, you can bring up a “Monster Info” screen the next time you encounter him. It tells you the monster’s statistics (with your own in comparison) and gives you a brief description.

|

| The game shows what I know about hobgoblins. |

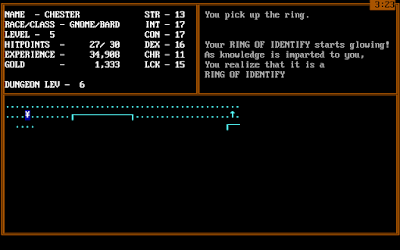

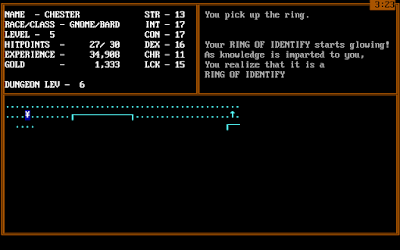

- I like the identification system. Items can be cursed or enchanted, and if you want to take a chance, wielding or wearing the item immediately tells you everything about it. You can pay to identify items in the shop, and you can find Rings of Identify that (usually) identify things automatically.

|

| Yo, dawg . . . |

- Items have fun effects (both advantageous and disadvantageous) that I’ve not seen in many other games. A “Book of Intense Wealth” gives you thousands of experience points or gold pieces. The cursed “Forward-Only Motion Boots” don’t let you use any up ladders. I’m not exactly sure what the “Attacking Floating Sword” does, but it’s apparently a good thing. Items otherwise offer the types of resistances and advantages that you’re used to in roguelikes, and of course you can keep multiple items to swap in and out of active inventory as the situation demands (e.g., putting on Ring of Disease Resistance when you meet a zombie).

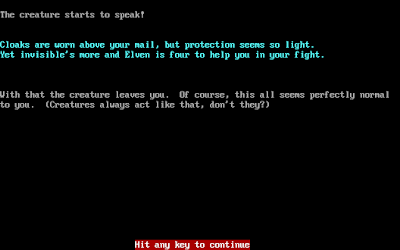

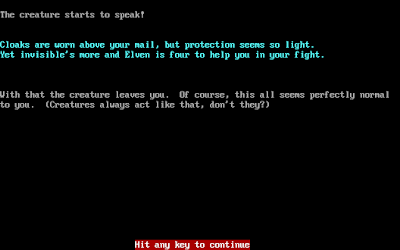

- There are interesting special encounters. Dryads give you hints. Gamblers offer you a chance to wager on a card game (and some of them carry Decks of Many Things). Thrones can convey a variety of benefits or demerits. Fountains usually heal (fully) but sometimes improve or reduce attributes instead. (Fountains and thrones, of course, are staples from earlier roguelikes.)

|

| A dryad offers some equipment advice. |

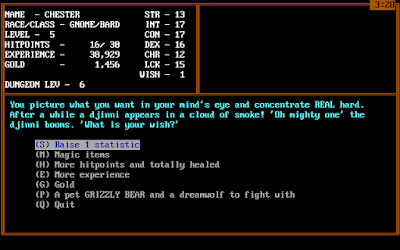

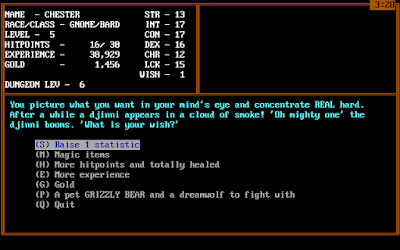

- There’s a complex “wish” system. Various items and creatures can grant you wishes, which accumulate in an associated statistic. When you want to use a wish, you just hit “W” and a menu comes up offering various options, including raising an attribute, gaining a magic item, healing, extra experience, gold, and “a pet grizzly bear and a dreamwolf to fight with.” I haven’t tried that last option yet.

|

| Some of the wish options. I only have one, so I guess I’d better save it. |

Monsters include the standard set of roguelike/fantasy creatures. On the first few levels, you might run into jackals, goblins, kobolds, hobgoblins, floating eyes, skeletons, and giant rats. Later, you get more advanced creatures with special attacks and defenses. Were-creatures can only be hit by magic weapons and can cause lycanthropy, for instance. Amorphous acids can corrode items. Mad dogs and zombies can cause disease. Thieves can steal your money pouch and disappear. After Level 10, there are spellcasting enemies like satyrs, gorgons, and wizards. I’ve found it best to run away from a lot of these creature types, especially the animal ones that never offer any gold or items after you kill them.

|

| Fighting a mad dog is a bad idea. They can disease you and offer nothing once you kill them. |

In combat, you have options to attack, talk, run, cast a spell (for magic-users), sing a song (for bards), make a wish, and use an inventory item. A lack of missile weapons and a low variety of items makes combat a bit less tactical than some roguelikes, but it’s not bad and at least it’s over fast.

Health does not regenerate on its own, but in consideration for that, and for permadeath, combat is relatively easy, at least for the first 8 levels or so. A lot of battles end with no hit point loss for the character at all. Running away works most of the time. Every few levels, you find a fountain that usually heals you, and both magic users and clerics have magical healing options. You also occasionally run into wandering clerics. And if you die, the game runs through a humorous scene in which the gods might resurrect you, but at a cost of all your gold (if you don’t have much, your chances of resurrection seem to be lower) or some inventory items.

|

| A silly scene that accompanies death. |

I have no idea how many levels the game offers, but I played this first session to dungeon Level 10. My character rose to Level 6 during the process, which each level increasing maximum hit points and improving a few behind-the-scenes statistics (which you can call up) like “magic resistance,” “to hit,” and “alertness.” Many of my attributes improved from potions, books, and fountains. On Levels 9 and 10, the game started to get a bit harder, with tougher enemies like gorgons and wizards, and matters weren’t helped by the fact that an unlucky use of the gambler’s Deck of Many Things caused me to lose my entire inventory.

|

| He did warn me. |

I’ve gained two bard songs during the course of the game. “Hypocrita” is a healing song and “Bazerker” is a combat song. Neither seemed to have any effect when I had a regular flute, but once i found a magic “Flying Flute,” they both started paying off. In particular, “Hypocrita” heals 6 hit points per move, which means that combats have become about individual difficulty rather than collective difficulty.

|

| My inventory before the unfortunate event above. |

I expected to find shortcuts to the surface the farther down I explored, but it hasn’t happened yet. That means if I want to go back to the shop, I have to climb up 10 dungeon levels. I guess after a certain point, you have to rely on your own resources for item identification and wandering clerics for healing that you can’t accomplish yourself. Since I lost all my stuff, though, I guess I’m going to try to make it back to the surface to buy a new set of equipment, then perhaps grind a bit on lower levels until I find a few magic items again (magic items are most common in treasure chests, but monsters occasionally drop them). If I lose this character entirely, I’ll probably restart as a magic-user so I can experience that side of the game, but I’ll likely backup my character every couple of levels.

Sorcerer’s Bane will end on a high note if it doesn’t last much more than another four or five hours. Character development caps at Level 15, which suggests I’m about 40% of the way through, although it concerns me that I haven’t found any of the dragons yet. Maybe they’re all grouped together on one lower level. For now, the game hasn’t made any major mistakes, and I’m impressed that the young developer showed so much innovation and sense of balance.

Time so far: 4 hours

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2019/02/game-317-sorcerers-bane-1992.html