From The CRPG Addict

MicroProse (developer and publisher, under its Microplay label)

Challenge of the Five Realms is a plot-heavy axonometric title set on the flat world of Nhagardia. A prince must race against a creeping darkness to retrieve the five crowns of Nhagardia’s five kingdoms (human, gnome, elf, fish-man, and effete flying man), whose leaders have been killed by the mysterious, demonic Grimnoth. The game is as full-featured as anything in 1992, with animated cut scenes and voiced digital dialogue at the beginning and end. There are hundreds of NPCs, dozens of side quests, and a book’s worth of dialogue. Many of the NPCs may join the party, which maxes at 10. The tactical combat system works relatively well. But the game lacks in other key role-playing areas, particularly character development.

*****

There are a few other flaws that don’t entirely cripple the game but come close. The time limit is employed badly. The limit itself is fairly generous, and it’s hard to imagine a moderately conscientious player running afoul of it. The problem is that the “creeping darkness” slowly eats the map from the bottom up, so that your time constraints are a lot more urgent for the locations in the south The various towns and castles in Nhagardia are all interesting in appearance and character, and it’s a shame to have to rush through them. It’s equally a shame to reduce replayability by forcing the player to prioritize the southern locations; without the “creeping darkness,” the game would be satisfyingly non-linear.

|

| What happens if you miss the time limit. |

I have a feeling that this is going to GIMLET in the extremes, with several high scores and several low scores.

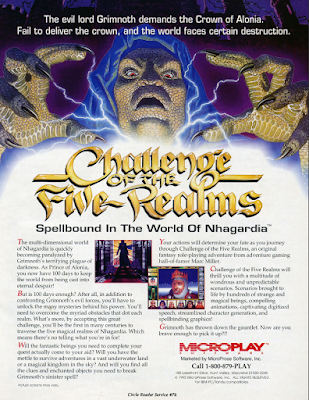

1. Game World. The setting, backstory, and plot are all strong. I like the way that each kingdom has its own character, and the people have their own values. In the human kingdom, each town and castle has its own story to impart. I love the slow reveal of the depth of Clesodor’s evil. The twists at the end didn’t do as much for me, but at least they brought the whole thing to a proper conclusion. Someone really wrote this one. Score: 7.

|

| Grimnoth lays out the charges against my father. All of this was unknown at the beginning of the game. |

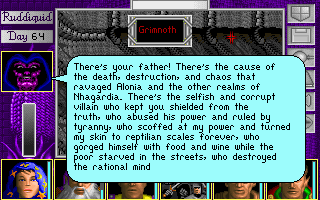

2. Character Creation and Development. If the old Paragon develops should have kept anything from their GDW experience, it was the Traveller-style character creation process that puts the character through a wringer of training and experience before shoving him out the door and into your party. Instead, the authors opted for an Ultima IV-style process of answering role-playing questions to determine the main character’s starting skills and attributes. Other characters come as they are.

Unfortunately, where the creators’ GDW experience comes through the most is in the lack of character development. No explanation is given for why some skills (“Learn Spells,” “Bargaining”) increase steadily with use while others (including all the combat skills) don’t increase at all. It is a depressing oversight that nearly strips the game of its RPG credentials entirely. Score: 2.

|

| Chesotor ended the game hardly better than where he started. |

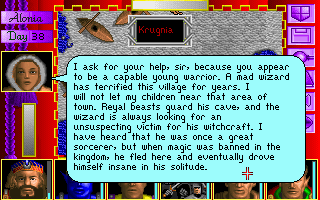

3. NPCs. Challenge undoubtedly offers more NPC speech than any previous game. It isn’t quite “dialogue,” though. Except for a small number of yes/no responses, the game speaks for the characters, and thus the NPCs’ speeches are more like information dumps than anything approaching “role-playing.” Beyond that, the attention to NPC characterization is excellent, as is the general quality of the text.

Even more fun is the sheer number of NPCs who will join your quest. You have a generous party size (10) and at least three times that number of potential members, including the novel idea of “grouped” party members. For the first time that I remember in RPG history, your NPC companion have bits of banter as you enter areas, talk to other NPCs, and solve quests. My only complaint is that dismissed companions utterly disappear from the game instead of going back to where you acquired them (or to a central location). Score: 6.

|

| The NPCs in this game were interesting, but man did they have a lot to say. |

4. Encounters and Foes. Weak again. Almost all of the combat foes are people, with very little to distinguish them or to change player tactics. There are no puzzles beyond simple inventory puzzles. However, the game does excel in what I call “contextual encounters.” Nhagardia is not a land swarming with monsters that you must mindlessly kill; every combat is set in a context, usually with some preceding dialogue, so you always know who you’re fighting and why. Score: 3.

5. Magic and Combat. Ironically, the old Paragon team finally fielded a decent combat system in a game that only has about a dozen battles. It’s hard to characterize the exact nature of the system. It looks somewhat like “real-time with pause” except that it only appears “real-time” and there are actually turns at fixed intervals behind the scenes. Either way, whether the player micromanages the combat by issuing new orders every round or just relies on “quick combat,” the mechanics and tactics are generally satisfying.

Spells are another matter. The spell system is primarily used for puzzle-solving (woe is the character who lacks “Truth,” in particular) and travel. Combat spells are a bit under-developed. There are no area-effect spells and only a couple of buffing spells. Magic depletes so quickly that you can only cast a few spells in any given combat anyway, which makes it jarring to have so many endgame enemies that don’t respond to physical weapons. Again, the developers’ lack of experience (none of the GDW properties were fantasy RPGs) shows here. Score: 4.

|

| Fighting some peregrines. |

6. Equipment. Another weak area. The game has slots for a lot of different equipment types, but I only ever found a few rings, one item of headwear, and a couple of pairs of boots. There are maybe three magic items to find during your adventures, but beyond that the roster of weapons and armor is no different than the starting store in a typical D&D-derived game. Score: 2.

7. Economy. The economy is so favorable to the player that I think it might be bugged. From the moment the game began, I spent blithely whenever anyone asked for money, and I never seemed to lack any. Of course, there isn’t a lot to spend money on. All shops of the same type sell the same things, and you can get most of your equipment in the starting castle. Score: 2.

8. Quests. If you can say one thing for the Paragon team, they’re one of the only groups of developers in this period that truly understands “side quests.” Every map area has a bunch of Joe Commoners with their own problems that they’re hoping that the characters will solve. These side quests are rewarded with gold, spell reagents, equipment, and the availability of new NPCs. Some of the quests even have multiple options for ending them, usually favoring one town faction over another.

Meanwhile, the main quest and its various stages are equally compelling. An open question is whether it would be possible to complete the game by murdering each king for his crown. Score: 6.

9. Graphics, Sound, and Interface. The graphics are very good for the era, and I particularly like the title cards that precede each map. Sound effects, on the other hand, are a bit too sparse. There are no background sounds, and only the occasional effect during combat.

The interface is horrid. Keyboard backups for the most common commands don’t help much when you have to move exclusively with the mouse. The process of hailing and talking to NPCs is needlessly complex and inconsistent. After 35 hours, I still can’t give a good account of it. Sometimes, you have to both “Hail” and “Speak” and other times you just seem to have to walk near an NPC to get him to start talking. Sometimes, the speech cursor remains active and you can keep clicking on other NPCs, and sometimes you have to start over. Sometimes dialogue exits on its own and sometimes there seems to be no way to exit. Once or twice, I literally had to reload the game.

|

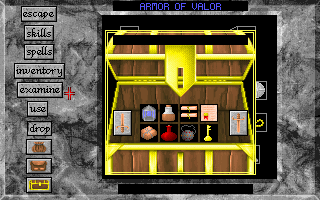

| The multiple inventory screens added needless complexity to what should have been a simple process. |

The inventory interface is also needlessly cumbersome. The idea of a single chest shared by all characters is great. Beyond that, each character simply needed an individual “wearable” inventory. Instead, each character has his own pouch, backpack, and non-specific “inventory” space in addition to the wearable inventory and collective chest. Also, the process of removing and replacing things in the chest could have been quicker. The interface issues were so consistently annoying that they weaken the entire category score despite the good graphics. Score: 2.

10. Gameplay. As previously discussed, the game would be wonderfully non-linear if the team hadn’t forced the player to prioritize the southern locations. Even with that weakness, there’s still a lot of non-linearity to the game, which enhances its replayability. The length and challenge are about right. We thus finish on a strong category with only minor complaints. Score: 7.

The final score thus adds up to 41, well above the “recommended” threshold. I thought it would out-perform all of the Paragon games, but it turns out I gave the same score to MegaTraveller 2, which had many of the same strengths and weaknesses.

There must have been something in the water that month, because Dragon magazine’s three-star pan is equally baffling in different ways. The author’s enjoyment is far too influenced by what he or she sees as plot holes (“Why the evil fellow simply can’t take the crown after he kills the king makes no sense”), as if any fantasy RPG of the period holds up to the most cursory plot scrutiny.

As we previously covered, Challenge was the first RPG from the old Paragon Software team after the company was acquired my MicroProse. The team included Marc Miller, F. J. Lennon, Paul M. Conklin, and Quinno Martin. For some members, this was their last RPG. Others contributed to MicroProse’s BloodNet (1993), which uses a similar interface, before leaving MicroProse for Take-Two Interactive. BloodNet will be our last MicroProse title and the last of the Paragon legacy. Hopefully, by then I’ll have been able to get in touch with one of the team’s principal developers and get some insight as to why this series, though innovative, always slightly missed the mark.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/challenge-of-five-realms-summary-and.html