From The CRPG Addict

Independently written and released on university PLATO system in 1982

Date Started: 20 April 2019

The last of the PLATO RPGs, Joshua Tabin’s Camelot united the two previous traditions present on the terminal-mainframe system. From the Dungeon/Game of Dungeons/Orthanc line, he took the single-player approach using a multi-classed character. From the Moria/Oubliette/Avatar line, he took first-person dungeon exploration (with a menu town on top) and a combat system where you fight “stacks” of multiple monsters. Players control individual characters but can message each other as they explore the same shared dungeon, which resets on the hour or whenever all the rooms of a level are cleared. The ultimate goal is to get strong enough to explore Level 10, get Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, and use it to force Lucifer to cough up the Holy Grail. It takes a while to learn the game’s features, and it’s pretty hard even with its “relaxed permadeath” approach, but it has an addicting approach to leveling and inventory acquisition

*****

I’ve often wondered how I would have fared if I had been a student at one of the PLATO universities in the 1970s or early 1980s, and now I have my answer: my life would have been ruined. I would have skipped classes, missed deadlines, plagiarized papers–anything to spend more time on the computer. I know because that’s basically what I did this week. I procrastinated on an already-overdue report to win this 40-year-old game. The fact that money, and not just a grade, is riding on this report probably makes it worse.

Like all of the PLATO games, Camelot is about mechanics. It hardly has any story at all. Its allure comes from its constant sense of character development–the idea that the next level, the next epic item, the next 10,000 points (putting you one position higher on the leaderboard) are all just around the corner. This is the kind of game that transitions you from 1:00 AM to 4:00 AM before you’ve noticed what happened.

I don’t often schedule my games to offer compelling comparisons, but what an amazing lesson in contrast we have between Camelot and Challenge of the Five Realms, written 10 years apart for very different audiences. Challenge has all of the content of an excellent RPG–game world, NPCs, dialogue, and plot. Camelot has the mechanics of an excellent RPG–statistics, inventory, and combat tactics. I think it’s fair to say that I appreciate and enjoy Challenge‘s approach, but I am addicted to Camelot‘s.

Part of the fun of my experience came from author Josh Tabin’s occasional presence as I played. (He and his son stayed up with me until 1:00 AM the other night, cheering me on as I won.) I couldn’t experience the game the way it was with 20 players swarming the dungeon, but at least I got some of the experience. He helped me fight a few tough battles (the game divides the treasure among the number of people in the room, I discovered, even if you can’t see each other) and alerted me where he’d seen a particular foe or item. I want to say that he gave me a lot of hints, but perhaps a better way to say it is that he led me to a lot of hints. He avoided most outright spoilers and instead said things like “Hey, I saw a TARDIS in the shop–you should buy it and see what it does.”

Unfortunately, players can’t directly help each other by giving each other money or equipment. But they can alert each other to where they’ve seen, say, a group of lizard men with a particularly large chest, knowing that lizard men often drop magic boots. They can say stuff to each other like, “I just sold a Manual of Quickness to the store if anyone wants to buy it.” And of course they can help each other directly in combat.

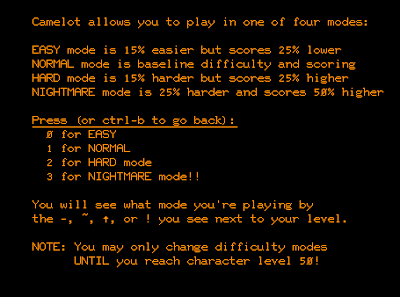

I think it’s been a while since Tabin had anyone take such active interest in his game. He used the occasion to make some tweaks while my own experience was in progress. One was to add a “difficulty setting.” He said the programming was already in there, but he had never turned it on. Now any player can customize his own difficulty from “easy” to “nightmare.” Easier games make enemies less effective but also give you a lower score. “Nightmare” lets you build your character fast for some extra risk. He also added a few more trap types and introduced a system by which low-level enemies run away from high-level characters. I’d often wondered why some of my charmed companions would up and ditch me for no reason, and it turns out that they do it when you attack other enemies of the same type. In a recent update, he made that explicit by having the companion say “he was my BROTHER!” as he leaves your service.

|

| The author added a difficulty setting during the middle of my session. |

In my previous entries, I talked a lot about the game’s difficulty. It is perhaps most accurate to say that like a good roguelike (which Camelot does an excellent job anticipating), it is very difficult until you get a lot of experience and get a natural feel for what’s going on. I was well into my 40th hour before combat tactics really “clicked,” and I started to learn instinctively when to use spells, when to attack, and when to run. It took a while before I got to the point that I always had my hands on the right keys as I entered a room, allowing me to act before the enemy. I died a couple dozen times in the first 30 hours of the game and only half a dozen in the last 30.

Another important insight was learning how to strategically develop inventory. Each item has a label (the game calls it a “table”) from 1-12 associated with it, and these levels are highly calibrated with the monster levels. A mithril sword (Table 3) simply isn’t going to do much against a red dragon (Table 8) no matter how high your level or attributes. So instead of blundering all of the dungeon hoping to find anything, you prioritize trying to upgrade your lowest-level items. The average “table” of a looted piece of equipment is the same as the dungeon level on which you find it. So let’s say that most of your stuff is Table 7, but you’re still stuck with Table 4 armor (Frosty Plate Mail). Hopefully, you’ve noticed that dragons tend to drop armor, so you want to be on dungeon Level 7 looking for a Table 7 dragon (blue dragon) carrying Tale 7 Azure Plate Mail. If you’ve mapped carefully, you’ve noted that dragons tend to show up in rooms with scorch marks on the walls, and you thus head for that room on Level 7. No luck? Wait for the hour to roll around and the dungeon to reset, or reset it yourself with a TARDIS.

|

| Running into a high-level enemy with a high-level chest in a “stud room,” I use my Scroll of Identification to check the odds. |

I had originally thought that a lot of the dungeon room messages were just flavor text, but they actually alert you to the type of enemy you’re most likely to find there. Monsters of the “slime” table (green slimes, yellow molds, ochre jellies, black puddings) are usually found in rooms that say “the ground is very soft here.” If you want to avoid slimes, you avoid those rooms. If you’re trying to find enemies from the “bad cleric” list and the potions and scrolls that they often carry, you look for rooms described with “crosses and an altar.” Thieves are in rooms with “empty wallets” on the floor. The specific composition of the rooms resets on the hour, but the locations of the rooms of each description do not.

The dungeon levels are full of the types of navigational obstacles that you’ve experienced if you’ve played any first-person wireframe game. These include spinners, pit traps, one-way chutes, and teleporters. Some of these are necessary to navigate the dungeon, and you have to map carefully. For instance, you can take regular stairs all the way to Level 6, but to get to Level 7, you need to take a teleporter behind a hidden door on Level 3. Level 8 can only be reached via a teleporter from Level 5, which is in a section that can only be reached via a teleporter on Level 7. Despite the complexity, you learn the steps pretty fast, and I found I could make it from the town on Level 1 to Level 10 in about 3 minutes–faster, of course, if I had the rare Wand of Teleportation.

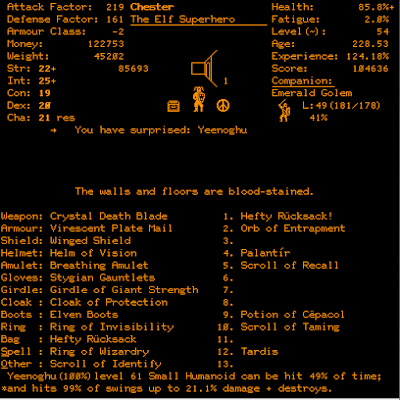

As you explore downward, it’s a good rule of thumb to make sure that either your weapon or your spell item is one or two levels higher than the current level you’re exploring. You can do this by repeatedly attacking each level’s “stud room”–cued with a note that the walls are covered in blood–which reliably offers monsters and items 1-2 levels higher than the level’s average. So if you defeat the stud room on Level 6, there’s a decent chance you’ll find a Table 8 item.

I was lucky to get a Ring of Wizardry (Table 9) at the stud room on Level 7, and it let me blast my way through the rest of Level 7 and Level 8. (Downside: every time you use a spell item, there’s a chance it will run out of charges, and re-charging it at the store is expensive.) Then, early in my Level 10 explorations, I ran into a “friendly” Asmodeus and bribed him $140,000 to drop his chest and leave the room. It had the Level 12 Ruby Staff of Asmodeus in it, which let me kill most things on the level.

Leveling is pretty constant during this process, but it caps at Level 60. I don’t like level caps, but in this case I think most players would be hard pressed to hit the level cap long before the end of the game.

|

| My map of Level 10. The numbers are all teleporters. |

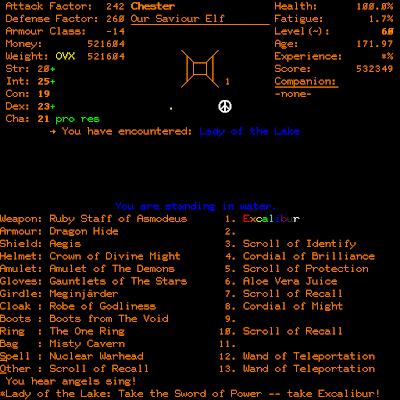

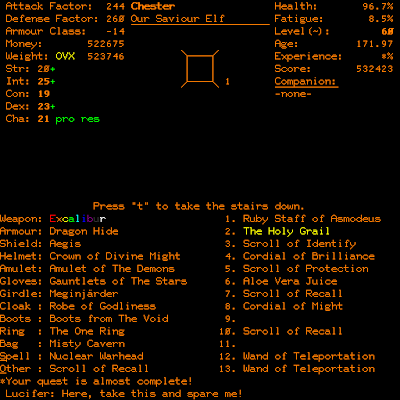

Level 10 has the game’s final encounters with Lucifer and the Lady of the Lake. Lucifer has the Holy Grail but kills you instantly if you don’t have Excalibur. The Lady of the Lake, meanwhile, won’t give you Excalibur unless you’re fully outfitted with Table 12 gear. How do you get Table 12 items when there are only 10 dungeon levels? You can get extraordinarily luck, as I did with Asmodeus, or you can camp out at the Level 10 stud room, which will feature a new Table 12 enemy every hour on the hour. The Table 12 enemies are a rogue’s gallery of pop culture references: Asmodeus, Tiamat, Zeus, Poseidon, The Evil One, beholders, Thor, Jubilex, Lolth, Saruman, Sauron, the Master of Shadows, and–at the top of the “bad clerics” list–Jerry Falwell.

|

| Finding a Level 12 artifact. |

There’s no guarantee that these enemies will always drop Level 12 artifacts. And if they do, there’s no guarantee you won’t accidentally destroy them by fumbling the trap. So you have to churn through dozens of encounters to assemble your list. If you don’t want this to take dozens of hours, you have to load up on TARDISes (which reset the dungeon manually) and keep using them. This took me about 6 hours by itself and would have taken longer if Tabin hadn’t sold one of his character’s extra TARDISes to the store.

When you finally have a complete set of Level 12 gear, you go to a water room at the bottom of Level 10, and the Lady of the Lake hands over Excalibur.

|

| Yes, everybody knows it’s no basis for a system of government. Please let it go. |

From there, it’s just a few steps to the stairway to HELL, where you meet Lucifer. He cowers the moment he sees Excalibur, hands over the Holy Grail, and flees.

|

| Satan flees and hands over the Holy Grail. |

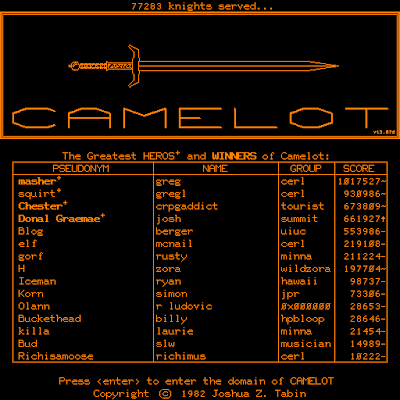

Once you have the Holy Grail, you need only return to the town, where the game gives you the option to retire permanently. If you want, you can keep playing and finding more treasure to increase your score, which affects your position on the leaderboard. I retired with a score of 673,809. That was enough to put me at the third spot on the board, behind two characters fielded by the mysterious “greg” or “gregl.” I could have beaten his high score, but it would have taken another 6 hours of gameplay, roughly.

|

| Am I ever. |

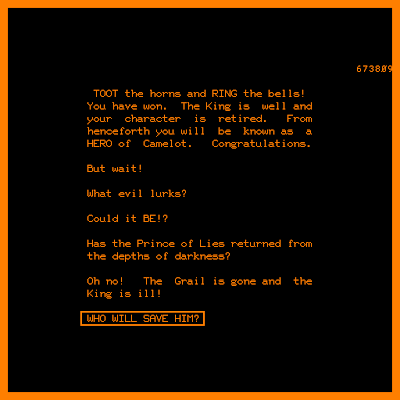

When you retire the character permanently, you get the following endgame text, suggesting a never-ending cycle of grail-finding. Then again, there has to be a rationale for more than one winner.

In a GIMLET, Camelot earns:

- 0 points for the game world. I thought about giving it 1, but I couldn’t even justify that. Despite its name and the presence of the Lady of the Lake (nonsensically on the bottom of a dungeon), the game doesn’t make any use of Arthurian themes, nor does it replace or supplement them with any story or sense of place. This was the norm with the PLATO series.

- 4 points for character creation and development. There are a few choices in character creation–particularly the race–which make a big difference during gameplay. I chose to take the elf, a weak character who has a low risk of dying of old age (he ended the game about 30 years younger than he started, thanks to Potions of Youth). During the game, leveling is continually rewarding even though it doesn’t give you any choices. The little sub-quests to kill specific monsters to reach some levels was a fun addition.

|

| I just turned Level 60. I assess the level of my equipment as the game gives me my next mission. |

- 3 points for NPC interaction. Okay, there are no NPCs. But for past PLATO games, I gave a couple points here for the PC interaction that accompanies those titles, and I like how it works here. You don’t need other players to enjoy the game, but they can enhance your experience. I also gave a point here to the ability to charm monsters to joining your little “party.”

- 4 points for encounters and foes. The game’s long list of monsters may be derivative, but Tabin did an excellent job programming their various strengths and weaknesses. A player has to balance his desire for treasure with the knowledge that thieves can steal treasure and slimes can destroy it. A careful player has to note what enemies cause sleep, paralysis, petrification, and destruction. The best part is that all of these strengths and weaknesses are determinable with a Scroll of Identification.

- 4 points for magic and combat. The game has a nice set of options for dealing with creatures, including spells, physical assaults of different types (trading accuracy for power), popping in and out of rooms until you “surprise” the enemies, hitting and running, stealing their treasure out from under them, and bribing them to go away. Only the spell system is underdeveloped, with the character only having access to one “spell” (more of an inventory item) at a time.

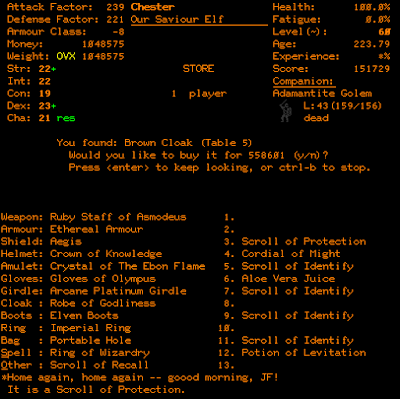

- 6 points for equipment, one of the best parts of the game. The player has 15 equipment slots with 12 levels of items for each slot. Even better is the wide variety of equipment that works in the “Other” slot–scrolls, wands, potions, and the like. There are manuals that permanently improve attributes, cordials that temporarily improve them, scrolls and wands that make navigation easier, items that charm different types of enemies (figuring out what works on which type is a mini-game in itself). Particularly well done is the Scroll of Identification. You can use it at any time, including in-combat and when in the middle of pulling items from a chest. Use it on a monster, and it tells you his hit percentages, damages, and special abilities. Use it on an item, and it tells you what it is and whether it’s cursed. Use it on an unopened chest, and it tells you what trap you’re facing.

|

| The store always held a chaotic selection of items. |

- 6 points for the economy. For most of the game, you’re trying to make enough money just to level up, so deciding whether to sell a potentially useful item for some extra cash, or whether to splurge on that item in the store, or whether to bribe a particular enemy (who may have more gold than the bribe in his chest) presents a continual set of decisions. Even late in the game, when you have plenty (especially after you hit the level cap), finding money contributes to your score.

- 3 points for quests. There’s only one main quest with no decisions or role-playing options, but there are also sub-quests throughout to kill specific monsters.

- 3 points for graphics, sound, and interface. The graphics are what they are, although I think the monster portraits are well done. There’s no sound. The keyboard interface for me was easy to master (and the game usually shows you all available commands at the current moment), and I like how everything is always laid out on the main screen, even if it makes the exploration window a bit small.

- 3 points for gameplay. This is from a 2020 perspective, of course, where I could have fit three other games in the time it took me to win Camelot. There were a lot of moments of frustration, and the linear nature of the dungeon reduces replayability even as the character options (and ever-present leaderboard) increases it. What feels to me today too long, with too many moments of frustration, would have felt the opposite on a college campus in 1982, with plenty of friends around to compare experiences and jockey for high scores.

The final score is 36, which crosses my “recommended” threshold, but not by so much that it would be absurd. It is notably the highest score I’ve given to a PLATO title.

What’s particularly amazing is that Josh Tabin wasn’t even a college student when he wrote Camelot–he was 12! As a member of the Explorer Scouts, he had access to a special program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (where PLATO was born) that taught middle- and high-school aged kids how to write code. Tabin explicitly joined the program because he wanted to play Oubliette (1978) and Avatar (1979) on the PLATO system. Somehow, he found time to complete Camelot in 18 months. Years later, he attended the university as a student and kept adding to the program.

It’s an extremely mature game, and the age of the programmer doesn’t come through at all except in a few bits of juvenile humor (in addition to “poison dart,” there is a type of trap that rhymes with it; one of the magic bags is called a “large hairy sack”) and the varied but predictable pop culture references. The game mixes the monster list from Dungeons and Dragons with the TARDIS from Doctor Who and the occasional quote from Blade Runner or monster or item from Lord of the Rings.

(Tabin waited a long time for this review. He first contacted me in 2013, and I assured him I’d play the game eventually. Somehow it disappeared from my master list, so he contacted me again in late 2017 to ask what had happened. I apologized and promised again that I’d get to it “soon.” In anticipation, he sent me a long, enormously valuable set of instructions. Then, it wasn’t until July 2018 that I took an initial look at the game and sent back some questions, then April of 2019 before I fully engaged it.)

I’m one of only four wins in 15 years (since the PLATO system was ported to Cyber1), but there were 43 winners between 1985 (when Tabin started keeping track) and 2003, including an early 2000s war between two users who went by the names “kappes m” and “pilcher,” each of them winning about a dozen times, trying to push each other off the leaderboard, and changing their character names to poke fun at each other. “kappes m” was responsible for a 20-hour speedrun in which he managed to get the Grail at character level 30 using a challenging pixie character, basically exploiting the pixie’s high dexterity to run dungeon levels that should have been out of his league and to steal high-level items from creatures that would normally have been able to stomp him.

But I’m the only one to have documented the ending, which is good enough for me. And with this, we have finally played the last of the PLATO games. I won’t be returning to the setting unless I go insane and decide to try to win Oubliette or Avatar or record some video of the games I’ve already won. It’s been a fun ride seeing the complexity that these amateur games achieved in the pre-commercial era, and Camelot was a fitting capstone to the series. But now I’ve got to stop procrastinating and work on that report.

Original URL: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2020/01/camelot-won-with-summary-and-rating.html